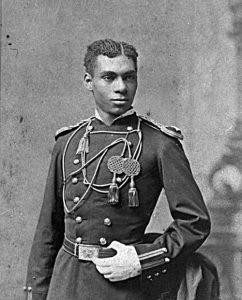

Henry O. Flipper

Second Lieutenant

10th Cavalry Division

March 21, 1856-April 26, 1940

2nd Lt. Henry O. Flipper. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Military Affairs.

Born into slavery, Henry O. Flipper fought his way through prejudice and isolation to become the first African American graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point and first commissioned Black officer in the U.S. Army. He fought with distinction in the Indian Wars before a court-martial found him guilty of conduct unbecoming after commissary funds went missing on his watch. Flipper spent the rest of his life in the Southwest, becoming an expert on property law, a mining engineer, Spanish translator, writer, and assistant to the Secretary of the Interior before his death in 1940.

Henry O. Flipper was born to enslaved parents in Thomasville, Georgia in March 1856. His parents were enslaved by different men when his father’s enslaver decided to move to Atlanta. Flipper’s father used all his savings to successfully beg his enslaver to buy his son and wife so they could remain together. Following the Civil War, Flipper’s family remained in Atlanta and Flipper entered the newly-established Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University) in 1869.

Flipper, as he later wrote in his memoirs, always aspired to become a Soldier for the United States Army. In 1873 he wrote to Congressman James Freeman asking for his recommendation to be appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Flipper succeeded in securing his appointment and entered West Point later that year. Despite enduring almost total social isolation while at West Point, Flipper persevered. In 1877, he became the first African American to graduate from West Point and the Army’s first African American officer.

Flipper was commissioned as a second lieutenant and left for Oklahoma. He joined the 10th Cavalry, one of only two units composed of African American Soldiers and nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers.” The unit had already won renown for its Soldiers’ bravery in the Indian Wars when Flipper joined them at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Flipper proved a capable engineer, building roads and telegraph lines from Gainesville, Texas to Fort Sill. He also engineered a system to drain several ponds blamed for causing malaria. The drainage system, known as “Flipper’s Ditch,” is still in use today and is registered as a National Historic Landmark.

The 10th Cavalry was reassigned to Fort Concho, Texas in June 1880. Two weeks after his arrival, Flipper and the 10th Cavalry were sent out into the field to fight Chief Victorio and his Apache warriors. In recognition of his achievements, Flipper was assigned as assistant quartermaster at Fort Davis, Texas where he was responsible for food inventory, distribution, and keeping track of the commissary’s financials. In the summer of 1881, Flipper discovered a $3,000 discrepancy in the commissary funds. Knowing he would be blamed for the missing money, he attempted to conceal the loss until he could repay it from his own pocket. His commanding officer found out about the missing money, however, and Flipper was court-martialed. The court found him guilty of “conduct unbecoming an officer” and dishonorably dismissed Flipper from the Army in 1882.

With his military career finished, Flipper decided to remain in the Southwest, serving as a Spanish translator and becoming an expert in land rights and property law. He worked with the Department of Justice’s Court of Private Land Claims for eight years, surveying land grants and appearing as a government witness in several court cases. He worked with two Mexican mining companies and moved to El Paso, Texas, in 1912. During Mexico’s civil war, Flipper supplied information on conditions in the country to the U.S. Senate’s subcommittee on Mexican affairs. Due to his expertise, Flipper became special assistant to the Secretary of the Interior from 1921 to 1923, when he left for Venezuela to serve as a mining engineer. He returned to the U.S. in 1930 and retired a year later to Atlanta, Georgia. Flipper lived there until his death from a heart attack in 1940.

During his life, Flipper wrote and translated several works on mining, engineering, history, and property law, including two memoirs, “The Colored Cadet at West Point (1878)” and “Negro Frontiersman: The Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper (1963)”. Both of these works are the only depictions of life as an African American on the frontier and are indispensable historical sources.

Flipper attempted to regain his commission in the Army multiple times, including during the War with Spain, but was ultimately unsuccessful. It wasn’t until 1976, nearly 36 years after his death, that a review of his case declared the punishment Flipper received to be “unduly harsh.” The Army corrected Flipper’s records to show an honorable discharge and President Bill Clinton pardoned Flipper in 1999.

Megan Willmes

Education Specialist

Sources

Dinges, Bruce J. “Flipper, Henry Ossian,” Handbook of Texas Online, Accessed December 26, 2020. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/flipper-henry-ossian.

Harris, Theodore D. “Flipper, Henry Ossian.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=FL002.

U.S. Army Center of Military History, “Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper.” Last modified January 31, 2021. https://history.army.mil/html/topics/afam/flipper.html.

National Archives and Records Administration. “Lt. Henry O. Flipper.” Last modified March 7, 2017. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/henry-flipper.

National Parks Service. “Second Lieutenant Henry Flipper.” Last modified February 24, 2015. https://www.nps.gov/foda/learn/historyculture/secondlieutenanthenryflipper.htm.