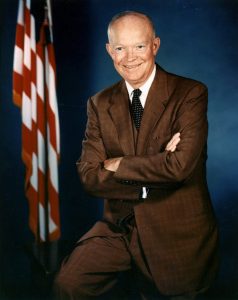

Dwight David Eisenhower

General of the Army

Supreme Allied Commander, Allied Expeditionary Forces

October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, July 1956. Public Domain

Dwight D. Eisenhower began his career in the U.S. Army on June 14, 1911 as a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. As a young officer, his ability to understand military strategy was noticed by high-ranking officials. During World War II, he rose through the ranks to become the Allied Supreme Commander and five-star General of the Army, orchestrating the June 6, 1944, D-Day landings at Normandy, France. After World War II, Eisenhower was elected the 34th President of the United States and served two terms from 1953-61. Despite the outward appearance of two enormously successful careers, Eisenhower’s life is truly representative of the phrase of “not getting what you want, but what you need.”

Dwight David Eisenhower was born on Oct. 14, 1890, in Denison, Texas, to David and Ida Eisenhower. The family moved to a small, three-acre farm in Abilene, Kansas, when he was 2 years old. Despite the family’s lower-class economic situation, Eisenhower and his five brothers were each allotted a small portion of the field to grow their own crops for personal spending money. All six boys learned the necessity and value of hard work through the sales of their crops.

Eisenhower and his older brother, Edgar, dreamed of going to college—a dream that the family could not afford. Eisenhower offered to take on extra work for a year to help pay for Edgar’s tuition, on the condition that his brother would take a break from college to return the financial favor. Eisenhower held true to his word and sent Edgar $200 that first year. During this time, Eisenhower learned that he could attend college tuition-free through military service. He applied for his top choice, the Naval Academy, but was rejected because he was over the age of 20. Although he was disappointed, he did not give up. He persisted in achieving his educational goal by applying to the United States Military Academy at West Point and was accepted.

After graduating from West Point in 1915, he was stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. While on guard duty, he met the vivacious socialite Mary Geneva Doud, known as Mamie. Soon after he received the Doud family’s blessing to marry Mamie, he had more great news to share: his application to transfer into the Aviation section of the Army was approved. Unfortunately, the Doud family did not share in Eisenhower’s happiness. In the early 20th century, flying was still considered risky and the Doud family was concerned that Mamie would end up a young widow. The Doud family gave him an ultimatum: he could marry the girl of his dreams or pursue the career of his dreams. He chose Mamie.

Mamie and 1st Lt. Dwight Eisenhower, 1916. U.S. Army

Although he gave up the opportunity to fly airplanes, he continued to yearn for a more exciting career. In April 1917, the United States entered World War I. Eisenhower was eager to join the fight overseas. His repeated applications to combat units were denied. He was assigned to a tank battalion at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, where he formed a close friendship with Capt. George S. Patton, Jr. Finally, in October 1918, Eisenhower received mobilization orders. Before Eisenhower could get the chance to leave the States for war, Germany agreed to an armistice that ended World War I on Nov. 11, 1918. The Versailles Peace treaty would be signed on June 28, 1919. Disappointment settled in as his colleagues, friends, and West Point acquaintances returned home with promotions and medals.

The following year, in 1919, he embarked on a cross-country convoy to gauge the Army’s transportation and logistical capabilities. He reported on the road conditions, equipment capabilities, and discipline factors between officers and enlisted men. In 1922, he was stationed at Camp Gaillard in the Panama Canal Zone. The camp’s conditions were less than ideal for his family, but the assignment was the perfect opportunity for Eisenhower to serve with Brig. Gen. Fox Connor. Connor held significant influence over the young officer, awakening a deep interest in military history and strategy. He convinced Eisenhower that the conditions surrounding the Treaty of Versailles would lead to a new European war within 20 years. His mentorship directly contributed to Eisenhower’s academic success at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1925, and later at the Army War College in 1928 in Washington Barracks, Washington D.C. (now Fort Lesley J. McNair).

After graduating from the Army War College, he was given two choices. He could have an assignment on the General Staff working with the Army Chief of Staff Charles Pelot Summerall, or he could travel to France to study the World War I battlefields and edit associated military guidebooks. Eisenhower wanted the assignment on the General Staff. He believed it would enhance his career. However, his wife, Mamie, wanted to spend time abroad. In the end, he gave up what he wanted and chose to study the battlefields in France. Through studying French geography, Eisenhower became familiar with nearly all aspects of the country’s transportation system: from landscape to roadways to rail system.

During the 1930s, German aggression built up, culminating in the invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939. As a result, France and England declared war on Germany. The United States entered the war in 1941 after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. During World War II, Eisenhower was sent to Europe to help develop the campaign against the Axis powers. Faced with juggling personal inputs from world leaders like President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill with those of Allied generals, Eisenhower found that Connor’s tutelage had given him the ability to combine and execute political and military objectives. Among the top Allied European field commanders were men from his past, including West Point classmate General Omar Bradley, and now-General Patton.

The British were fighting Italian and German forces in North Africa by the time Eisenhower was sent overseas. He worked with British commanders, including Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, and navigated through the complicated loyalties of the French military leaders (some supported the Nazi regime and others supported the Allies). He planned Operation Torch, which called for an invasion of the French colonies in northern Africa in November 1942. The campaign was a success, and President Roosevelt wanted to award the Medal of Honor to Eisenhower for his planning efforts. Eisenhower refused, insisting that the medal was for heroism displayed during combat and that he was unworthy of such an honor. He was promoted to Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Forces in December 1943.

General Dwight Eisenhower, Feb. 1, 1945. U.S. Army

Although the Allies began to show signs of winning the war on the Eastern European front by 1943, the German army still occupied all of western Europe. The Allies would need to invade and liberate western Eurpope and take pressure off of the Soviets fighting the Germans on the eastern front. Eisenhower worked closely with Bradley to orchestrate the air, land, and sea invasion of Normandy that took place on June 6, 1944. This invasion is also known as Operation Overlord. Eisenhower’s experience from the cross-country convoy in 1919 provided invaluable logistic insight as he moved men and equipment across North Africa and Europe. Additionally, the in-depth study of the World War I French landscape gave him the advantage of providing alternate routes of attack in driving the Germans out of occupied France.

Eisenhower’s reputation for connecting with the troops, along with ensuring the enlisted men were given the same morale amenities as officers, earned him widespread respect among Soldiers. When he learned that the Italian island of Capri had been designated only for officers to enjoy Rest & Recuperation (R&R), he demanded that equal opportunity be given to the enlisted men, stating, “This is supposed to be a rest center—for combat men—not a playground for the Brass!” He led by example in small ways, too. During the war, food and cigarettes were rationed out among the Soldiers. If a Soldier ran out of cigarettes, they would have to wait until the next supply of rations came in. Eisenhower held himself to the same standard and rolled his own cigarettes when he ran out. He also made a personal effort to connect with the troops. After giving the final approval of the D-Day invasion of Normandy, Eisenhower visited the paratroopers in Newbury, England, on June 5, 1944, while they geared up for the invasion. He asked them questions and shook their hands. He then stayed to watch the planes depart. In his pocket was a piece of paper that he wrote and signed, accepting complete responsibility if Operation Overlord failed.

By the time World War II ended, Eisenhower was popular throughout the United States. Three years after the war ended, he stepped back from the military spotlight to become president of Columbia University in New York. In 1950, the United States became involved in the Korean War. Many Americans believed Eisenhower could bring a swift end to the war and encouraged him to run for president of the United States. In 1952, he officially declared his intention to run on the Republican ticket. He won the election and was inaugurated as the 34th president of the United States.

He served as president for two terms, between 1953-61. The diplomacy he learned from dealing with world leaders during World War II, along with his military strategic mindset, guided his decisions as a president. The experiences he gained as Allied Supreme Commander prepared him to evaluate international conflicts. He recognized that the Korean War battles would continue to perpetuate a stalemate, and advised against investing more American troops and equipment to the conflict. Seven months after his inauguration, an armistice was signed between North and South Korea. In 1954, when France asked for extensive military support in their fight against Vietnam, Eisenhower viewed the situation with a military strategic mindset and declined their request.

Nuclear power, initially used against Japan to end World War II, became a source of conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States. The tension between the two countries, and the desire to possess nuclear superiority, developed into the Cold War. Eisenhower understood nuclear power was vital to national security, but was wary of its use as a weapon. Instead, he hoped it could be used as a source of energy, with power equally distributed among the nations. In 1957, the International Atomic Energy Agency was created.

Eisenhower’s experience in the cross-country military convoy of 1919 became a factor in advocating for an improved transportation system in the United States. Until 1956, individual states were responsible for establishing and maintaining the roads. This meant that not all states were easily connected by well-maintained roads. Eisenhower proposed a new system in which the federal government would design and fund highways that would run across the state borders. On June 29, 1956, he signed the Federal Aid Highway Act that established the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System and expanded the construction, and connection, of roads within the United States. During his presidency, he also signed bills approving the creation of the National Aeronautical and Space Administration, and the induction of Hawaii and Alaska as states. After his second term, he retired to his home near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. His advice was still sought by presidents after him. Eisenhower died on March 28, 1969.

He was born into a humble family, and felt the impact of the disparity between social classes early in his life. He might have wished for wealthier circumstances, but his childhood experiences influenced his determination to provide equal morale opportunities for both enlisted personnel and officers during World War II. The war was tough, and ensuring support for the Soldiers was crucial. His rejection by the Naval Academy left him utterly disappointed, yet propelled him into a better, brighter future than he could have imagined—one that introduced him to his wife of 53 years, a position that directly impacted the end of a major world war and propelled him to the presidency of the United States. Each moment in his life pivoted him from what he wanted while preparing him to take on bigger and greater challenges.

His legacy lives on in the numerous schools, parks, scholarship foundations, and buildings named after him. The United States interstate highway system is often referred to as the Eisenhower Interstate System. His presidential library and museum is located in his hometown of Abilene, Kansas. In 2023, the Army base formerly known as Fort Gordon, located in Augusta, Georgia, was redesignated as Fort Eisenhower in his honor.

Katie Roxberry

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

Ambrose, Stephen. Ike: Abilene to Berlin. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1973.

American Heritage Magazine and United Press International, ed. Eisenhower American Hero, The Historical Record of His Life. American Heritage Publishing Co, Inc., 1969.

Carpenter, Ronald H. “General Eisenhower: Ideology and Discourse.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 7, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 237-241. https://muse-jhu-edu.proxygw.wrlc.org/article/173955.

Carter, Donald Alan. “Eisenhower Versus the Generals.” The Journal of military history 71, no. 4 (2007): 1169–1199. https://muse-jhu-edu.proxygw.wrlc.org/article/222498.

D’este, Carlo. Eisenhower, a Soldier’s Life. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2002.

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, & Boyhood Home. “Chronologies.” The Eisenhowers. https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/eisenhowers/chronologies.

Perret, Geoffrey. Eisenhower. New York: Random House Publishing, 1999.

Scammell, Joseph M. “General Eisenhower as Supreme Commander.” Military Affairs. Lexington, Va: The American Military Institute, 1947. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=27390cf2-2238-4e42-8cd0-12e7dc0cdc8d%40redis.

Additional Resources

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, & Boyhood Home https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/.

Eisenhower, D.D. “Report on Trans-Continental Trip.” November 3, 1919. https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/research/online-documents/1919-convoy/1919-11-03-dde-to-chief.pdf.

Uri, John. “65 Years Ago: The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 Creates NASA.” NASA. July 26, 2023. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/65-years-ago-the-national-aeronautics-and-space-act-of-1958-creates-nasa.