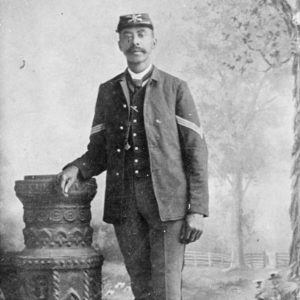

John Denny

Sergeant

9th Cavalry

1846-November 26, 1901

Sgt. John Denny. Library of Congress.

Under the blistering desert sun with bullets and arrows raining down from the canyon walls, Sgt. John Denny spotted a fellow Soldier lying wounded near his position. Denny abandoned his cover, sprinted to the wounded Soldier and brought him back to friendly lines. One of three Soldiers to be awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Las Animas Canyon, Denny exemplified the exceptional courage and tenacity of the 9th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers. Denny, and others of the 9th and 10th Cavalries, proved to their country that African American Soldiers embodied the highest ideals of bravery and valor.

John Denny was born in the town of Big Flats, New York in 1846. His family owned a 75-acre tobacco farm and Denny grew up working in the family business. When he turned 21, he enlisted at the Army recruitment station in Elmira, New York. With his enlistment, he began a lifetime of military service.

Denny spent his first five years in Kansas and Oklahoma in service with the 10th Cavalry, one of the two regiments composed solely of African American Soldiers, nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers.” From 1811 to 1925, the Army in the West was embroiled in a series of conflicts collectively called the “Indian Wars.” Sparked by several factors including land disputes, raiding parties, and white settlers’ murders of Native Americans, the U.S. government gave the Army orders to relocate Native populations to designated, federally subsidized reservations, by force if necessary.

Denny and the 10th participated in campaigns against the Northern Cheyenne, Apaches, and other affiliated tribes during the Indian Wars. The 10th Cavalry prevented the Cheyennes from fleeing north which allowed Lt. George Armstrong Custer and his cavalry to catch up and defeat the Cheyenne in battle. Denny then transferred to the 9th Cavalry with whom he spent the rest of his service.

In September 1879, Denny and Troop C, 9th Cavalry were in pursuit of Chief Victorio, an Apache chief who opposed the U.S. government’s relocation of his people to a reservation in Arizona. The U.S. government had previously assured Victorio and his Warm Springs Apache that they could remain in their ancestral homelands in New Mexico. The government then reversed that decision and began consolidating all Apaches onto a single reservation in the Arizona desert. Negotiations over the location of the reservation broke down and erupted in violence, leading Victorio and 80 of his people to flee in fear of retaliation. For the next three years, the 9th and other regiments pursued the Warm Springs Apache in an attempt to return them to the Arizona reservation.

In 1879, the 9th followed Victorio’s trail to Las Animas Canyon, New Mexico. There, they encountered a group of Apache warriors hiding in wait. In the ensuing ambush, the 9th took heavy fire as they crouched in the valley, unable to rebuff the 150 Apache firing from the canyon walls. Denny’s commanding officer ordered the troop to retreat. As the men prepared to fall back, Denny spotted Pvt. A. Freeland wounded and unable to move. Risking his own life, Denny ran to Freeland’s side and successfully moved him to safety, despite withering fire. The 9th retreated and fell back to a more defensible position, and in the weeks following the battle, the 9th continued their pursuit of Chief Victorio. Thanks to Denny’s actions, Freeland survived and returned to his unit following his recovery.

It took 15 years, but Denny was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Las Animas in 1894. Sources are conflicted on why there was such a long delay in the award’s presentation. Members of Troop C recalled that Denny did not feel he deserved a medal for doing his Soldier’s duty and had asked his commanding officer not to expedite the paperwork. Another source mentions that the paperwork for the medal may have gotten lost until members of Troop C reissued their nominations 12 years after Las Animas. Whatever the reason, Denny’s actions were ultimately recognized as examples of valor and sacrifice worthy of the nation’s highest military award.

Denny continued to serve with the 9th Cavalry until his retirement in 1897. He remained in Nebraska at Fort Robinson, his last assignment, where he worked at the Post Exchange. Due to ill health, Denny moved to Washington, D.C. in 1899 to recuperate at the Soldiers’ Home (now the Armed Forces Retirement Home). He lived there until his death in 1901 and is buried at the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Megan Willmes

Education Specialist

Sources

Dworkin, Rachel. “John Denny and the Buffalo Soldiers.” Chemung County Historical Society. February 4, 2013. http://chemungcountyhistoricalsociety.blogspot.com/2013/02/john-denny-and-buffalo-soldiers.html.

Evans, Max. Faraway Blue. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2005.

National Parks Service. “John Denny.” Last modified June 4, 2018. https://www.nps.gov/people/john-denny.htm.

How Sleep the Brave. “The Legacy of African American Military Service.” Last modified December 9, 2017. https://ussahcemetery.wordpress.com/soldiers-home-national-cemetery/buffalo-soldiers-the-legacy-of-african-american-military-service/.

Schubert, Frank N. “The Apache Wars, 1877-1879.” Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Honor, 1870-1898. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Pub., Inc., 2009.