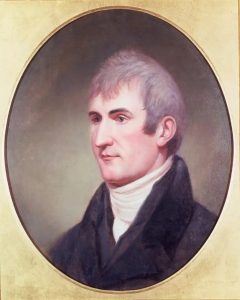

Meriwether Lewis

Captain

Corps of Discovery

1774 – 1809

“Portrait of Meriwether Lewis” by Charles Willson Peale, 1807. Independence National Historic Park.

Meriwether Lewis was a U.S. Army captain, explorer, and governor during the early years of America’s development and expansion. As an explorer his studies, research, and writing paved the way for Americans to move westward. As a governor, his laws and policies set the tone for the next century of American settlement in the west.

Born in 1774, Lewis’s life started as America was becoming a country. He was the oldest child of Lucy Meriwether and William Lewis and spent his early years in Albemarle County, Virginia. When he was five years old, his father passed away from medical complications while serving in the Continental Army. Soon after, his mother remarried and moved the family to Georgia. Instead of attending school, Lewis spent most of his time outdoors where he came to love hunting and nature.

When he turned 13, Lewis’s parents sent him back to Virginia for a more formal education, but he still visited his family in Georgia often. When his stepfather passed away in 1792, Lewis moved back to Virginia. He learned to manage the family’s plantation, Locust Hill, as well as the people enslaved to work his lands. During these years, Lewis also became acquainted with the owner of a large neighboring plantation, Thomas Jefferson. He and Jefferson shared a deep interest in the natural sciences and Lewis often borrowed books from Jefferson’s library.

Following his father’s footsteps, Lewis enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1795 at the age of 21 and excelled through the ranks to captain. He served as a rifleman for a time under a man by the name of William Clark. When Jefferson became president in 1801, he asked Lewis to be his personal secretary. Lewis spent two years working with the president before Jefferson offered him his next opportunity.

Jefferson had long believed there was a water passage to the West. After other failed attempts at sending explorers to the Pacific, the new president asked Lewis to lead an expedition. In 1803, President Jefferson bought a large amount of land from France. This region stretched from present-day Louisiana to Montana and was already home to many Native Americans. Native leaders did not get a say in the sale of their land. Jefferson tasked Lewis’s expedition with contacting and learning more about these Native groups, mapping the area, and taking notes on the animals and plants they encountered along the way.

Congress looked to the U.S. Army for suitable members of the expedition. Lewis, now a 28-year-old captain, well versed in military and outdoor skills, seemed well suited to lead the team. The president arranged for Lewis to move to Philadelphia to study wayfinding and medicine. Afterward, Lewis selected his friend and former commander, William Clark, to be his co-captain for the expedition. Together they gathered a team of Soldiers and the necessary supplies for what they knew would be a very long journey.

This team, later called the Corps of Discovery, departed from a camp outside St. Louis, Missouri, on May 14, 1804. The expedition ultimately traveled more than 8,000 miles to the Pacific Ocean and back to St. Louis. Lewis and Clark spent much of the journey representing America in peace talks and trade with leaders of the Native people groups they met. Lewis served as the team’s natural scientist. He collected plants and animals to send back home for others to study and wrote about the people they met and their cultural practices.

During this period, the trade of fur was one of the largest businesses in North America. Native groups, Americans, and Canadians all took part in hunting beavers for fur to trade for things like food, jewelry, or weapons. As they traveled, Lewis kept maps of rivers and beaver habitats. Later, these maps gave Americans an advantage in the fur trade.

The nearly three years away from home left Lewis with much to take care of when the corps returned home in 1806. Jefferson rewarded Lewis for his hard work with 1,600 acres of public land which fell under his care as well as the family plantation in Virginia. A year later, Jefferson appointed Lewis governor of the Louisiana Territory. Lewis, being more interested in trying to write a book and start a family, refused to move west to govern for more than a year.

When he arrived in St. Louis, tensions were high between the American settlers, the Osage, and the Cherokee people who were all competing for control. As governor, Lewis settled these disputes, favoring American claims with plans to force Native peoples to move elsewhere. He instated new laws prohibiting slaves from purchasing their freedom and barring women from owning land. Lewis struggled with government life. His inconsistency in writing and communication strained his relationship with officials in Washington, D.C.

His journey with the Corps of Discovery cost Lewis a significant amount of his own money, which he expected the government to pay back. The Department of War did not see the necessity of some expenses, such as tobacco traded with Native American groups, and refused to pay. This delay in funds left Lewis in a difficult financial situation and threatened to ruin his reputation. In 1809, at the age of 35, he set off for Washington to meet with government officials and plead his case. Unfortunately, Lewis never made it to D.C. Part way through his journey, on October 11, 1809, an innkeeper found him dead in his room in Tennessee. His servant and the innkeeper buried him nearby and sent word to his friends. While historians disagree on the exact details of Lewis’s death, most agree that his life was an important contribution to American history. Forty years after his death, the state of Tennessee paid for and created a monument on his burial site that remains a National Monument to this day.

Michela Kuykendall

Museum Specialist

Sources

Danisi, Thomas C., and John C. Jackson. Meriwether Lewis. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2009.

Buckley, J. H. “Meriwether Lewis.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Last modified August 14, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Meriwether-Lewis.

Hogan, David W. Jr., and Charles E. White. The U.S. Army and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2002.

Burd, Frank. Lewis & Clark: The Adventure into the West. John Hinde Curteich, Inc, 2001.

Additional Resources

“Interactive Lewis and Clark Trail.” PBS LearningMedia. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://thinktv.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/f5705ebc-dc5f-4407-9ec5-0ecb837c5ff2/interactive-lewis-and-clark-trail/#.YBGpO5NKhQI.