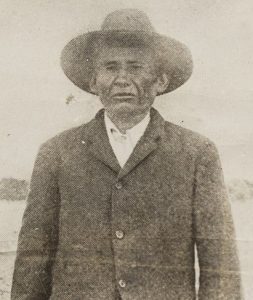

Kayitah

U.S. Indian Scouts

1856 – 1934

Kayitah, circa 1904. Cropped. National Archives.

Like so many other U.S. Indian Scouts, Kayitah risked his life on behalf of a country that did not fully accept him. Promised veteran’s benefits in return for assistance, Kayitah and other Apache scouts joined the United States in the long-fought Apache Wars. Later, Kayitah and his family struggled for decades to receive the payment promised for his service. His story echoes that of countless other indigenous people who supported the United States, only to be faced with conflict, dishonesty, and a hard-fought battle for their rights.

The Apache Wars shaped the landscape of the American southwest throughout the late 19th century. The United States inherited the conflict upon Mexico’s land cession after the Mexican War in 1846. Apache nations inhabited the disputed territory for generations prior to the arrival of European colonizers. Upon the legal transfer of the land to the U.S. government, the Army planned to move the Apache nations to reservations across the country, limiting their traditional nomadic lifestyle. In response, members of Apache nations led raids and fought in skirmishes against the Army, often led by Geronimo, an Apache medicine man. Over the course of the conflict, Geronimo escaped from U.S. military control three times and was considered to be key to the continuation of Apache resistance.

Born December 31, 1856, Kayitah grew up on Chiricahua Apache land, also known as the Arizona Territory. He married Lupe and had a son, Kent Kayitah, in 1886. Throughout his youth, Kayitah bore witness to the growing conflict between his community and the American government. He ultimately decided to support the United States, believing it would be in his best interest and that of his family. He enlisted in the Army five times throughout his life, first in November 1885. He reenlisted in July 1886 and served with Company E of the Indian Scouts, during which time he was instrumental in the surrender of Geronimo to the U.S. Army.

After Geronimo’s third escape from military custody in the summer of 1886, Lt. Charles B. Gatewood of the 6th Cavalry employed Kayitah and another Apache Indian Scout, Martine, to aid in the search for him. Kayitah and Martine were both members of the Chiricahua, like Geronimo, and knew him personally. They were thus sent to locate him with a message from Gatewood urging Geronimo to surrender. In return, Kayitah and Martine were promised a lifelong pension, as well as payment upfront. Kayitah and Martine successfully convinced Geronimo to meet with Gatewood, where Geronimo was informed that the home he hoped to return to no longer existed. After some conversation, Geronimo agreed to surrender and follow the military to Florida as a prisoner of war.

Geronimo’s surrender, thanks in large part to Kayitah and Martine’s efforts, was lauded as a great victory for the U.S. military. However, a miscommunication resulted in the removal of Kayitah and Martine to Florida as prisoners of war with Geronimo. The men were held there for a year. Beyond this gross oversight, neither man received the compensation due to them. After his release, Kayitah returned to New Mexico, where a reservation had been founded in Whitetail, close to the Chiricahua Apache ancestral land. Despite the injustices Kayitah faced in the Indian Scouts, he enlisted three more times through 1914, when he earned an honorable discharge. While he earned a baseline scout pension of $20 a month, the additional rewards he was promised had not materialized. Sitting in an interview with Kayitah in 1925, nearly 40 years after his most valuable contribution to the U.S. military, O. M. Boggess, commissioner for Indian Affairs, wrote: “It does seem that a real injustice was done to these… scouts, who risked their lives and were largely instrumental in bringing in Geronimo.” Boggess wrote a formal recommendation to the War Department requesting just compensation for both Kayitah and Martine. Kayitah’s pension gradually increased, first to $30 a month, then to $50, and he received a large lump sum payment. Upon his death in February 1934, the Veterans Administration paid for his burial.

After his death, Kayitah’s wife, Lupe, continued to face opposition from the War Department. While they had been married for nearly 50 years, the U.S. government did not recognize their marriage ceremony. It therefore took a year after her husband’s passing for Lupe to receive spousal benefits, and a later request for back payment was denied. While some Indian Scouts later earned Medals of Honor for their service, Kayitah is one of hundreds of marginalized Soldiers who served valiantly with little credit or reward.

Delaney Brewer

Co-lead Education Specialist

Sources

“The Apache Wars Part II: Geronimo.” National Parks Service. Last modified August 19, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/chir/learn/historyculture/apache-wars-geronimo.htm.

Barra, Allen. “’The Apache Wars’ Gives History of Forgotten Conflict.” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 2016. https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/books/ct-prj-apache-wars-paul-andrew-hutton-20160503-story.html.

Hutton, Paul Andrew. The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History. New York: Broadway Books, 2017.

Kratz, Jessie. “‘A Real Injustice Was Done to These Two Old Scouts’: The VA Claim File of an Indian Scout.” Pieces of History (blog). October 31, 2017. https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2017/10/31/a-real-injustice-was-done-to-these-two-old-scouts-the-va-claim-file-of-an-indian-scout/.

“Native History: Apache Scout Involved in Geronimo’s Surrender Dies.” Indian Country Today, August 1, 2013. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/native-history-apache-scout-involved-in-geronimos-surrender-dies.

Plante, Trevor K. “Lead the Way: Researching U.S. Army Indian Scouts, 1866–1914.” National Archives and Records Administration. Last modified March 11, 2019. www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2009/summer/indian.html.