John Laurens

Lieutenant Colonel

Continental Army

October 28, 1754 – August 27, 1782

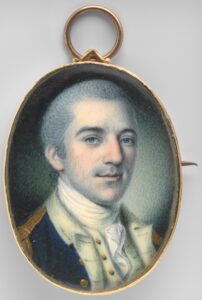

Portrait of John Laurens by Charles Willson Peale, 1780. National Portrait Gallery

Lt. Col. John Laurens served under General George Washington during the American Revolution and was a valued member of Washington’s “military family.” During the war, Laurens planned to recruit enslaved men for the Continental Army. In return for serving in the military, the Africans would earn their freedom. However, Laurens’ most significant accomplishment was helping convince France to lend their ships to the Americans for the siege of Yorktown.

Laurens was born on Oct. 28, 1754, in Charleston, South Carolina, to Eleanor Ball and Henry Laurens. John enjoyed a privileged life growing up. Henry Laurens made his fortune in the slave trade and his rice plantation. He was also active in continental politics, serving as both a member and President of the Continental Congress. After Eleanor’s death, Henry moved John and his three brothers to Switzerland to further the boy’s education. Two years later, John moved to England to continue his legal studies.

Laurens married Martha Manning in London on Oct. 26, 1776. Her father, one of Henry Laurens’s business agents, was a mentor and family friend whose home Laurens had frequently visited during his years in London. Laurens and Manning’s daughter, Frances Eleanor Laurens, was born around January 1777. Laurens’ father-in-law wrote to him that the infant had “undergone much pain, & misery by a swelling in her hip, & thigh, I believe from a hurt by the carelessness of the nurse.” Frances was not expected to live, but by July 1777, she had recovered from a successful hip surgery.

Despite studying law, Laurens was more interested in the tensions between the colonies and England. Laurens left England by 1777 and returned to America via France. He joined the Continental Army later that year, and Laurens subsequently participated in the Battle of Brandywine. Washington chose Laurens to serve as one of his aides due to his fluency in French. Laurens formed friendships with other members of Washington’s inner circle during the war, including Alexander Hamilton and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Laurens was an idealist. He believed the republic the Americans were fighting for meant nothing if they relied on slave labor. Anti-slave writings released in England while Laurens was studying inspired him. He encouraged those around him, including Washington, to consider freeing their enslaved workers. Laurens received mixed responses to his proposals. Some, such as Lafayette, came to the same conclusion. Others, such as Washington, remained hesitant, fearing the economic and social chaos such a move would cause.

By 1778, Laurens had taken his abolitionist beliefs a step further. He proposed the recruitment of a unit of enslaved men from the South. Once they finished their military service, they would gain their freedom. The Continental Congress considered the proposal, believing that the British were already putting a similar plan into action. The first time this plan was considered, it was rejected, but when the plan came under discussion again in 1779 as the British forces moved south, it was accepted. However, the assemblies of South Carolina and Georgia had to agree to the acceptance of the plan. Laurens left to assist with the defense of South Carolina during this period, hoping to raise his proposed regiment while there. Unfortunately, the states rejected Laurens’ plan, and the regiment was never formed.

Laurens spent the next three years working to improve the Continental Army’s defenses. He still suffered setbacks, though. The British captured Laurens in May 1780, after Charleston fell to them. The British shipped Laurens to Philadelphia, where they paroled him under the condition that he would not leave Pennsylvania. A prisoner exchange freed Laurens in November 1780.

After his return, Laurens was asked to act as a special ambassador to France. He was originally against the idea of being the ambassador because he wanted to take part in the war’s southern campaign. He also believed Hamilton was a better candidate for the role. Hamilton and Congress eventually convinced Laurens to accept the role, and he was officially appointed in December 1780. In March 1781, Laurens arrived in France along with fellow special ambassador Thomas Paine. Their task was to help Benjamin Franklin, who had been serving as the American ambassador in Paris since 1777. The trio met with King Louis XVI and other French military leaders. Thankfully, the French promised a fleet of ships would support the American war effort that year. This agreement proved fruitful, and Laurens returned from France in time to see the French fleet arrive at New York. He then joined Washington in Virginia during the siege of Yorktown. The French fleet ultimately ensured the British troops’ surrender on Oct. 17, 1781. Washington placed Laurens in charge of creating formal terms for the surrender. Laurens then returned to Charleston, South Carolina under the command of General Nathanael Greene. He led a spy network that tracked British operations in and around Charleston.

During the war, Laurens’ friends and comrades viewed him as reckless in battle. This behavior had deadly consequences, leading Laurens to sustain injuries in every battle he fought. His rashness finally caught up with him. He died during the Battle of the Combahee River, in South Carolina on Aug. 27, 1782. Laurens was one of the last Soldiers to die during the war. Despite his untimely passing at age 27, Laurens was fondly remembered by the people who knew him best. Close friend Hamilton wrote to Greene, “I feel the loss of a friend whom I truly and most tenderly loved, and one of a very small number.” Greene subsequently replied: “The army has lost a brave officer and the public a worthy citizen.”

Laurens was unusual for someone born in what would one day be the southern states. He believed liberty and freedom, helped by slavery, did not deserve to be called either. Laurens pioneered abolitionism in the South, inspiring future abolitionists when the movement became more prominent. Additionally, Laurens played a crucial role in getting the needed French assistance for the siege of Yorktown. His ability to convince France to lend their aid led to a crucial turning point in the war, as the defeat of the British at Yorktown helped to start negotiations to end the war. Two centuries after Laurens’ death, his beliefs and accomplishments are still discussed and celebrated.

Lane Gooding

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

“Army Correspondence of Col. John Laurens.” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine. October 1901.

Fitzpatrick, Siobhan. “John Laurens.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/john-laurens/.

Laurens, John. “To Alexander Hamilton from Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens, 18 December 1779.” Founders Online. National Archives. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0546.

“Lt Colonel John Laurens.” National Park Service. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://home.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/johnlaurens.htm.

Massey, Gregory D. “Slavery and Liberty in the American Revolution: John Laurens’s Black Regiment Proposal.” Varsity Tutors. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.varsitytutors.com/earlyamerica/early-america-review/volume-1/slavery-liberty-american-revolution.

Wallace, David Duncan. The Life of Henry Laurens: With a Sketch of the Life of Lieutenant-Colonel John Laurens. New York: Russell & Russell, 1915.

Wheeler, Daniel. Life and Writings of Thomas Paine, Volume 1. Vincent & Parke, 1908.

Additional Resources

Clary, David A. Adopted Son: Washington, Lafayette, and the Friendship That Saved the Revolution. New York: Bantam Books, 2007.

Lefkowitz, Arthur S. George Washington’s Indispensable Men. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2003.

Massey, Gregory D. John Laurens and the American Revolution. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

Rakove, Jack. Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

The Army Correspondence of Colonel John Laurens in the Years 1777-8. The New York Times & Arno Press, New York, New York, 1969.

Townsend, Sara Bertha. An American Soldier: The Life of John Laurens. Edwards & Broughton Company, Raleigh, North Carolina, 1958.