The Iron Brigade was one of the most renowned and celebrated infantry brigades in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. It consisted of four regiments, the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiments and the 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, with the 24th Michigan Volunteer Infantry added later. The Iron Brigade earned its name for its tenacity and unflinching courage in battle. Composed of men from the Midwest, the brigade was famous for the black felt Hardee hats that were worn by all its members, which helped distinguish them from other units in the Union Army.

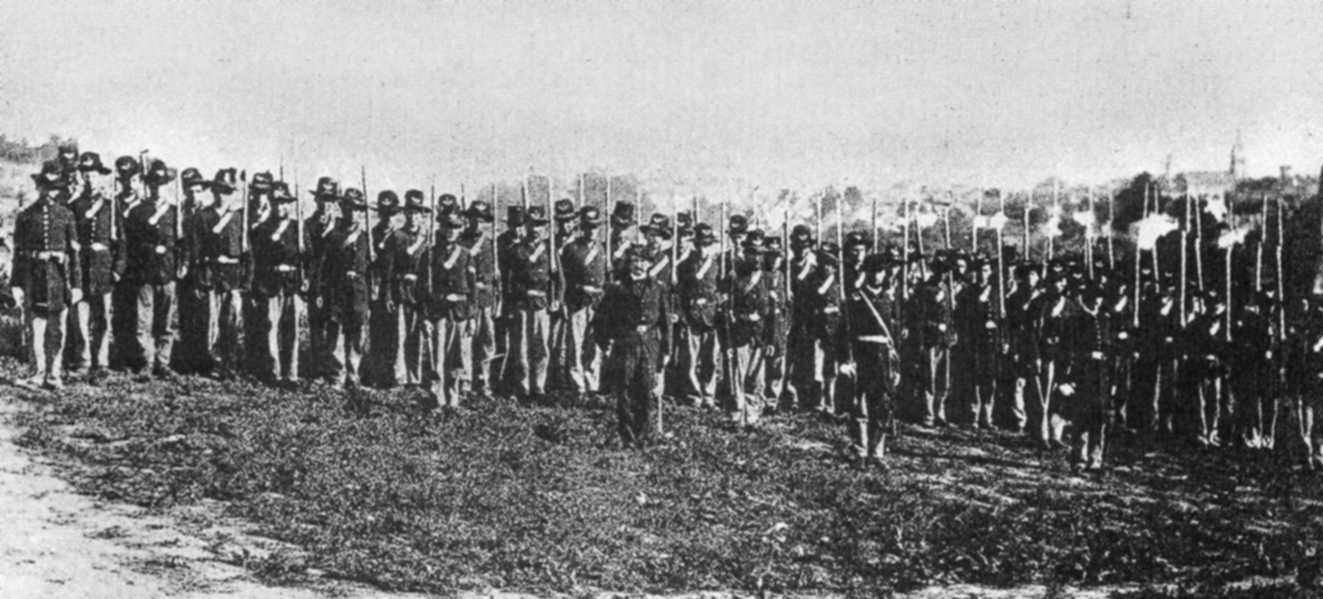

7th Wisconsin Infantry Volunteer Regiment, Iron Brigade, in Virginia in 1862. Wikimedia Commons

The formation of the Iron Brigade began in the spring of 1861, shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War. At the time, the Union Army was in desperate need of volunteers, and several states in the Midwest responded by raising their own regiments. Wisconsin quickly raised several regiments of its own.

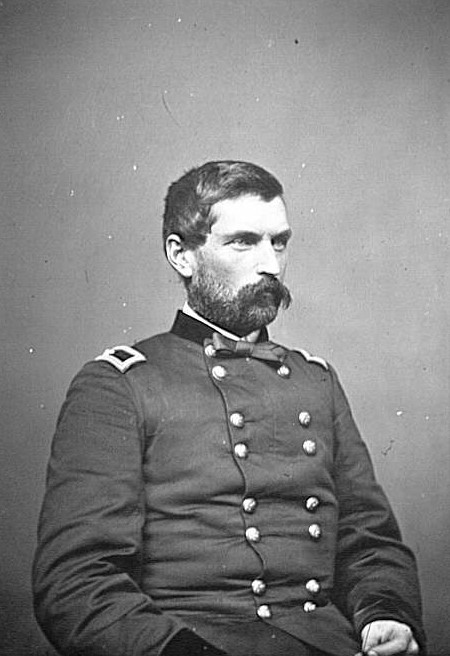

One of the most important figures in the formation of the Iron Brigade was Wisconsin Governor Alexander Randall, a staunch Unionist who believed the war was necessary to preserve the Union. He was also a shrewd politician who recognized the importance of having a strong military presence in the Midwest. To this end, Randall worked closely with several prominent military figures, including Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, who was tasked with organizing the Union troops in Wisconsin. Gibbon, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, had served in the Mexican War and had a reputation as an excellent military strategist.

Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, circa 1862-64. Library of Congress

Under Gibbon’s leadership, several regiments were raised in Wisconsin, including the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiments, which would later form the core of the Iron Brigade. These regiments were composed mostly of young men from the Midwest, many of whom were farmers, laborers, and tradesmen.

The men of the Iron Brigade were known for their discipline, tenacity, and fighting spirit. They were also noted for their distinctive black hats, which were part of their standard uniform. The hats, which were made of felt, were practical for keeping the sun out of their eyes and the rain off their faces, but they also gave the brigade a unique and recognizable appearance. At Gettysburg, for example, after engaging with the Midwesterners, the Confederates cried out “Hell, those are not raw militia, they are those ‘Black Hat Devils’ of the Army of the Potomac.”

The Iron Brigade saw its first major action at the Battle of Gainesville in August 1862. The brigade was under the command of Gibbon, who had recently been promoted to division commander, and it played a significant role in the battle. The fighting began in the late afternoon of Aug. 28, 1862, and resulted in a stand-up battle at ranges of 70 yards as both sides stood in an open field. It only ended when it became too dark to continue firing. That night, uncertain over the tactical situation and without orders, the brigade marched on to nearby Manassas Junction. This first battle proved to be a baptism by fire for the Brigade, as 725 men out of almost 2000 were casualties by the end of the fighting.

According to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, it was shortly after Gainesville that the Iron Brigade earned its famous nickname. At the Battle of South Mountain on Sept. 14, 1862, McClellan remarked to Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, “What troops are those fighting on the pike?” Hooker replied, “General Gibbon’s Brigade of Western men.” McClellan supposedly responded, “They must be made of iron.” While this story is only supported by McClellan’s own assertions, the Iron Brigade’s name did originate and see usage around this time in print media.

The Iron Brigade also played a crucial role in the Battle of Antietam. During the early parts of the battle of Sept. 17, 1862, fighting centered around a cornfield. However, after fierce artillery duels and small arms fire, the battle was reduced to a bloody stalemate. The Iron Brigade, stationed a few hundred yards to the west of the cornfield, saw significantly more success. While the hostilities were stalled to the east, they advanced down a turnpike close to the cornfield, sweeping aside Confederate soldiers and entering the field themselves. As they advanced, they were halted by a brigade of Confederates. However, after the Midwesterners returned fire, the Confederates fled, breaking the deadlock and allowing the other Union forces a reprieve. With the help of the Iron Brigade, the Union had broken the cornfield stalemate and resumed advancing on the Confederate positions. The day was not without its losses, though. By the end of the fighting, the Iron Brigade lost a total of 343 men killed or wounded. Due to the high number of casualties at Antietam, the 24th Michigan Volunteer Infantry was added to the brigade to reinforce its numbers.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, the Iron Brigade was held in reserve and did not see much action. However, the brigade’s courage and fighting spirit were once again on display at the Battle of Chancellorsville, where it fought tenaciously against superior Confederate forces from April 30 to May 6, 1863. While the Iron Brigade was instrumental in many early battles of the Civil War, it was at the Battle of Gettysburg that the Iron Brigade would earn its place in history.

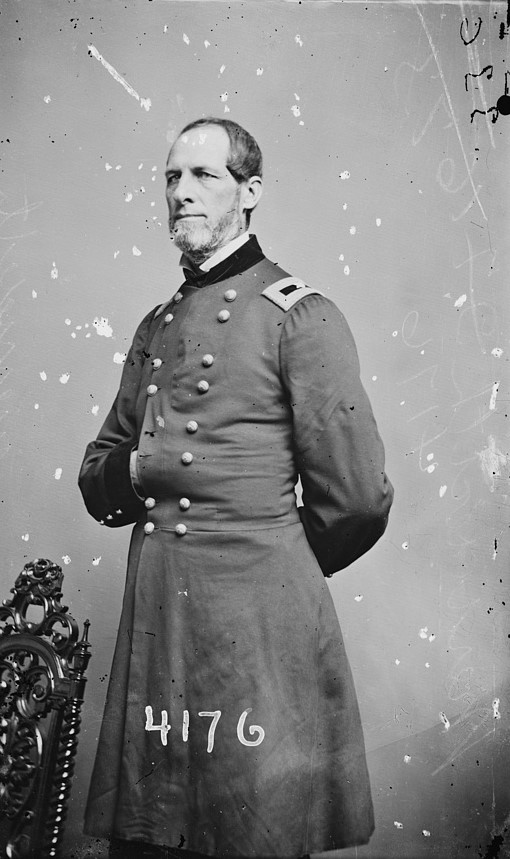

On July 1, 1863, the Iron Brigade was on the outskirts of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. At this time, the brigade was commanded by Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith, as Union leaders had assigned Gibbon to lead a different brigade at Gettysburg. Opposite them was the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee. Lee’s army was composed of some of the best troops in the Confederacy, and they were battle-hardened and confident. The Iron Brigade, on the other hand, was outnumbered and outgunned, but they were determined to hold their ground.

Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith, circa 1862-65. Library of Congress

As the day began, Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division moved toward Gettysburg. Heth’s objective was to seize supplies that were stored in the town. The Union cavalry, which was patrolling the area, clashed with Heth’s troops, and the battle began. Brig. Gen. John Buford, who commanded the Union cavalry, knew he was outnumbered, but was determined to delay the Confederates until reinforcements could arrive. The Iron Brigade was ordered to move to the area and engage the enemy.

The Iron Brigade arrived in the area just north of the town of Gettysburg around 10 a.m. They were ordered to advance against rebels’ positions along McPherson’s Ridge, a low hill that overlooked the town. The brigade was the first Union unit to engage the Confederates, and it quickly found itself facing a much larger enemy force.

The fighting was intense, and the Iron Brigade’s position was soon under heavy fire. The brigade was able to hold its ground, and it inflicted heavy losses on the Confederates. The Confederates pressed the Union infantry hard, but at one point over 200 Confederate soldiers were caught in an unfinished railroad cut nearby and were forced to surrender.

The battle raged on, and the Iron Brigade continued to hold its position. The Confederates launched several attacks, but the brigade repelled them. However, the brigade was suffering heavy casualties, and by the end of the day, it had lost 1,153 of its 1,885 men.

While the Iron Brigade and other Union forces fought hard, the numbers were not on their side that first day. By the end of July 1, over 30,000 Confederate soldiers overwhelmed the 20,000 Union Soldiers present. Despite the heavy losses, the Iron Brigade had accomplished its mission, buying time for the Union Army. The Union forces fled through Gettysburg but were able to take up strong positions on Cemetery Hill south of town. The brigade’s bravery and sacrifice on the first day of the battle reinforced its nickname “The Iron Brigade of the West,” and cemented its place as one of the most celebrated units in the Union Army.

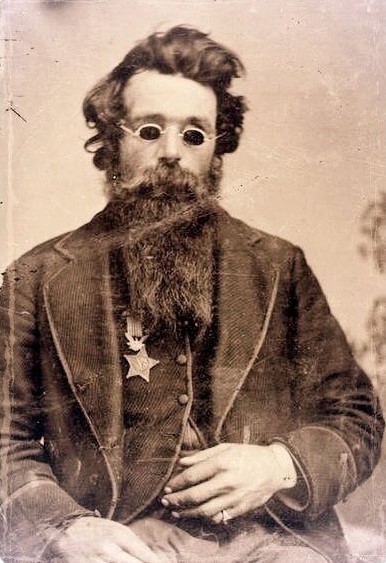

Bvt. Capt. Jefferson Coates wearing his Medal of Honor, circa 1870. Wikimedia Commons

For their bravery during Gettysburg, two men of the “Iron Brigade” were awarded the Medal of Honor. The first was Jefferson Coates, a sergeant with the 7th Wisconsin. During the height of the fighting on July 1, the 7th was involved in pushing part of Brig. Gen. James J. Archer’s Confederate brigade off McPherson’s Ridge. The Regiment then held that position before stubbornly retreating to Seminary Ridge. Coates earned his medal during this action. According to his Medal of Honor citation, he received his medal for “unsurpassed courage in battle, where he had both eyes shot out.” He mustered out of the Union Army in 1864 for disability. The second man, Cpl. Francis Asbury “Frank” Wallar (cited as “Waller”), served in the 6th Wisconsin. Also involved in the July 1 fighting, the 6th spent most of the early hours holding Seminary Ridge in reserve. However, they finally saw action when ordered to attack exposed Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph R. Davis. Forming up with the 14th Brooklyn and the 95th New York, the 6th advanced on the rebels who were entrenched in an unfinished railroad cut. During the fighting, Wallar captured the flag of the 2nd Mississippi Infantry and held it aloft, compelling the rest of the rebels to surrender. For this action, he received the Medal of Honor in December 1864. He served until the end of the War and afterward became a sheriff in Vernon County, Wisconsin.

The 2nd Wisconsin Infantry officers’ mess featuring Surgeon A.J. Ward, Maj. Thomas S. Allen, Lt. Col. Lucius Fairchild, and Col. Edgar O’Connor, as well as a butler, cook, and other staff. Wisconsin Historical Images

The Iron Brigade continued to fight in many other battles throughout the war, including the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. The brigade was finally disbanded in June 1865, shortly after the end of the war.

Today, the legacy of the Iron Brigade lives on in the many monuments and memorials that can be found throughout the Midwest and at Gettysburg National Military Park. Many modern units of the U.S. Army still carry the “Iron Brigade” moniker, in honor of those who fought in the Civil War. One of the most noteworthy is the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division. During the Cold War, they were sent to Baumholder, Germany, to defend Western Europe against the threat of Soviet invasion. In 1985, they adopted the “Iron Division” name, in honor of the resolve the original unit demonstrated at places like the Second Battle of Bull Run in 1862. Similarly, the 32nd Infantry Division took on the nickname, the “Iron Jaw Division.” An Army National Guard Unit during World War I and World War II, the 32nd was made up primarily of men from Wisconsin and Michigan. The unit’s traditional ties to the Civil War-era Iron Brigade influenced the creation of their nickname.

The brigade’s bravery, sacrifice, and fighting spirit continue to inspire generations of Americans and stand as a testament to the courage and determination of those who fought and died for their country during the Civil War.

Garet Anderson-Lind

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

“2nd BCT, 1st Armored Division.” U.S. Army. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://home.army.mil/bliss/index.php/units-tenants/1st-armored-division/2nd-bct-1st-armored-division.

“32nd Infantry (Red Arrow) Division.” Military Veterans Museum. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://mvmec.org/32nd-division/.

“‘Black Hat Devils’ of Iron Brigade, Fighting Unit, Confederates Find.” Wisconsin Local History and Biography Articles. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Newspaper/BA4377.

“Coates, Jefferson.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/jefferson-coates.

“Francis A. Waller.” The Hall of Valor Project. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/865.

“Gettysburg – McPherson’s Ridge – July 1, 1863 – 9:30am to 11:30am.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/gettysburg-mcphersons-ridge-july-1-1863-930am-1130am.

Herdegan, Lance J. “The Iron Brigade.” Essential Civil War Curriculum. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/the-iron-brigade.html.

Taliaferro, W.B. “Jackson’s Raid Around Pope.” In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 2, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Buel, 501-511. New York: The Century Co., 1887.