Henry Knox

Major General

United States Army

July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806

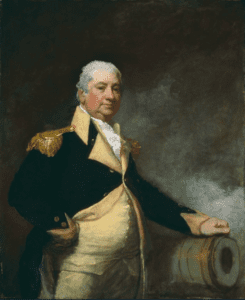

Portrait of Henry Knox by Gilbert Stuart, 1806. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Maj. Gen. Henry Knox boasts one of the most compelling experiences of the American Revolution. A bookseller by trade, Knox became a senior officer of the Continental Army. After the war, he put his military experience to use as the first U.S. secretary of war under President George Washington.

Born in Boston in 1750 to Scots-Irish immigrants, Knox received a rigorous education at the Boston Latin School. He was forced to abandon his education at age 9 when his father left for the West Indies and died of unknown causes. As the oldest son, Knox found work as a clerk in a bookstore to financially support his family. However, the young boy found a father figure in the store’s owner, Nicholas Bowes, who vested Knox with a love of reading and learning. In between shifts, the future Soldier taught himself French, philosophy, and mathematics, and found himself captivated by the military campaigns of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

As a teenager, Knox joined one of Boston’s gangs and earned a reputation as a strong and capable street fighter. After witnessing the local militia parade through Boston in honor of King George III’s birthday, Knox decided to enlist. He joined a company of artillery known as The Train under the command of Lt. Adino Paddock, a Boston Tory. A quick learner, Knox gained valuable experience and knowledge of artillery during his time with The Train.

By 1770, Knox found himself swept into the tumultuous political tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain. On March 5, he witnessed British troops open fire on a colonial mob in what became known as the Boston Massacre. Knox desperately tried to diffuse the situation by encouraging the mob to disperse and pleading with the soldiers to return to their barracks. He testified at the soldiers’ subsequent trial, in which all but two were acquitted.

In 1771, Knox opened his own bookstore in Boston. The London Book Store, as Knox called it, served as a popular shopping destination for the city’s elite, aristocratic residents. The young store owner kept a large inventory of military history and strategy books and enjoyed chatting with soldiers who frequented the shop. In 1772, he pursued his martial aspirations by founding the Boston Grenadier Corps, an offshoot militia organization from The Train. He also acquainted himself with the Sons of Liberty, performing guard duty on their behalf before the Boston Tea Party in 1773.

The following year, Knox began courting Lucy Flucker, the daughter of one of Boston’s most prominent loyalist families. They wed on June 16, 1774, despite her father’s disapproval. Lucy’s brother served in the British army, and through his influence Lucy’s father offered Knox an officer’s commission. However, Knox’s Patriot convictions ran deep, and he refused. When the war broke out at Lexington and Concord, the couple fled Boston. Lucy’s parents remained staunchly loyal to the crown and promptly disowned her after she chose to side with her husband. Knox quickly joined the militia army besieging the city where he demonstrated his engineering skills by developing fortifications and directing artillery fire at the Battle of Bunker Hill. When Gen. George Washington assumed command of the newly organized Continental Army, he chose Knox to lead the Army’s artillery regiment, while John Adams (a former patron of Knox’s bookstore) lobbied the Second Continental Congress to promote the young officer to colonel, which they did in July 1775.

As the Siege of Boston wore on, Knox suggested that Washington send an expedition to retrieve cannons and supplies at the recently captured Fort Ticonderoga, New York. The commanding general agreed, and placed Knox in command of the expedition. He reached Ticonderoga on Dec. 5 and began a 300-mile trek back to Boston, hauling nearly 60 tons of cannons and other munitions across the icy Berkshire Mountains. Knox returned with the guns on Jan. 27, 1776, just in time to deploy them on Dorchester Heights and bombard the city. The galling fire from Knox’s guns compelled the British army and navy to withdraw to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Col. Knox continued to serve as Washington’s chief of artillery through the New York and New Jersey campaigns. As British troops landed at Kip’s Bay, Knox rode to the front to rally the retreating Continental Soldiers, determined to make a stand. However, Col. Aaron Burr arrived and assured them that a way of escape was still possible along the Bloomingdale Road. Burr led the troops in a withdrawal, while Knox remained behind to ensure all the Continentals made it to safety. Then he escaped on a boat up the East River to Harlem. He was greeted by Washington, who had thought him lost.

In December 1776, Washington placed Knox in charge of logistics for the crossing of the Delaware River before the Battle of Trenton. He ferried 18 guns across the river and used them to great effect against the Hessians. Knox received a promotion to brigadier general for his performance during the Delaware crossing and Battle of Trenton. He led the Army across the river several days later for the Battle of Assunpink Creek and the Battle of Princeton.

In 1777, Knox returned to Massachusetts to bolster the Army’s artillery supply. He oversaw the production of guns at Springfield as well as raised a new battalion of artillerymen. In June, Congress appointed the Frenchman Philippe Charles Tronson du Coudray to command the Army’s artillery, an appointment intended to improve relations with France. Insulted by the oversight, Knox tendered his resignation, while Washington, Gen. Nathanael Greene, and Gen. John Sullivan petitioned Congress on his behalf. They succeeded in persuading Congress to reassign Du Coudray as inspector general.

Knox continued to serve through the Philadelphia Campaign. At the Battle of Germantown, he made a critical error in ordering the Army to capture the Chew House, a stone mansion occupied by the British army as a stronghold. This decision resulted in a crippling delay in the Army’s advance, allowing the British time to reorganize. However, Knox redeemed himself at the Battle of Monmouth the following year, where Washington credited the artillery with preventing a disastrous defeat.

During the winter encampment of 1778-79, Knox established the Continental Army’s first artillery and officer training school, a predecessor to the United States Military Academy at West Point. The young general trained over 1,000 Soldiers in unforgiving conditions; the Army lacked adequate supplies during that winter. In September 1780, Knox served on the tribunal that convicted British Maj. John Andre, who assisted in the defection of Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold. The following year, Washington moved the Continental Army south to corner Gen. Charles Cornwallis’s British army at Yorktown, Virginia. Knox collaborated with the French chief of artillery, Lt. Col. Comte d’Aboville, to oversee the placement of guns during the Siege of Yorktown.

Between Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown and the Treaty of Paris in 1783, Knox continued to serve his fledgling nation. He was promoted to major general in 1782 and assisted Congressman Gouverneur Morris in negotiating prisoner exchanges with the British. After those negotiations failed, he rejoined the Army at Newburgh, New York and began inspecting the fortifications at West Point, which he deemed a critical defensive position. After enduring the death of his 9-month-old son, Knox devoted himself to lobbying Congress to raise military pensions. He fiercely defended Washington during the Newburgh Conspiracy as rumors of mutiny swirled about the Army.

Following peace in 1783, Congress moved to demobilize the Continental Army, but Washington granted Knox command of what troops remained. That same year, he was also a founder of the Society of the Cincinnati — a fraternal organization of former Revolutionary War officers that persists to this day. As commander in chief of the Continental military, Knox drafted plans for a peacetime Army as well as two military academies, one for the Navy and one for the Army.

After the final British troops withdrew from New York, Knox resigned his commission in the Army. However, Congress appointed him secretary of war in 1785, an offer which he could not refuse. In this position, Knox championed the idea of a peacetime Army and battled opposition in Congress, some members of which feared it could become a weapon of the state. When Washington was elected president in 1789, he retained Knox as his secretary of war. As the civilian leader of the nation’s military, Knox negotiated with Indian nations and called for recognizing their sovereignty. However, he struggled to police illegal settlements and land purchases on Indian territories. He resigned from Washington’s cabinet in 1795 and settled in the District of Maine. On Oct. 22, 1806, Knox swallowed a chicken bone that lodged in his throat and caused an infection. He died three days later on Oct. 25 at age 56. He was buried on his estate in Thomaston, Maine.

While Knox is remembered most for his skillful transport of the guns from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston, his legacy extends well beyond the Revolutionary War and the founding of the nation. He sits among the likes of Washington and Greene as heroes of the Revolutionary era. Numerous towns, cities, and military installations bear his name — most notably Fort Knox, Kentucky.

Evan Portman

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

Brooks, Noah. Henry Knox: A Soldier of the Revolution. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900.

Drake, Francis S. Life and Correspondence of Henry Knox: Major General in the American Revolutionary Army. Boston: Samuel G. Drake, 1873.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, USA, 2005.

Hamilton, Phillip. The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

Puls, Mark. Henry Knox: Visionary General of the American Revolution. New York: St. Martin’s Press, LLC., 2008.