Nathanael Greene

Major General

United States Army

August 7, 1742 – June 19, 1786

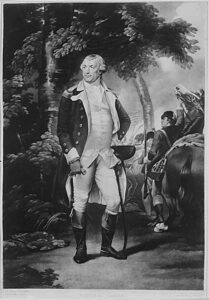

Portrait of General Nathanael Greene by Valentine Green, executed by J. Brown after Charles Willson Peale, 1785. National Archives

Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene rose to become one of the most celebrated American officers in the Revolutionary War. Best known for his clever campaign against the British army in the Southern states, Greene also fought in the battles of Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, and Monmouth Courthouse. However, his reputation as one of Washington’s most trusted generals may not seem likely at first glance.

Greene was born in 1742 to a prominent Quaker family in Warwick, Rhode Island. As a boy, he was markedly curious about the world. Despite the Quaker belief against early education, Greene convinced his father to hire a tutor to teach him philosophy, religion, literature, and mathematics. After his father’s death in 1770, young Greene moved to Coventry, Rhode Island, to take charge of the family-owned foundry. There, he purchased land and built a home he called Spell Hall complete with a large library where Greene could spend his free time doing what he loved most: reading. Four years later, Greene met and married Catharine Littlefield, the daughter of a Rhode Island legislator. The couple settled into Spell Hall and had seven children together, five of whom survived to adulthood.

As tensions strained between Great Britain and the American colonies, Greene remained relatively neutral. However, his opinion began to change when British Navy officer William Dudington seized a ship owned by Greene’s firm. After filing an unsuccessful lawsuit against Dudington for damages to the ship, a Rhode Island mob descended upon Dudington’s own vessel, the Gaspee, and torched it. The ordeal became known as the Gaspee Affair, an event which hastened Greene’s disillusionment with the British government. He also grew increasingly wary of his family’s Quaker faith and was barred from Quaker meetings in 1773 because he drilled with the local militia.

In 1774, Greene organized a company of Rhode Island militia known as the Kentish Guards following the passage of the Intolerable Acts. Because of a limp he developed during his childhood, Greene did not assume command of the unit and remained a private. Despite this, Greene was appointed to command the Rhode Island Army of Observation, which joined the colonial forces besieging Boston after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. In June 1775, the Second Continental Congress established the Continental Army and promoted Greene to brigadier general under the command of General George Washington.

Washington grew to rely on Greene as one of his most trusted generals. Although absent from the Battle of Long Island due to illness, Greene participated in the Battle of Fort Washington and helped lead the Continental Army’s retreat into New Jersey and Pennsylvania. After the American victories at Trenton and Princeton, Greene led a division throughout the Philadelphia Campaign. At the Battle of Brandywine, he and his men saved Washington’s Army from complete destruction by buying time for the Continentals to escape. Later that year, Greene helped select the winter encampment at Valley Forge where his wife Catherine joined him. In 1778, he reluctantly accepted the position of quartermaster general, an assignment in which he oversaw the supplies and rations of the army. Just as Maj. Gen. Baron von Steuben drilled the weary band of Continentals into an effective army, Greene made tremendous reforms to the quartermaster’s department to ensure greater efficiency. That winter, Greene also rallied to Washington’s defense against the so-called Conway Cabal, a contingent of Continental Army officers and politicians that criticized the commanding general.

By 1780, British forces had routed the Continental Army in the Southern states. To deal with this threat, Washington appointed Greene commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army. In 1781, outnumbered and outgunned by the British army, led by Lt. Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis, Greene employed evasive tactics to even the odds. Greene led the Continentals on a strategic retreat north through the Carolinas, allowing him to outmaneuver Cornwallis. At the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Cornwallis defeated Greene’s larger army, but at the cost of heavy casualties.

After the bloody battle, the badly bruised British army withdrew to Wilmington, North Carolina. Greene initially gave chase, he soon turned his Army south to besiege Camden, South Carolina. There, British commander Francis, Lord Rawdon attacked Greene’s men at the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill. The battle ended in an American defeat, but Rawdon’s retreat from backcountry South Carolina allowed Greene to seize the initiative once again. On June 18, 1781, the Continentals besieged a British fort at Ninety Six, South Carolina. The British and Loyalists were able to lift this siege, but soon retreated toward Charleston. Greene’s army next engaged the British at the Battle of Eutaw Springs, South Carolina, in September. Though Greene’s men retreated from the field, they managed to inflict greater losses on the enemy. The battle also forced the British to withdraw to the protection of Charleston, granting control of South Carolina to the Continentals. Congress awarded Greene a gold medal in recognition for his success at Eutaw Springs.

After the conclusion of hostilities in 1781, Greene rose to prominence as one of the most popular heroes of the Revolution. For his successful campaign in the Carolinas, he earned the nickname “Savior of the South.” The state governments of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia also awarded him large tracts of land and money in honor of his victories. In the two years between the surrender at Yorktown and the Treaty of Paris, Greene continued to skirmish with Loyalist militias throughout the South. He also struggled to maintain proper clothing and food for his Army with low funds.

After resigning his commission in 1783, Greene returned to Newport, Rhode Island, but did not stay long. He declined two political appointments: one as the first secretary of war (which went to his friend Maj. Gen. Henry Knox) and the other as a commissioner to negotiate treaties with Native Americans. Instead, Greene retired to his plantations in the South. He made his home at Mulberry Grove outside of Savannah, Georgia, and began settling his wartime debts. Greene died on June 19, 1786, from sunstroke, leaving behind his wife Catherine and their five children. His body was initially buried in Colonial Park Cemetery in Savannah. However, in 1902, Rhode Island Society of the Cincinnati President Asa Bird Gardiner launched a successful campaign to reinter Greene’s remains to Johnson Square in Savannah.

Greene is remembered by historians as one of the best generals in the Revolutionary War, second only to Washington. His legacy as the “Savior of the South” lives on today. Numerous towns, cities, and counties are named after him, including Greensboro, North Carolina, Greensburg, Pennsylvania, and Greenville, South Carolina. Likewise, statues and memorials to Greene stand in places like Washington, D.C., Providence, Rhode Island, and Savannah.

Evan Portman

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

Anderson, Lee Patrick. Forgotten Patriot: The Life and Times of Major-General Nathanael Greene. Irvine, CA: Universal Publishers, 2002.

Carbone, Gerald M. Nathanael Greene: A Biography of the American Revolution. London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Golway, Terry. Washington’s General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2006.

Greene, George W. Nathanael Greene: Major-General in the Army of the Revolution. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1846.