Daniel Nimham

Captain

Stockbridge Indian Company

c. 1726 – 1778

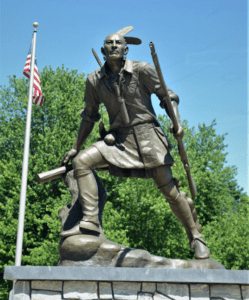

Statue of Daniel Nimham located in Fishkill, New York. Gregorytotino

Capt. Daniel Nimham was a diplomat, a fighter, and the last leader, or sachem, of the Wappinger tribe native to New York’s Hudson Valley. Nimham fought for the British in the French and Indian War but against them in the Revolutionary War. The Continental Army commissioned Nimham as a captain, and he was with General George Washington at Valley Forge. Nimham later gave his life for the American cause. Nimham’s actions helped to create the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, and Native Americans still living in the Hudson Valley continue to honor his memory.

Before 1609, the Wappinger People lived on the eastern shore of the Hudson River in New York. To the Wappingers, it was the Muhheakantuck, “the river that flows both ways,” and their territory spread from Manhattan Island north to the Roeliff Jansen Kill in Columbia County, and east as far as the Norwalk River in Fairfield County, Connecticut. The Wappingers were allied with the Mohican People to the north. Their settlements included camps along the major creeks and Hudson River tributaries with larger villages located where these streams met the river.

Nimham was born sometime around 1726, when the Wappingers only numbered in the hundreds due to war, disease, and mixing of different tribes in the area. Nimham first encountered European settlers in the mid-1700s, from whom he learned English and maintained a friendly relationship with them. When Nimham grew up, he became the sachem of his people around 1760, specifically leading a small group of 300 displaced Native Americans who wandered the borders between Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. At this point, he had become an experienced warrior and diplomat.

Nimham participated in the French and Indian War, where he and about 300 Wappinger men fought for the British. After the war ended, a rich merchant from New York City named Adolphus Philipse made a claim on Wappinger territory. The land grab angered Nimham and the Wappingers, so the sachem took the issue to the colonial court to take the stolen land back for his people. He had no luck with the colonial courts, so Nimham and some Mohican sachems traveled to England in 1766 to plead their case before King George III’s Lords of Trade. Rent rioters and land speculators who were sympathetic to Nimham paid for the trip. While the Lords of Trade told Nimham he was in the right, the colonial court dropped his case when he returned to the colonies, as the court believed returning the land would set a bad example for similar disputes. The Wappingers felt betrayed by the ruling, as they had fought for the British but gained nothing. On July 4, 1776, the colonies declared independence from Great Britain, with Nimham and his people joining the colonists’ cause for two reasons. First, Nimham saw the value of the Patriot cause of freedom, recognizing that Great Britain had wronged the colonists as well. Second, there was an agreement that Patriot Soldiers would receive land, and Nimham likely assumed that the Native Americans would receive the same rewards.

The Continental Army commissioned Nimham a captain, and he proved to be an essential force for the American cause. Nimham recruited warriors from Native communities stretching from Canada to the Ohio Valley. The Continental Army also gave Nimham’s son, Abraham, command of the 60-man “Stockbridge Indian Company,” based in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The company consisted of Mohicans, Wappingers, Munsee, and other tribes from the area.

When the fighting began, Nimham joined his son’s Stockbridge company militia scouts, and served alongside Washington at Valley Forge. They also fought in the Battles of Saratoga, as well as supporting troops led by the Marquis de Lafayette. Nimham and his forces then served under Virginian Brig. Gen. Charles Scott in 1778. The Stockbridge militia company patrolled the northern border of the British-controlled New York City. The militia’s mission was to gather intelligence on enemy movements. On Aug. 20, 1778, the Stockbridge company ambushed a British force north of New York City, killing one light cavalryman and wounding another. News of the attack spread, and the British assembled 500 British regular troops, Hessians, and Loyalist troops.

On Aug. 31, 1778, the British set a trap for the Stockbridge militia on Courtland’s Ridge. Sighting a group of Hessian forces drew Nimham’s 60 warriors into the open, and Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe’s light infantry hit the militia’s left flank. The enemy surrounded and outnumbered Nimham and his men more than eight to one, but the Stockbridge company fought back in hand-to-hand combat. Simcoe described the scene of the Battle of Kingsbridge, or the Stockbridge Massacre. “The Indians fought most gallantly; they pulled more than one of the Cavalry from their horses.” Simcoe said that Nimham called out to his warriors that “he was old and would stand and die there.” Pvt. Edward Wight, a British light cavalryman, killed Nimham, and Abraham also died in the battle.

American independence was won after Nimham’s death. Washington wrote that the Stockbridge “remained firmly attached to us and have fought and bled by our side; that we consider them as friends and brothers.” Despite this claim, their service did little to improve conditions for the Native Americans following the war. With many Stockbridge men dead, growth was difficult. The survivors and families of the dead were banned from the lands offered to white Patriots, so extreme land pressures continued. This led to the Wappingers seeking refuge in central New York’s Oneida Country. The Wappingers then moved to Michigan Territory after the building of the Erie Canal. This territory makes up current-day Wisconsin. Today, the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians are a recognized Native American nation based in Bowler, Wisconsin. A longstanding powwow ceremony continues in their Hudson Valley homeland, dedicated to the Wappingers’ great sachem Nimham. Nimham is also honored with a memorial and historical marker in the Bronx’s Van Cortlandt Park. The park contains the site on which he fought and died in the Battle of Kingsbridge. A bronze statue of Nimham currently stands in the town of Fishkill, New York, dedicated in a ceremony on June 11, 2022. It stands on the Wappingers’ ancestral land. This further allows Nimham’s legacy to endure into the future.

Lane Gooding

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

“Daniel Nimham.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/daniel-nimham.

“Daniel Nimham: Continental Army.” Hero Cards. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.herocards.us/hero187.

Grumet, Robert S. “The Nimhams of the Colonial Hudson Valley, 1667-1783.” The Hudson River Valley Review. The Hudson River Valley Institute, 81-99.

Keropian, Michael. “Sachem Daniel Nimham.” Michael Keropian Sculpture LLC. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.keropiansculpture.com/daniel_nimham.html.

Additional Resources

Frazier, Patrick. The Mohicans of Stockbridge. Nebraska: Bison Books, 1994.

Maxson, Thomas F. Mount Nimham: The Ridge of Patriots. Texas: Rangerville Press, 2010.

Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. London: Penguin Books, 2006.

Smolenski, John, and Thomas J. Humphrey. New World Orders: Violence, Sanction, and Authority in the Colonial Americas. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Vaughn, Alden. Transatlantic Encounters: American Indians in Britain, 1500-1776. England: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Vitelli, Andrew. “Nimham Memorial Recognizes War Hero.” The Examiner News, August 21, 2013. https://www.theexaminernews.com/nimham-memorial-recognizes-war-hero/.