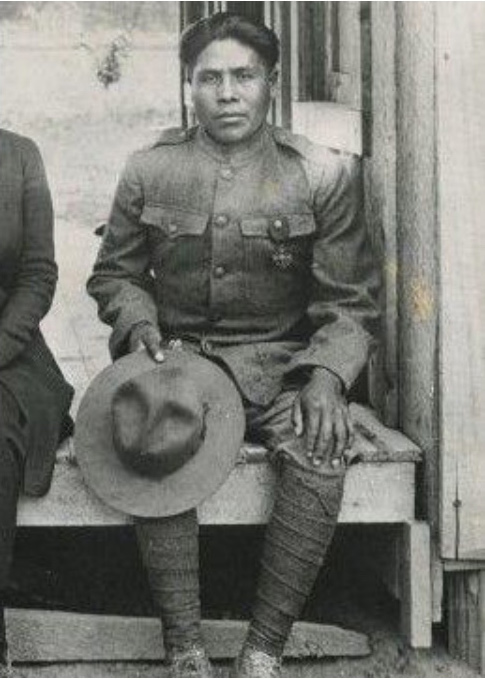

Joseph Oklahombi

Private First Class

143rd Regiment36th Division

May 1, 1895 – April 13, 1960

Joseph Oklahombi was one of the thousands of Indigenous Soldiers who enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War I at a time when not all Native Americans were considered U.S. citizens. Oklahombi’s battlefield feats and his native language were instrumental in the defeat of the German Army during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive at the end of the Great War. He distinguished himself by fighting bravely for his country and receiving numerous awards. At a pivotal moment in history, Oklahombi and nineteen other Indigenous speakers stepped up to become the original Choctaw Code Talkers of World War I. They used their native language to help create an unbreakable “code.”

Oklahombi was born to Ramsey and Minnie Oklahombi in Red River County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Oklahombi intermittently attended Armstrong Academy, a state-run boarding school for Indigenous children in the local area. During this period, the goal of the boarding schools was to assimilate Indigenous children into white society. Oklahombi and thirteen of the original Choctaw Code talkers attended Armstrong Academy together. The children were taught reading and writing in English. In addition, the schools often operated in a militaristic style with short haircuts, uniforms, unit organizations, and drill. The boarding schools prohibited the children from speaking in their native language and they received corporal punishment if caught. Oklahombi endured his childhood school days and eventually enlisted in the United States Army out of his sense of duty to protect the country.

Due to the German Army being adept at listening to and intercepting Allied messages, an officer in the 142nd Infantry decided to experiment with Choctaw Soldiers transmitting messages through the telephone in their native language. This was the first time the Choctaw language was used to transmit messages during the war. Nineteen Choctaw Soldiers, including Joseph Oklahombi, were recruited to the telephone squad from the 141st, 142nd, and 143rd infantry regiments.

To develop the code, the Soldiers had to create special military terms in their native language. For example, the Choctaw Soldiers equated a grenade with a “stone,” regiment became “tribe,” and battalions were equated to “grains of corn.” That way, a Code Talker could understand and translate the message that the Choctaw Soldiers were relaying on the other end of the telephone. The Army placed Choctaw Soldiers in all headquarters units to utilize their language abilities. Once the Soldiers began speaking in their native language over the radio, the Germans were unable to decipher the messages and counterattack. “The enemy’s complete surprise is evidence that he could not decipher the messages,” Col. Alfred Wainwright Bloor, commander of the 142nd Infantry, later wrote in an official report. The Choctaw coordinated an artillery attack that took the Germans by surprise. This surprise resulted in a much-needed victory for the 36th Division. A captured German soldier wanted to know what language the Soldiers were speaking and was told: “American.”

The Choctaw Code Talkers’ success impacted not only the battlefield but also influenced future military operations. The publicity of their work by their commanding officers in newspapers and public statements encouraged the recruitment and training of other Indigenous speakers for the same task. Code talking was also employed in World War II. Once again Indigenous Soldiers using codes based on their native language were successful including the Marine Corps Navajo code remaining unbreakable.

On the battlefield, Oklahombi was indispensable during the battle at St. Étienne, in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive from Oct. 6 to Oct. 29, 1918. The operation occurred in a 12-mile section of the Meuse River valley which was flanked by the thick Argonne Forest on one side and the Meuse River on the other. The German Army had fortified their positions with trenches, barbed wire, and concrete along the river valley. On April 8, 1918, Oklahombi and 23 men from Company D, 141st Infantry came across a group of Germans and proceeded to engage them. The men captured the machine gun and turned it on the enemy. Their successful maneuver captured 171 German soldiers, weapons, and ammunition, and killed 79 enemy soldiers. Oklahombi and his unit held off the German Army for four days, against gas attacks and artillery, while having no food or water.

For their actions, Oklahombi along with his fellow Soldiers in Company D were awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action, to be placed upon the ribbon of their Victory medal. He also received the French Croix de Guerre with a Silver Star for gallantry in action for the same battle.

The Armistice was signed on Nov. 11, 1918, effectively ending the war. Oklahombi returned to the United States on June 3, 1919, and was discharged a few weeks later. He resided in Wright City, Oklahoma with his wife Agnes and son Jonah. Soon after, Hollywood approached him for a role in a World War I movie but he turned it down because he did not think there was anything glamorous about war. He lived out his life hunting, fishing, and farming the land that he loved until he was tragically struck by a vehicle while walking beside the road. He was 64 years old. Oklahombi was buried in Yaskau Cemetery, Broken Bow, Oklahoma with full military honors. He was known for being a modest man, and his son stated, “He didn’t talk about what he had experienced in the war.”

Posthumously, he was among the Code Talkers formally recognized by the Choctaw Nation with the Choctaw Medal of Valor in 1986. He and the Code Talkers received the Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Merite (Knight of the National Order of Merit) presented by the French government on the steps of the Oklahoma State Capitol in 1989. In 2008, Congress passed the Code Talker Recognition Act, which recognized all Code Talkers with a Congressional Gold Medal, as well as the Congressional Silver Medal for each surviving Code Talker or family member. A bridge in McCurtain County, Oklahoma was also built in his honor. Over the years, there was immense pressure to upgrade his award to the Medal of Honor, however, that has not occurred.

There is no doubt the Army’s success in World War I can be attributed to Indigenous Soldiers like Oklahombi. He along with the other Choctaw Code Talkers used their heritage, to propel the Allies towards victory. Their service is a testament to the courageous and selfless service of Indigenous Soldiers who have served the Army since its founding.

Christine Ortiz

Education Specialist

Sources

Blakemore, Erin. 2019. One of the Last Navajo Code Talkers, Whose Native Tongue Stumped WWII Enemies, Has Died | HISTORY. https://www.history.com/news/wwii-navajo-code-talker-fleming-begaye-dead.

Cambridge Sentinel. 1921. “Joseph Oklahombi: Choctaw War Hero.” October 29, 1921. https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Sentinel19211029-01.1.1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-.

“CHOCTAW CODE TALKERS.” n.d. Choctaw Nation. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.choctawnation.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/code-talkers-educational-booklet.pdf.

“Choctaw Schools | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.” n.d. Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=CH049.

“Code Talkers.” n.d. Choctaw Nation. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.choctawnation.com/about/history/code-talkers/.

“First of twenty-three bridges dedicated to honor Choctaw WWI and WWII heroes – World War I Centennial site.” n.d. World War I Centennial Commission. Accessed October 22, 2024.

https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/communicate/press-media/wwi-centennial-news/4842-first-of-twenty-three-bridges-dedicated-to-honor-choctaw-wwi-and-wwii-heroes.html.

Greenspan, Jesse. 2014. How Native American Code Talkers Pioneered a New Type of Military Intelligence | HISTORY. https://www.history.com/news/world-war-is-native-american-code-talkers.

Hall, Sharon. 2014. “Tombstone Tuesday: Joseph Oklahombi.” Digging History. https://digging-history.com/2014/11/11/tombstone-tuesday-joseph-oklahombi/.

Harlow, Victor E. Harlow’s Weekly (Oklahoma City, Okla.), Vol. 20, No. 39, Ed. 1 Friday, October 21, 1921, newspaper, October 21, 1921; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. (https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc1600182/: accessed October 6, 2024), The Gateway to Oklahoma History, https://gateway.okhistory.org; crediting Oklahoma Historical Society.

Hayes, Richard L. n.d. “Choctaw Code Talkers in World War I.” Warfare History Network. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/choctaw-code-talkers-in-world-war-i/.

“Joseph Oklahombi.” n.d. Wikipedia. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Oklahombi.

“Joseph Oklahombi (1895-1960).” 2024. WikiTree. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Oklahombi-1.

“Joseph Oklahombi’s story inspires students.” 2015. The Oklahoman. https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/military/2015/06/04/joseph-oklahombis-story-inspires-students/60742159007/.

Meadows, William C. 2021. The First Code Talkers: Native American Communicators in World War I. N.p.: University of Oklahoma Press.

Miles, Dennis. “Educate or We Perish”: The Armstrong Academy’s

History as Part of the Choctaw Educational System, article, Autumn 2011; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. (https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc2016981/: accessed October 6, 2024), The Gateway to Oklahoma History, https://gateway.okhistory.org; crediting Oklahoma Historical Society.

“National Museum of the United States Army.” n.d. National Museum of the United States Army. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.thenmusa.org/articles/world-war-i-code-talkers/.

“Oklahoma Military Hall of Fame.” n.d. Oklahoma Military Hall of Fame. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.okhistory.org/historycenter/militaryhof/inductee.php?id=364.

“Oklahombi, Joseph | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.” n.d. Oklahoma Historical Society. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=OK091.

Underwood, Ginny. 2019. “Honoring WWI code talker, Native veterans | UMNews.org.” UM News. https://www.umnews.org/en/news/honoring-native-american-united-methodist-veterans

Winterman, Denise. ”World War One: The Original Code Talkers.” May 19, 1914. BBC News. Accessed October 31, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-26963624