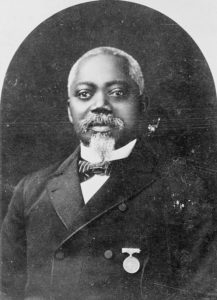

William Carney

Sergeant

54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment

February 29, 1840 – December 9, 1908

Sgt. William Carney. Library of Congress.

Sgt. William Carney was the first Black man awarded the Medal of Honor. Born into slavery, he later joined the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. As his regiment gained the crest of the parapet at the Confederate-held Fort Wagner in South Carolina, Carney took up the American Flag after earlier color bearers fell. He carried the flag to the fort, rallying and inspiring the men around him. Despite his injuries, he said, “Boys, I only did my duty; the old flag never touched the ground.”

William Carney was born on Feb. 29, 1840 in Norfolk, Virginia. His father, William Carney Sr., fled enslavement on the Underground Railroad. Carney Sr. settled in Massachusetts where he worked and saved money to buy his family’s freedom. In the late 1850s, the now-free Carney family moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts. Carney attended class where he learned to read and write. While he showed an interest in joining the ministry, he saw the onset of the Civil War as a call to serve in the U.S. Army. Carney stated that “when the country called for all persons, I could best serve my God serving my country and my oppressed brothers.”

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment formed after the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863. Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew led the organization of an all-Black volunteer regiment. Abolitionists, seeking to help end slavery, became leaders of the recruitment effort. Because so many men volunteered to serve in the Army, two regiments were created: the 54th and the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments. White commanding officers led and trained the Black volunteers. After completing training in May 1863, they set off to join the war.

The 54th deployed to Darien, Georgia where they were ordered to raid the town. Their officers criticized the use of the 54th to pillage and burn rather than to fight. However, the regiment soon engaged in their first battle at James Island, South Carolina on July 16, 1863. The Battle of Fort Wagner followed two days later. Under the command of Col. Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th led the 5,000 Union troops who marched on the fort in the evening of July 18, 1863. At the fort, 1,800 Confederate soldiers prepared for the attack. The Union Army’s naval fleet battered the fort with cannon fire throughout the day to weaken their defenses. When the 54th arrived at the fort, the Confederate Army showered them with bullets. Shaw adjusted the regiment’s advances and took them through the moat and up the slope leading to the fort.

As the battle raged on, Shaw was killed, but his regiment continued to fight. The 54th suffered heavy casualties with 280 of their 600 Soldiers killed, wounded, captured, or missing in action. More Union forces continued fighting in the battle that lasted several hours. Eventually, the Union Army was forced to withdraw from the battle, unable to break the Confederate hold on the site. This battle serves as a pivotal example of Black Soldier’s valor during the Civil War. The actions of the 54th inspired even more Black men to enlist.

During the Battle of Fort Wagner, Carney was severely injured. Yet, he still managed to save the American flag after previous color bearers fell. Carney said “I threw away my gun, seized the colors, and made my way to the head of the column” proclaiming, “I did but my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground.” This action displayed the pride the 54th took in their role as U.S. Army Soldiers and showed the bravery and military skills of the Black Soldiers. Due to his injuries, Carney was discharged from service in 1864 and returned to Massachusetts. The 54th continued to fight for the remainder of the Civil War, serving in Florida and South Carolina.

During the 1890s, 25th anniversary celebrations of the Civil War increased interest in the acts of heroism of American Soldiers. This led to an influx of Medal of Honor awards. In 1897 President William McKinley asked the Army to review the regulations for awarding the Medal of Honor. After their review, the Army decided that medal recipients needed to display gallantry and intrepidity to warrant the award. For his bravery, Carney was presented the Medal of Honor by President Theodore Roosevelt on May 23, 1900. This award marked Carney’s efforts at Fort Wagner, on July 18, 1863, as the first act by an African American to merit receipt of the Medal of Honor.

After returning home, Carney married Susannah Williams and had a daughter. He later became the first Black postal mail carrier in New Bedford, Massachusetts and the first documented Black postal mail carrier in the United States Postal Service (USPS). After retiring from the USPS, he served as a messenger at the Massachusetts State House. He died on Dec. 9, 1908 and is buried in New Bedford. His memory lives on as a representation of the valor and bravery of the Black Soldiers who served in the Union Army.

Jennifer Ezell

Education Specialist

Sources

National Park Service. “54th Massachusetts Regiment.” Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/54th-massachusetts-regiment.htm.

American Battlefield Trust. “William Carney.” Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/william-carney.

Hammond, Thomas M. “William H. Carney: The First Black Soldier to Earn the Medal of Honor.” Military Times, February 5, 2018. https://www.militarytimes.com/military-honor/black-military-history/2018/02/06/william-h-carney-the-first-black-soldier-to-earn-the-medal-of-honor/.

Home of Heroes. “William Harvey Carney.” 2018. https://homeofheroes.com/heroes-stories/civil-war/william-harvey-carney/.

The City of Norfolk. “William Harvey Carney.” Accessed January 17, 2021. https://www.norfolk.gov/3256/William-Harvey-Carney.

Widener, Robert. “At the Pinnacle of Heroism: The Medal of Honor.” VFW Magazine, June/July 2012. http://digitaledition.qwinc.com/article/At+The+Pinnacle+Of+Heroism%3A+The+Medal+of+Honor/1048974/109600/article.html.

Further Reading

Zwick, Edward, dir. Glory. 1990; Burbank, CA: TriStar Pictures.

Page, Jennifer. “William H. Carney.” National Park Service. Last modified December 10, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/articles/william-h-carney.htm.

Waters, Jane C. “Sergeant William H. Carney.” A Guide to New Bedford’s Black Heritage Trail. Boston: University of Massachusetts Boston, 1976.