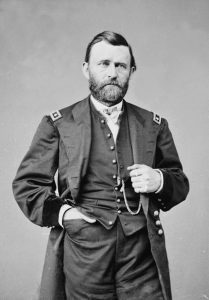

Ulysses S. Grant

General of the Army

United States Army

April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885

Ulysses S. Grant. Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

People, both past and present, have called General of the Army Ulysses S. Grant by many names, some fair and others not. Among them are hero, butcher, savior, and drunkard but perhaps the most accurate of all was the “American Sphinx.” Even for the people of Grant’s time, he was somewhat of a mystery. Thanks to the efforts of recent historians, Grant is much better understood today than when he was alive. The historical record reveals the story of a remarkable man who, through his intelligence, determination, iron will, and patriotism, helped lead the United States through one of the greatest times of crisis and chaos in the nation’s history. As general of the Army, he commanded hundreds of thousands of Soldiers during the Civil War, leading the Union Army to victory over the Confederacy. As president, he guided the nation through Reconstruction, helping to bind the wounds between North and South while empowering newly freed African Americans. Overblown allegations of drunkenness and corruption hurt his reputation, yet the soft-spoken Grant stands as an excellent commander who dedicated his life to serving the United States.

Born on April 27, 1822 to Jesse and Hannah Grant, the future president grew up in Point Pleasant, Ohio. They named him Hiram Ulysses Grant. He disliked working in the family’s tannery so his father worked to get him appointed as a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1839. A clerical error altered Grant’s name to “Ulysses S. Grant,” a name that he adopted for the rest of his life. Though talented in mathematics and an accomplished horseman, Grant graduated 21st out of his class of 39 cadets. In 1844, he became engaged to Julia Dent, the daughter of a Missouri plantation owner. The two married four years later in 1848 and eventually welcomed four children into their family.

Grant deployed with the 4th Infantry Regiment to fight in the Mexican War in 1846. Serving as the regiment’s quartermaster, he fought in several battles, including Resaca de la Palma and Chapultepec. He earned a brevet (temporary) promotion to captain and learned valuable skills that later served him well in the Civil War. After the Mexican War ended in an American victory, Grant was sent to several other duty stations, including Fort Humboldt in California. While there, allegations of excessive drinking caused Grant to resign from the Army on July 31, 1854. While guilty of the offense, Grant battled his addiction to alcohol throughout the rest of his life.

Grant struggled to support himself and his family as a civilian. After failing as a farmer and a businessman in Missouri, Grant and his family moved to Galena, Illinois, in April 1860 so he could clerk in his father’s store. By then, the storm clouds of secession and possible war loomed on the horizon. Though Grant had supported Democrats, he despised slavery, partly due to his upbringing in an abolitionist household, and had even freed an enslaved person he briefly owned in 1859. When the newly formed Confederacy opened fire on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Grant wrote that, “There are but two parties now: traitors and patriots. And I want hereafter to be ranked with the latter.”

Motivated by love for his country, Grant decided to help the Union cause by serving again in the Army. While the future president struggled in civilian life, the Civil War allowed him to thrive and put his talents to good use. On June 14, 1861, he was appointed as a colonel and was given command of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Shortly after, he was promoted to brigadier general on August 5. He proved to be a brilliant strategist, winning his first major victories later that year. Working closely with the Navy, he captured the strategically important Confederate forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862. The battles earned him the nickname “Unconditional Surrender Grant” for his uncompromising surrender terms. The stunning victories also drew the attention of President Abraham Lincoln, who promoted Grant to major general of volunteers.

Serving under the command of Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, Grant next led the Army of the Tennessee at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6 and 7, 1862. Grant’s force endured the full brunt of a ferocious enemy assault on the first day of the battle. Yet he refused to give in. That night, he told his good friend Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman that they would, “Lick ‘em tomorrow.” On April 7, with the addition of fresh reinforcements, Union forces counterattacked and drove the Confederates from the field. Grant had prevented disaster. While some in the Army leadership wanted Grant removed from command due to the high casualties and allegations of drunkenness, Lincoln refused, declaring, “I cannot spare this man. He fights.”

After defeating rebel forces in several battles around Corinth, Mississippi, Grant began an offensive against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a heavily fortified enemy stronghold. After months of fighting and a lengthy siege, the Army of the Tennessee captured Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. Regarded by historians as one of the most important victories of the war, the loss of Vicksburg devastated the enemy as they were no longer able to use the Mississippi River to move troops or supplies. The victory catapulted Grant to nationwide fame and Lincoln promoted him to major general in the Regular Army (At this time, Grant was still a commander of volunteers). He next defeated rebel forces near Chattanooga, Tennessee at the Battles of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge on November 24 and 25, 1863. Lincoln responded by promoting Grant to lieutenant general, a rank not held by anyone since George Washington, a stunning rise for someone who worked as a store clerk less than three years before. With command of all Army forces, Grant devised a plan to finally win the war. Believing that the enemy could not defend their territory everywhere, he sent five separate armies to attack the Confederacy at several points at once.

Grant attached himself to the Army of the Potomac and ordered its commander, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, to attack the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Grant and Meade engaged Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s army in a series of bloody battles known as the Overland Campaign in May and June of 1864. Grant relentlessly attacked the enemy, driving Lee back closer to Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. Yet Grant suffered stunning casualties; the Army of the Potomac lost over 54,000 Soldiers killed, wounded, or captured in just a few weeks. Undaunted, he besieged the vital railroad hub of Petersburg south of Richmond beginning in June 1864. Both Grant and Lee knew that if Petersburg fell, Richmond would as well.

Over the next several months, Union Army forces made steady progress across the Confederacy with Grant content to continue besieging Petersburg until it was captured. Finally, on April 2, 1865, the Confederates fled Petersburg and Richmond. Grant pursued the Army of Northern Virginia until Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Although some Confederates still resisted, Lee’s surrender essentially marked the end of the Civil War. Grant gave the defeated rebels generous terms of surrender, a merciful act that made him even more famous in the North and South.

After Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865, Grant worked with incoming President Andrew Johnson to bring the South back into the Union, a period known as Reconstruction. Congress promoted him to the new rank of general of the Army in 1866, and he briefly served as secretary of war in 1867. Many Northerners wanted to punish the South for the war, but Grant sought to be lenient to the South as long as they accepted the rights of formerly enslaved African Americans. With the rise of white terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, Grant grew concerned for the welfare of newly freed people. When Congress impeached President Johnson over his Reconstruction policies, Grant believed that he was the only person who could reunite the North and South. The Republican Party nominated him for president and he defeated the Democratic candidate, Horatio Seymour, in the 1868 presidential election.

Grant served two terms as president from 1869 to 1877. He worked to improve the economy and enact Reconstruction measures throughout his terms in office but was particularly committed to protecting the rights of formerly enslaved African Americans in the South. In 1870, he oversaw the passage of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protected the right to vote, and created the Department of Justice to battle the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups. He also wanted to grant citizenship to Native Americans, appointing Ely S. Parker, a Seneca tribal member, to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs. However, Grant authorized the use of force by Army elements against hostile tribes, leading to the outbreak of several wars, such as the Great Sioux War, in 1876-77.

Grant’s administration was also marked by several high profile scandals. Members of his administration, such as his private secretary Orville Babcock, were found guilty of corruption and financial crimes during his terms in office. Although Grant was never guilty of corruption, he often trusted friends and colleagues who were. These scandals hurt his public image, leading many people to believe Grant himself was corrupt. Despite these scandals, Grant managed to bring North and South back together as one nation by the end of his final term. However, many of his civil rights achievements were undone following his administration, leading to the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan and the rise of Jim Crow segregation in the South.

After he left office, Grant traveled the world and invested in several business ventures. In 1884, he was diagnosed with terminal throat cancer, likely caused by his habit of smoking ten to twenty cigars a day. To ensure his family had enough money, the dying Grant wrote his memoirs, which became a bestseller after its publication in 1885. He died on July 23, 1885, having finished his memoirs only a few days earlier. Grant had lived a life of war, peace, and service. His memory lives on as the embodiment of loyalty, selfless service, and integrity to the United States.

A. J. Orlikoff

Lead Education Specialist

Sources

Achenbach, Joel. “U.S. Grant was the great hero of the Civil War but lost favor with historians.” Washington Post, April 24, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/us-grant-was-the-great-hero-of-the-civil-war-but-lost-favor-with-historians/2014/04/24/62f5439e-bf53-11e3-b574-f8748871856a_story.html.

Chernow, Ron. Grant. New York: Penguin Books, 2017.

Greene, Bryan. “Created 150 Years Ago, the Justice Department’s First Mission Was to Protect Black Rights.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 1, 2020.https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/created-150-years-ago-justice-departments-first-mission-was-protect-black-rights-180975232/.

Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

Stockwell, Mary. “Ulysses Grant’s Failed Attempt to Grant Native Americans Citizenship.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 9, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ulysses-grants-failed-attempt-to-grant-native-americans-citizenship-180971198/.

“The Racial Views of Ulysses S. Grant.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 66 (2009): 26–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20722155.

“Ulysses S. Grant.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed December 4, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/ulysses-s-grant.

Waugh, Joan. “Ulysses S. Grant: Life in Brief.” Miller Center, University of Virginia. Accessed December 5, 2021. https://millercenter.org/president/grant/life-in-brief.

Additional Resources

American Battlefield Trust. “Overland Campaign Animated Map.” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/overland-campaign-animated-map.

Grant, Ulysses S. The Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. 2 vols. New York: Charles L. Webster and Company, 1885.