Battling Segregation and the Nazis

The Origins and Combat History of CCR Rifle Company, 14th Armored Division

By James R. Lankford

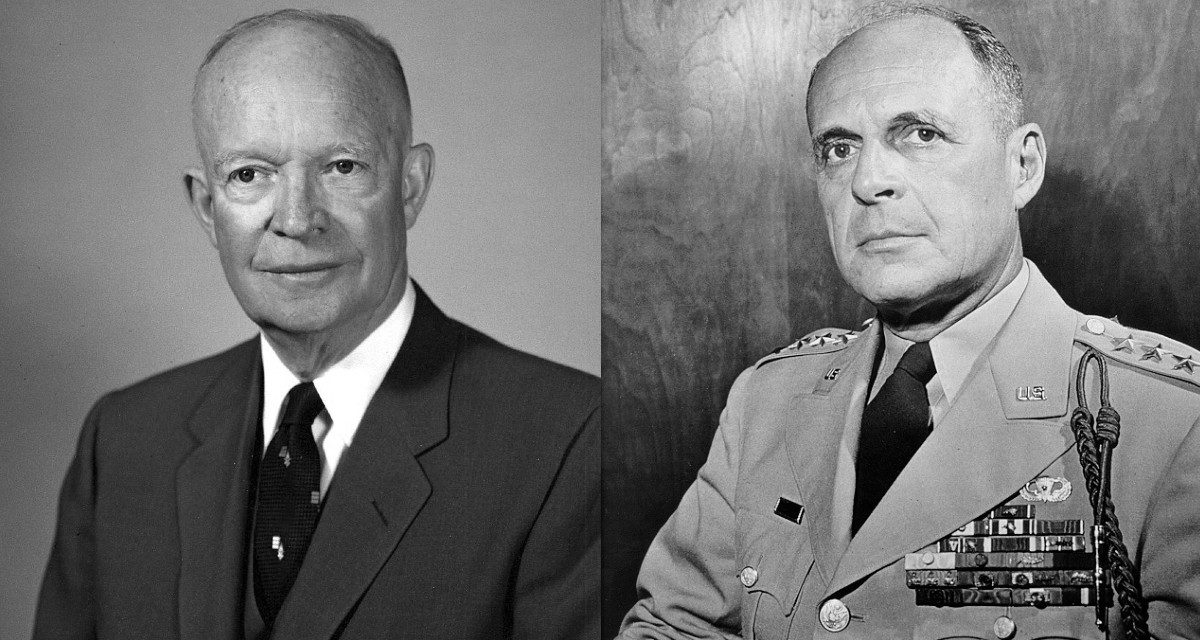

“If you need combat soldiers, and especially if you need them in a hurry, don’t put your time upon Negroes.”1 Retired Maj. Gen. Robert L. Bullard, 1925

“I feel that in existing circumstances I cannot deny the Negro volunteer a chance to serve in battle.”2 General Dwight D. Eisenhower, 7 January 1945

Volunteer African American infantrymen march through Noyon, France, en route to their training area, 28 February 1945

Shortages of Replacement Infantry Riflemen

On 24 March 1945 the 14th Armored Division completed its drive through a heavily defended portion of the West Wall in the Rhenish Palatinate and reached the town of Germershiem, Germany, on the Rhine. Like most of the combat divisions in the European Theater of Operations, the 14th at this point was sorely in need of replacements, particularly infantry riflemen. Three days later, four platoons of hastily trained, replacement infantry riflemen that had been combined to form the Seventh Army Infantry Company Number 4 (Provisional) arrived in the division’s rear area at Altenstadt in northern Alsace, France, and joined the division. Each of the 240 soldiers who stood in this company’s ranks was an African American enlisted man who had volunteered for combat duty as an infantry rifleman.3

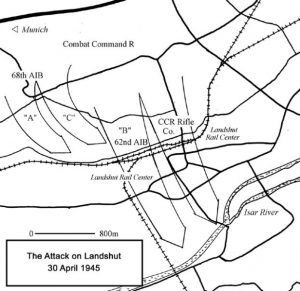

Initially, the new company was attached to the division’s 19th Armored Infantry Battalion (AIB), but division headquarters reassigned the unit to Combat Command R, where it became known as CCR Rifle Company. Although the war against Germany was entering its final phase, the volunteers would have ample opportunity to prove themselves in combat, not only to the enemy, but also to themselves and to their white comrades in arms. CCR Rifle Company served in combat from 1 April to 8 May 1945. Only the severe and growing shortage of infantry riflemen that plagued the American ground forces after the Normandy landings made such an opportunity possible.4

The hard fighting in which the Army engaged in the dense hedgerows of Normandy produced substantially higher losses among infantry riflemen than American military planners had anticipated. The infantry replacements arriving from the United States quickly proved insufficient to compensate for these combat losses, and by the end of July 1944 the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army (ETOUSA), had developed a sufficient shortage of infantry riflemen to ask the War Department for emergency shipments. In November 1944, as American ground forces intensively renewed their efforts to advance into Germany, the number of American casualties, particularly among infantry riflemen, escalated dramatically, and the shortage grew even more severe. Theater strength planners concluded that ETOUSA might have a deficit of more than 53,000 infantrymen, mostly riflemen, by February 1945. Stimulated to action, the theater initiated training courses to convert infantry replacement personnel who were not trained as riflemen to the required specialization, to convert combat personnel in other branches to infantry riflemen, and to retrain selected support personnel and replacements to serve as infantry riflemen. The theater subsequently cut by half or more the training time required to convert other specialties to riflemen. It also urged the War Department to increase the rate at which it was shipping replacement riflemen from the United States but had little success in this endeavor due to the virtual exhaustion of the available manpower pool.5

Despite these efforts, losses continued to exceed the supply of replacements. Once the German Army launched its counteroffensive in the Ardennes on 16 December 1944, the shortage of infantry riflemen quickly reached critical proportions. As the casualty rates soared, so too did the shortage of replacements. A week after the German offensive began, the theater estimated that by the end of the month its combat divisions would be operating with just 78 percent of their authorized rifle strength. The senior officers in the theater, realizing that more had to be done to increase the supply of riflemen, redoubled their efforts to locate and use additional sources of manpower.6

Lt. Gen. John C. H. Lee, commander of the theater’s Communications Zone, recognized that the large number of African American service troops in his command represented a previously untapped source of potential replacements for infantry riflemen. During World War II, the Army assigned most of its black soldiers to service units, influenced substantially by criticism of the combat record in World War I of the 92d Division, one of two comprised of black enlisted personnel. Lt. Gen. Robert L. Bullard, whose Second Army had included the 92d in 1918, believed that the division had failed to fight effectively and concluded, “If you need combat soldiers, and especially if you need them in a hurry, don’t put your time upon Negroes.” In December 1944 General Lee had a very different view. Believing that some of his African American soldiers could usefully contribute to the U.S. Army’s combat effort, Lee suggested to the European theater commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the idea of using volunteers from his black units as replacement riflemen. After further discussion with Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, and the American field army commanders in Europe, Eisenhower accepted Lee’s suggestion, and the Communications Zone began in earnest to develop plans for training black soldiers as infantry riflemen.7

These plans had to be fashioned and defended carefully to avoid being derailed for contravening the Army’s substantial commitment to racial segregation. The White House had in 1940 announced a policy of maintaining the racial segregation of enlisted men in the Army’s regimental organizations, while creating opportunities for African Americans to serve in all major branches of the Army. During World War II, however, the Army activated only three divisions with black enlisted personnel. The Army initially organized the 2d Cavalry Division with a balanced mix of black and white Regular Army horse cavalry regiments but subsequently split up the division and reconstituted it with all black enlisted personnel. Finding no use for horse cavalry in battle, the Army inactivated this division in North Africa in 1944 and sent its black personnel to service and engineer units. The Army also used black enlisted personnel to form the 92d Infantry Division, which served in the Mediterranean Theater, and the 93d Infantry Division, which served in the Southwest Pacific. Since no divisions with African American enlisted personnel were assigned to the European Theater, General Eisenhower realized that black infantry riflemen in his theater would, by necessity, be assigned to white combat divisions.8

While the bulk of his American forces continued the costly struggle in the Ardennes, Eisenhower faced another crisis nearly 100 miles away in northeastern France. There, during the waning hours of 31 December 1944, the German Army initiated a fierce 25-day battle in Lorraine and Alsace when it launched Operation NORDWIND, opening the last major German offensive of the war against the thinly spread lines of the Seventh Army.9 Thus as 1945 began, all three army groups under Eisenhower’s control were engaged in heavy fighting defending large portions of a broad front. On 7 January 1945 Eisenhower wrote to the Combined Chiefs of Staff that “we must expect” the Germans to launch additional attacks. “It is imperative,” Eisenhower wrote, “that we meet this all out German effort by an all out effort of our own. To meet this possible eventuality drastic steps are being taken in this theater: (a) To comb out personnel from the Communications Zone, Lines of Communications units, and Army Air Forces and to train these personnel as replacements for combat units, (b) To convert units which are the least essential to our requirements, (c) To make the maximum use of liberated manpower, both for combat and rear area duties . . .” Beyond his own efforts, Eisenhower asked the Combined Chiefs to send him more combat units, including the two American divisions he understood had not been allocated and any regiments or brigades that could be spared from the United States and the United Kingdom; to consider diverting combat units from other theaters to the European Theater; to equip three existing and two planned French divisions; and finally, “that the maintenance of the fighting efficiency of ground and air forces in this theater be assured by the prompt provision of the necessary ammunition and replacements in personnel and material.”10

On the same day, Eisenhower wrote General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army’s chief of staff, echoing much of what he had told the Combined Chiefs, adding a request that the size of the army be increased to provide a greater number of replacements, and wondering if the Marines might “like to turn over a hundred thousand [men] to us.” In this state of extreme concern about the strength of his combat forces and the urgent need for replacements, Eisenhower observed that he had more than 100,000 black service troops in his theater and concluded, “I feel that in existing circumstances I cannot deny the Negro volunteer a chance to serve in battle.” Addressing the Army’s segregation policies, Eisenhower added, “If volunteers are received in numbers greater than needed by existing Negro combat units I will organize them into separate battalions for temporary attachment to divisions and rotation through front line positions. This will preserve the principle [segregation] for which I understand the War Department stands and will still have a beneficial effect in meeting our infantry needs.”11

Receiving no instructions to the contrary, Eisenhower rewrote a memorandum prepared by General Lee and Brig. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis, the Army’s senior black officer who was serving on the European Theater staff, announcing to Communications Zone troops that black soldiers who wished to volunteer would be accepted for training as infantry riflemen. General Lee promptly instituted the program with the following stipulations:

- Only volunteers with Army General Classification Test scores falling within the top four categories would be accepted

- Only volunteers in the rank of private or private first class would be accepted. However, noncommissioned officers who wished to volunteer could do so by accepting a demotion to private first class.

- No more than 3.5 percent of the enlisted personnel in any individual unit could volunteer.

The Eisenhower-Lee-Davis memorandum offered potential volunteers nothing but the opportunity to fight for their country. In response to Eisenhower’s offer, 4,562 black soldiers volunteered in January and February 1945 for the most hazardous combat assignment in the Army’s ground forces, that of infantry rifleman. Among them were the men destined to serve in CCR Rifle Company, 14th Armored Division. Because of the 3.5 percent limit on personnel from any single unit and the lack of available training facilities, not all of those who volunteered could be accepted. Most of the volunteers came from six military occupational specialties: truck driver, duty soldier, basic, longshoreman, construction foreman, and cargo checker. Many were noncommissioned officers who offered to take the reduction in rank required for their acceptance.13

The Ground Force Reinforcement Command trained approximately 3,200 African American volunteers as infantry riflemen.14 Training was conducted at the 16th Reinforcement Depot at Compiègne, France, 45 miles northeast of Paris. The installation could not accommodate all of the black volunteers at one time, so they were instructed in two successive groups with the smaller, second group waiting until late February to begin training. In order to produce as many replacements as possible in the shortest time, all soldiers, black and white, who were being converted from specialties other than infantry, received only four weeks of training. The black volunteers received training in basic weapons and tactics at the squad and platoon levels. Additional training at the company and battalion levels, as Eisenhower had evidently envisioned, proved impossible as the Ground Force Reinforcement Command was capable of training individual replacements only in units no larger than platoons. Eisenhower advised General Marshall of this problem in early February saying, “Because of lack of time and facilities to train specialists, it appears that I’ll have to use negro volunteers by platoons.” With this decision Eisenhower substantially set aside the Army’s policy of segregation of enlisted men in regimental organizations, as the African American platoons would have to fight with white companies and battalions. Once again, General Marshall did not object.15

The African American soldiers that completed training by 1 March were organized into 37 platoons. The 12th Army Group received 25 of these platoons, which were assigned to various infantry divisions, primarily reporting to the First Army. Each platoon was then assigned to a white company, where it was used as a fourth rifle platoon. The remaining 12 platoons arrived in the 6th Army Group’s area of operations on 10 March and were assigned to the Seventh Army. The army’s commander, Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch, ordered the platoons combined to form four-platoon companies designated as Seventh Army Infantry Companies (Provisional), Nos. 1–3. All three companies were then assigned to the 12th Armored Division, which, having lost an entire armored infantry battalion in January 1945, had a critical need of infantry riflemen. A few weeks later, sixteen more platoons left the 16th Reinforcement Depot. Of these, four platoons went to 6th Army Group’s Seventh Army where they were combined to create Seventh Army Infantry Company (Provisional) No. 4, before being assigned to the 14th Armored Division.16

When this company joined the division at Altenstadt, it had no officers or, for that matter, anyone ranking above private first class. The division, therefore, provided a command staff for the company using white officers and noncommissioned officers drawn from its three armored infantry battalions.17 These units had suffered a considerable number of casualties since November 1944 while fighting primarily in northeastern France, and by late March they were understrength in junior officers and noncommissioned officers. Thus, the levees placed on the battalions for officers and noncommissioned officers were an added burden, which promotions from within and the replacement system, would, at best, be slow to correct.

The division assigned Capt. Derl J. Hess of Headquarters, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion, to command the new company. Captain Hess had commanded his battalion’s Company C from shortly after the formation of the division at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas, in November 1942 until December 1944. He had been serious about his duties and responsibilities as a company commander and had a reputation for being very strict with his men. Although Captain Hess’s company had been in several firefights since arriving at the front, it did not receive its “formal battle christening” until mid-December 1944, when the battalion was ordered to attack a strongly defended portion of the West Wall. During the five-day struggle to breach the German defenses, Captain Hess “broke down under fire” and was relieved of command. He was clearly a poor choice to lead inexperienced troops in combat.18

While some headquarters preferred to assign officers from Southern states to lead black soldiers, the 14th Armored Division gave its CCR Rifle Company a complement of six officers and five noncommissioned officers from geographically diverse origins. Four of the officers were Southerners, but the company commander and the noncommissioned officers were not.19

To further compound the problems of command, CCR Rifle Company received only five noncommissioned officers of the twenty-seven authorized for an armored infantry company by the applicable table of organization and equipment.20 The personnel shortages in the division’s armored infantry battalions prevented the transfer of additional white noncommissioned officers to the new company. The theater eventually agreed to allow the divisions to promote black soldiers to fill these critical vacancies, but this permission did not arrive before victory in Europe had been achieved.21 Without the stability and control provided by some form of noncommissioned officer leadership, the company’s squads could not have functioned properly in combat. Evidently, the natural leaders among the company’s enlisted men, including those who had been noncommissioned officers before volunteering for combat duty, unofficially assumed leadership roles on their own accord, at least while in combat.22

The 240 enlisted men of CCR Rifle Company reported to the division without weapons, equipment, or even enough clothing. Working with the Seventh Army G–4, the division equipped the new company as well as it could at a time when many items, including radios, half-tracks, and trucks, were in short supply. When the black troops arrived, the division had just completed its mission in Operation UNDERTONE, the Seventh Army operation to breach the West Wall and clear the west bank of the Rhine within its zone of operations. The division was in the process of reorganizing and reequipping in preparation for crossing the Rhine and only with difficulty could it locate the necessary equipment and supplies and make them available for issue. As a result, much of the equipment given to the company was in poor condition. Many of the weapons drawn from division stores were battle-worn and required cleaning and repair before they were ready for use in combat. Even some of the clothing issued was worn and in need of mending. The G–4 did manage to issue 500 division patches to the new company, enough to enable each soldier to affix the item to the left shoulder of two sets of combat uniforms. Although CCR Rifle Company was to be used as an armored infantry unit, it received only four used half-tracks, one for each of its platoons. The division met the remainder of the company’s motorized transport requirements by issuing it a sufficient number of 2½-ton trucks.23 Consequently, most of the black “armored” infantrymen would go into combat mounted in open trucks.

Operations of CCR Rifle Company

Under the supervision of their white officers and noncommissioned officers, the soldiers of CCR Rifle Company hurriedly readied themselves and their equipment for action. On 1 April 1945, just four days after joining the division, they accompanied Combat Command R as it crossed the Rhine River near Worms and rushed headlong into the final battles of the war against Germany.24 Regardless of color, the men of the 14th Armored Division would soon discover that although the war was nearly over, there was still plenty of fighting left to be done.

On 3 April CCR Rifle Company was attached to the combat command’s 25th Tank Battalion.25 The two units would fight side by side, except on one or two days, until the end of the war. The company first saw action on the night of 9 April when its 2d Platoon joined elements of the 25th Tank Battalion in an attack on Frickenhausen, a village 25 miles north of Schweinfurt in northern Bavaria. The attack met only light resistance and ended quickly. Two enemy soldiers were killed and seven others were captured.26

Three days later, the 2d and 4th Platoons, led by 1st Lt. George Irwin and 2d Lt. Raymond Gravelle, fought the company’s “first real engagement” at Lichtenfels, a town about 10 miles southeast of Coburg. At 1000 hours on 12 April, Combat Command R reached the Main River across from Lichtenfels and found the bridge into it destroyed. Covered by a smoke screen laid down by the mortar platoon of the 25th Tank Battalion, the black infantrymen forded the river under fire and entered the town. Supported by the tanks of the battalion’s Company C firing across the river, they succeeded in taking the town “after a brisk fight.”27

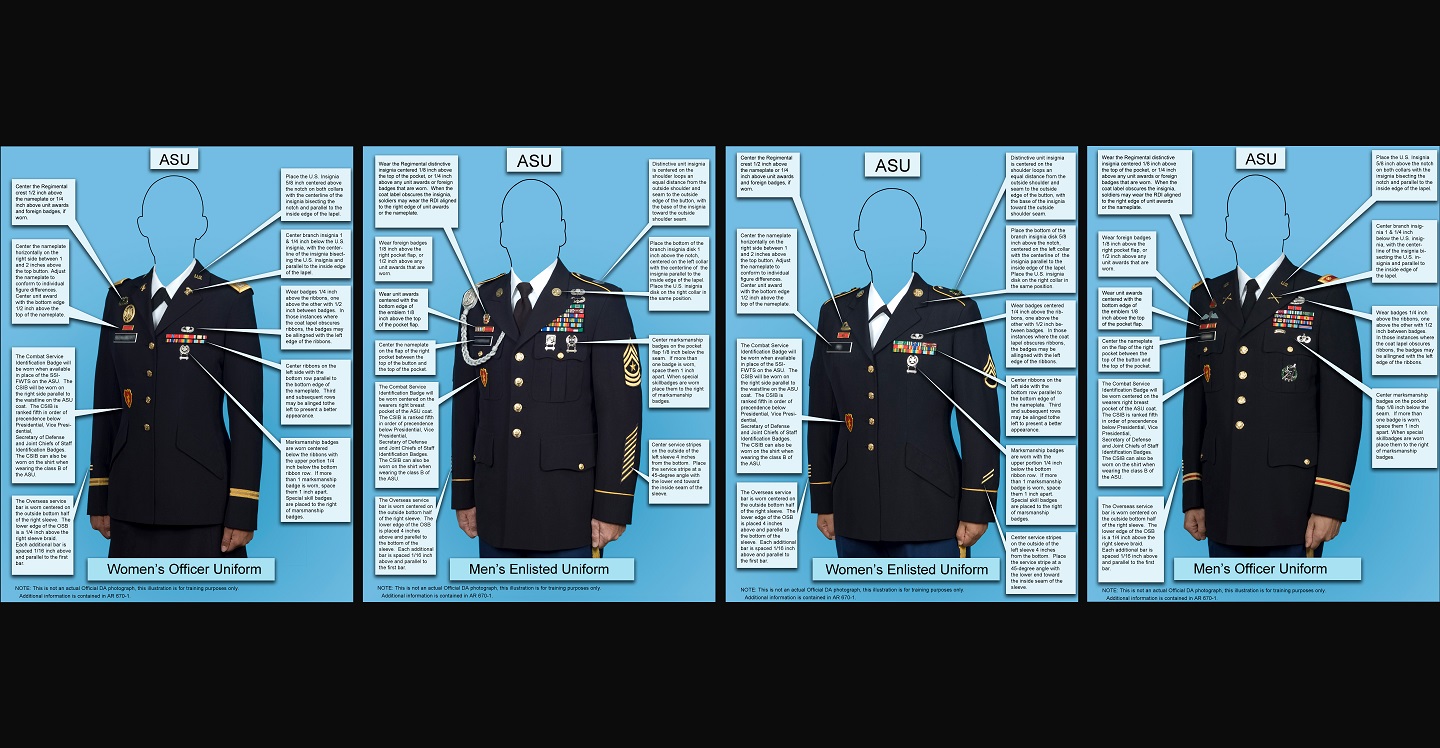

Guarding the long, exposed left flank of the Seventh Army, the 14th Armored Division continued its rapid advance, crossing the Bayreuth-Munich autobahn just south of Bayreuth. Its mission was to cut the autobahn and secure the left flank of the 3d and 45th Infantry Divisions as they moved to attack the relatively well defended city of Nuremberg. Late on 14 April the armored division’s 94th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, less Troops B and C, reached Creussen, seven miles south of Bayreuth. The squadron was several miles in advance of the main body of Combat Command R when it settled into the town for the night. In the early morning hours of the 15th, the squadron found itself in the midst of a sizeable counterattack. The attacking force, Gruppe Grafenwoehr, named for the nearby panzer training center, consisted of two battalions of infantry and 35 tanks. The German force quickly surrounded Creussen and, with it, the 94th Cavalry Squadron.28

On learning of the situation, Combat Command R ordered two platoons of medium tanks from Company B, 25th Tank Battalion, and the 4th Platoon of CCR Rifle Company to reinforce the 94th. About one mile west of Creussen, near the town of Gottsfeld, this small armored-infantry task force came under heavy fire from enemy tanks. Two of the ten medium tanks in the American column were destroyed, and two more were damaged. With their supporting tanks held up by enemy fire, the 4th Platoon went ahead to clear Gottsfeld. The soldiers attacked the town across a broad, open field. They were met by small-arms fire as they advanced. Entering Gottsfeld they were subjected to “considerable enemy artillery” fire but managed to clear the town by mid-afternoon. Three soldiers from the 4th Platoon were wounded in the fighting. Unfortunately, they did not receive prompt medical attention because the company did not have its own medics. Improvising, Sgt. Robert Lavelle confiscated a truck to transport the wounded men back to an aid station. Just before dark, the remaining American tanks arrived on the outskirts of Gottsfeld, where they were again taken under fire by enemy tanks located in a nearby woods. In the ensuing fight, five German Mark IV tanks were destroyed. Having eliminated enemy resistance at Gottsfeld, the small task force moved out at 1700 to join the 94th in the defense of Creussen. Its actions that day, the battalion’s journal reported, “helped considerable [sic] towards relieving the situation in Creussen.”29

The 94th, meanwhile, remained under substantial pressure from the larger enemy force. When the squadron had first entered Creussen, it liberated some 600 forced laborers who had been working in a large munitions factory. Among them were a number of Czechs who were eager to help fight the Germans. The squadron’s commander, Maj. George W. England, who had graduated from West Point the year before the United States entered the war, quickly accepted their services as infantrymen. Equipping his “irregulars” with weapons presented no problem. They were armed with the very rifles and ammunition they had been obliged to manufacture for the Germans. The 94th had also been helped by the timely arrival of a company of the division’s 62d Armored Infantry Battalion shortly before the first German attack. The arrival late on 15 April of the 4th Platoon of CCR Rifle Company and the two platoons of tanks further bolstered the town’s defenses. At times completely surrounded by the enemy, the squadron called in repeated air strikes, which succeeded in knocking out some of the German tanks. When the German attacks pressed uncomfortably close to the American defenses, they were broken up by the massed fires of division artillery. Some German soldiers managed to enter the town, where they took up defensive positions in some of the houses, but they were quickly killed or captured by the Americans and their “irregular” infantry.30 The historian of Combat Command R, Maj. Leland J. Whipple, summarized the actions at Creussen as follows: “Reinforced by CC ‘R’ Rifle Company, the squadron beat back all attacks successfully and destroyed 19 enemy tanks to a loss of two for itself.” Martin Burke, who as a first lieutenant had been a platoon commander with the 94th at Creussen, observed later that CCR Rifle Company was among the most notable of the units that reinforced the squadron at Creussen, all of which “performed admirably and we could not have gotten out of the hole we dug without them.” Official Army historian Charles MacDonald reported, “Within two days, Gruppe Grafenwoehr had ceased to exist.”31

For the next few days, two platoons of tanks from Company C, 25th Tank Battalion, and two platoons of CCR Rifle Company patrolled in and around the towns of Gottsfeld and Creussen. These patrols captured twenty-seven enemy soldiers. In addition, they killed one and wounded two others who chose not to surrender. On 18 April CCR Rifle Company was placed in division reserve along with the rest of Combat Command R. While in reserve, the soldiers of CCR Rifle Company manned roadblocks and outposts in two small towns.32

On the afternoon of 20 April, Combat Command R moved to join the rest of the division south of Nuremberg, where German resistance had ended that day. Their mission was to move south along the autobahn to secure a bridgehead across the Danube River. By late afternoon, the leading elements of the column, which consisted of one platoon of medium tanks from Company C, 25th Tank Battalion, and a platoon of infantry from CCR Rifle Company, had advanced to a point on the autobahn less than a mile south of the village of Altenfelden, when a German force of unknown strength opened fire on it from positions in and around Allersberg, a mile and a half to the east of the highway. CCR Rifle Company was ordered to advance and clear Allersberg. Before it had gone very far, the company’s 4th Platoon was hit by heavy small arms and artillery fire. One soldier was killed, and five were wounded in the fusillade. The intense enemy fire compelled both the battalion and the black infantrymen to pull back about 1,000 yards. Combat Command R then assumed defensive positions for the night in Altenfelden, while its 501st Armored Field Artillery Battalion fired on Allersberg and nearby enemy positions from time to time during the night. This action initiated a three-day battle.33

After the fall of Nuremberg, several German divisions, including the 17th SS Panzergrenadier, had concentrated near Allersberg, fifteen miles southsoutheast of Nuremberg.34 Although badly depleted in men and material, these exhausted German organizations proved that they could still fight. Before the battle ended, two of the 14th Armored Division’s three combat commands had joined the engagement. CCR Rifle Company played a prominent role throughout the fighting.

Just after sunrise on 21 April, three enemy tanks moved onto the high ground southeast of Allersberg and opened fire on targets in Altenfelden. Gunfire from the American tanks and tank destroyers there neutralized two of the enemy tanks. The combat command then attempted to resume its march south on the autobahn. At the front of the column were a platoon of tanks from Company C, 25th Tank Battalion, and the black infantrymen of 1st Platoon, CCR Rifle Company. Shortly after 0900 hours, as the column reached a road junction on the autobahn just west of Allersberg, it came under heavy fire from German artillery and tanks. CCR Rifle Company lost two vehicles and suffered several casualties.35

As the two lead platoons began clearing the road junction, the remaining three platoons of CCR Rifle Company pushed on to the nearby town of Polsdorf. The German gunners opened fire on the infantrymen as they raced through the deadly intersection mounted in their open, 2½-ton trucks. Fortunately, none of these vulnerable vehicles was hit, and there were no casualties. Others in the column were not so fortunate. A medium tank and a tank destroyer were knocked out by antitank fire as they attempted to cross the intersection. So great was the volume of the antitank fire that swept the intersection that the tankers of Company C nicknamed it “88 Junction,” after the 88-mm. antitank rounds fired at it by a German Mark VI Tiger tank.36

Inside the stricken American medium tank, the crew scrambled to exit their vehicle. Opening the hatches, they were met with a hail of accurate machine-gun and small-arms fire that effectively prevented their escape. Trapped inside their tank, the men waited in fear of being hit by another antitank round. Seeing that the tank crew was trapped, soldiers from the 1st Platoon of CCR Rifle Company braved the heavy enemy fire and made their way to the immobilized tank. Talking with the vehicle’s commander via the tank’s external communications system, the infantrymen learned the general location of the enemy machine gun. They went after it. In a brief firefight, they succeeded in knocking out the machine gun, killing and capturing several enemy soldiers in the process. No longer pinned inside by the German machine gun, the crew exited their tank and made their way back to Altenfelden.37 Once there, the tankers found their safety to be tenuous, at best.

At 0915, while the road junction remained under attack, division soldiers still in Altenfelden spotted approximately 100 enemy troops moving toward the town. Supported by artillery fire, small groups of SS soldiers soon began to make their way into Altenfelden, where they sewed confusion and inflicted a few casualties. Combat Command R responded with an urgent radio call for reinforcements. As most of the 25th Tank Battalion had not yet reached “88 Junction,” the bulk of the unit was able to return to Altenfelden without additional losses, but of the four platoons of CCR Rifle Company, only the 3d managed to rejoin the battalion there. Two companies of the 62d Armored Infantry Battalion joined these black infantrymen in the support of the 25th Tank Battalion in Altenfelden.38

Despite being subjected to accurate shelling by German artillery, the elements of Combat Command Reserve in Altenfelden managed to defeat the attacking Germans by 1500 hours. An attack the Americans launched toward Allersberg an hour later, however, proved unsuccessful. The combat command lost two tanks, a tank destroyer, and an assault gun in the defense of the town on 21 April.39

As the fighting subsided in Altenfelden, a platoon of Company C, 25th Tank Battalion, accompanied by the 2d and 4th Platoons of CCR Rifle Company, advanced down the autobahn to Göggelsbuch, two miles south of Altenfelden. Later that evening, the 1st Platoon of CCR Rifle Company joined the American forces in Göggelsbuch. Combat Command R issued orders for the units in Göggelsbuch to attack Allersberg the following morning, 22 April. During the night, American XV Corps and 14th Armored Division artillery bombarded the German forces in Allersberg in preparation for the impending attack.40

The attacking force consisted of six platoons of infantry, three from CCR Rifle Company and three from Company A, 62d Armored Infantry Battalion, which had arrived the previous day in response to the combat command’s call for reinforcements. The infantrymen were supported by eight medium tanks manned by Company C, 25th Tank Battalion, two assault guns, and one tank destroyer. CCR Rifle Company led the attack. Moving from Göggelsbuch through a wooded area toward Allersberg, the black infantrymen were confronted at close range by two Tiger tanks that had been concealed among the buildings at the edge of town. The black soldiers held their ground, firing on the advancing tanks with their rifles and submachine guns, while their bazooka teams took up positions and opened fire. Several bazooka rounds found their targets but did not penetrate the thick armor of the German tanks. As the enemy tanks closed to within 15 yards of the infantry positions, Pfc. Percy Smith of the 1st Platoon fired his bazooka and succeeded in disabling one of the Tigers. Private Smith was killed by return fire from the same tank, and other soldiers were wounded. Both infantry companies were then ordered to withdraw and return to Göggelsbuch. As before, without medics of their own, CCR Rifle Company’s wounded men had to wait for medical treatment until 1st Lt. George Whiten could arrange for their evacuation to the rear.41

The infantry units that attacked Allersberg in the morning launched another attack on the town at 1630 hours. This time the attack was supported by the tanks of Company B, 25th Tank Battalion, firing from positions near Altenfelden. CCR Rifle Company again led the attack, with the three platoons of Company A, 62d Armored Infantry Battalion, in direct support. The infantrymen were met with heavy fire from tanks, machine guns, and small arms, and this time they made little headway. The attackers withdrew as darkness approached, and CCR Rifle Company arrived in Altenfelden at 2000 hours.42

Because of the continued enemy resistance at Allersberg, division headquarters assigned the direction of the attack to Combat Command A and ordered Combat Command R to move on to the southeast. The 25th Tank Battalion and CCR Rifle Company were attached to Combat Command A. During the night, enemy troops cut the autobahn yet again, this time north of Altenfelden. The following morning, two platoons of CCR Rifle Company led another attack on Allersberg. They soon discovered that the bulk of the German defenders had withdrawn during the night, and the black infantrymen captured the town, overcoming what the operations journal of the 25th Tank Battalion described as “light, fanatical resistance.”43

At a time when organized German opposition was collapsing all across the front, the three-day battle at Allersberg had been particularly fierce. The fighting there impressed even the veterans of the 62d Armored Infantry Battalion, whose unit history reported that the battalion’s “A Company made the attack with CCR Rifle Company (Colored). They will long remember the fighting there and the Krauts [sic] ‘Tiger’ tanks.” Maj. Leland Whipple, the S–2 (intelligence officer) of Combat Command R, who also served as its historian, characterized the fighting at Allersberg as “one of the most intense and savage of all battles participated in by CC ‘R.’ ” CCR Rifle Company led each of the attacks on Allersberg, but the unit was not to blame for the repeated failures in capturing the strongly defended town. As Maj. William E. Shedd III, the S–3 of the 25th Tank Battalion, observed in his battalion’s operations journal on 22 April, “More Inf[antry was] needed to make [a] successful attack.” A 1942 Military Academy graduate who would serve as an Army major general from 1970 to 1977, Shedd was a competent analyst.44

On 15 April General Eisenhower issued orders that moved further west the zones of advance of the Seventh and Third Armies as they began offensive operations aiming deep into southern Germany. This reorientation left the 14th Armored Division within the zone of advance newly assigned to the Third Army. General Patch and Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr., the Third Army’s commander, met the following day and agreed to transfer the 14th to Patton’s army. The division was transferred to the Third Army on 23 April and remained attached to it until after victory was achieved in Europe.45

On 24 April CCR Rifle Company advanced south a dozen miles through Untermässing to Schutzendorf. Learning that a group of enemy soldiers were in the woods nearby, the company’s officers ordered patrols from each platoon to sweep the woods. Within an hour, they returned, having captured eight enemy soldiers and killed several more. Afterwards, another patrol, made up of men who volunteered for the duty, reentered the woods and captured four more prisoners. CCR Rifle Company and the 25th Tank Battalion returned to the control of Combat Command R on 27 April, crossed the Danube River at Ingolstadt, and moved to Furth, 35 miles northeast of Munich. Over the next two days, rifle company patrols in this area captured 42 prisoners.46

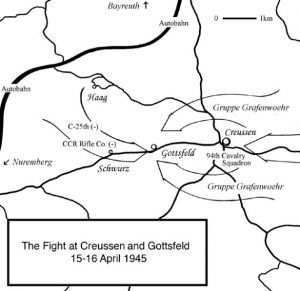

On the afternoon of 29 April, Combat Command R advanced another five miles to the small town of Altdorf, leaving it just three miles northwest of the Isar River city of Landshut. Its mission was to clear the portion of the city on the north side of the river and establish a bridgehead to the south. That evening a rifle platoon of Company A, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion, made a probing attack into the outskirts of Landshut. The platoon soon ran into strong resistance and was forced to fall back to Altdorf. Remnants of the 36th and 256th Volksgrenadier Divisions and the recently formed 38th SS Panzergrenadier “Nibelungen” Division were in Landshut, prepared to put up a strong defense as they bought time to complete their withdrawal across the river.47

The following morning several elements of Combat Command R moved from Altdorf to attack the enemy in Landshut. CCR Rifle Company and the medium tanks of Company A, 25th Tank Battalion, were attached to the 68th Armored Infantry Battalion for this effort. The initial attack, made by Companies A and C, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion, was successful in capturing the area north of the city’s rail center. The rail center had been so badly damaged by heavy Allied bombing that much of it was a veritable no man’s land, carpeted with bomb craters and littered with twisted, broken railcars and steam engines. Beyond, between the rail center and the river, were the bombed-out buildings and rubble-filled streets of Landshut. The fact that none of the bridges over the canals in the area remained intact added to the overall difficulties of the terrain. As a result, the second phase of the attack had to be made without tank support.48

At 1100 hours Company B, 62d Armored Infantry Battalion, on the left and CCR Rifle Company on the right attacked into the rail center from positions on the right flank of the 68th Armored Infantry Battalion and then pushed on into the devastated city. The two companies soon came under intense fire from artillery and antitank guns located across the river. The unit history of the 62d records that “with some of the bitterest fighting of the war, the town was taken house by house[,] the enemy utilizing to its fullest extent his artillery, mortar, and direct fire with SP’s [self-propelled artillery pieces] and AT [antitank] guns. Withering MG [machine gun] and rifle fire was encountered. At 1400 all of Landshut north of the Isar River was clear.” In three hours of hard fighting, CCR Rifle Company suffered twenty-one casualties.49

As the war in Europe entered its final days, CCR Rifle Company again operated with the 25th Tank Battalion. The two units continued south, crossed the Isar River at Moosburg on 1 May, and pushed rapidly toward the Inn River. On 2 May, supported by the tanks of Company A of the tank battalion, two platoons of CCR Rifle Company cleared the towns of Hilpolding and Dorfen, 13 and 18 miles south of Landshut, respectively. Finding no enemy opposition, they moved to the southeast and crossed the Inn River. The advance ended late that afternoon at the town of Stephanskirchen, where the black soldiers took 110 prisoners of war. The division was then ordered to halt and secure the area. The next day, elements of CCR Rifle Company, supported by a few light tanks, cleared the surrounding towns. A week after it arrived in Stephanskirchen, the war in Europe was over. In 38 days of campaigning, CCR Rifle Company had lost 6 men killed, 37 wounded, and 1 man missing in action.50

CCR Rifle Company and the 25th Tank Battalion remained in Stephanskirchen until 11 May. The two units were then ordered north to Ingolstadt on the Danube to take over security duties for a week from the 8th Tank Destroyer Battalion. The tank battalion and CCR Rifle Company returned to the Inn River valley on 18 May, taking over occupation duty at Töging am Inn, just east of Mühldorf, from elements of the 13th Armored Division. Two days later, the division detached CCR Rifle Company from the 25th Tank Battalion and returned it to the direct control of Combat Command R.51

The black rifle company’s service with the 14th Armored Division did not end without incident. A few days after the company returned to the control of Combat Command R, some of its men were drinking alcohol and making noise in their quarters, when Maj. John P. Campana, the division’s Assistant G–1, came in and tried to quiet them down. As Campana chewed out some of the black soldiers, someone fired an errant shot at him. In response, Col. James P. Hill, the division’s chief of staff, a Regular Army officer who came from South Carolina, ordered that the company be taken to the field and drilled eight hours a day.52

To carry out these orders, the division chose Capt. Jack R. DeWitt, a 1942 University of Wisconsin Law School graduate who was the commander of Company C, 19th Armored Infantry Battalion. Summoned to division headquarters, Captain DeWitt learned of his additional responsibilities from the division G–1, or personnel officer, Lt. Col. Albert Stephens. DeWitt later re-counted the conversation as follows: He said, “Jack, you’ve been tough as hell with those krauts and we need someone who is going to be tough. We have this nigger company that has been raising hell here and we want you to take them out in the field and drill them eight hours a day. They took some shots at a white officer from Division Headquarters. The officer they had [Captain Hess] is afraid of them, and we knew you originally came from the south [Oklahoma] and that you can handle these niggers.”

I said, “Sir, did all of these men screw up?” He said, “No, but Colonel Hill wants you to take the whole bunch and drill them eight hours a day.”53

After his meeting with Colonel Stephens, Captain DeWitt decided to learn more about the soldiers of CCR Rifle Company. He asked his friend 1st Lt. John P. Meyer about them. Lieutenant Meyer was an officer in the 501st Armored Field Artillery Battalion who had been assigned as forward artillery observer for CCR Rifle Company for much of its time in combat. He had thus had ample opportunity to observe the conduct of the black infantrymen under fire. DeWitt learned from Meyer that the soldiers in CCR Rifle Company had fought Tiger tanks with rifles and submachine guns and that they had gone into combat, even under fire, mounted in open trucks. Captain DeWitt also found out that these men were all volunteers and that some of them had accepted demotions in rank in order to be allowed to fight for their country as infantrymen. Hearing these things, he realized that the men of CCR Rifle Company had demonstrated “a good deal of bravery” and concluded that they had earned the right to fair and equitable treatment. He reported, “Since I thought that this was an injustice, I made up my mind to treat these men as fairly as I possibly could. When they reported to our area, I arranged for them to have the same kind of quarters that C Company had, namely the platform tents, and I told the men that I did not care whether they were black, white or striped. If they did a good job of soldiering, we would get along in fine shape and they would be treated fairly, and if anyone got out of line, I would find a way to take care of them the same way I would with the white soldiers.”54

Captain DeWitt’s white company was guarding a prisoner of war camp that held a number of high-ranking German Army officers and SS troops. He sought to use the black soldiers to help guard these prisoners, but his request was denied by division headquarters. True to his word, DeWitt treated the black soldiers fairly. Those who failed to adhere to the requirements of good order and discipline were punished in the same manner as were white soldiers. While the company was under his command, it experienced no more shooting incidents or other major breaches of discipline. In his final evaluation of the black soldiers, Captain DeWitt observed, “Nearly all of them were good soldiers. After all, they were volunteers and had enough courage to go into the infantry when they could have had a safe spot in the quartermaster [Quartermaster Corps] or some port battalion. We had about the same percentage of them get into trouble as got into trouble in the white company.”55

Disbandment

With the war over in Europe, the emergency that had led to the assignment of black volunteers to previously all-white divisions was at an end, and General Eisenhower moved promptly to reestablish the three-decade-old tradition of racial segregation in the Army’s divisions. Consequently, on 4 June CCR Rifle Company was disbanded, and its men were transferred to the 395th Quartermaster Truck Company, which was attached to the 14th Armored Division.56

In late June the 14th Armored Division’s headquarters expressed some dissatisfaction with the performance of CCR Rifle Company to Maj. Gen. Louis A. Craig, the new commander of XX Corps, to which the division was then assigned. The specifics of this assessment are not known, but they appear to be at odds with the observations of eyewitnesses and the historical record of CCR Rifle Company’s performance in combat.57

For its part, the Seventh Army, under which the 14th Armored Division had served until 23 April, criticized the provisional rifle companies, pointing particularly, as historian Ulysses Lee summarized its objection, to “poor control and discipline within the companies, especially after taking towns.” General Patch, the army commander, informed General Davis of the European Theater staff that the platoons had not been able to function effectively as companies and did not perform very well as armored infantry. Davis responded that the black infantry platoons had not been trained to fight as companies, since the original plan was to employ them as individual platoons attached to white companies. General Jacob L. Devers, the 6th Army Group commander, told General Patch that “a better solution would have been to use them as rifle platoons in an Infantry Division.” It is not known what opinions General Patton or his headquarters staff had regarding the performance of CCR Rifle Company, 14th Armored Division, or the black rifle platoons in other divisions briefly attached to Third Army in April and May 1945.58

The lack of discipline displayed by soldiers of CCR Rifle Company in the “shooting incident” is obvious. At least some of the black soldiers in the unit engaged in serious misconduct when confronted by a critical officer. Where the company’s officers and noncommissioned officers were at the time of the incident is not known. If they had become inattentive, it may be fair to lay part of the blame for the breakdown of discipline in the company on inadequate leadership. Captain DeWitt’s positive experience with the same black soldiers soon afterwards indicates that the conduct of the black soldiers improved to acceptable levels when they were exposed to good leadership and proper discipline.

Before going into combat, the soldiers of CCR Rifle Company received only minimal training as infantry riflemen and no training whatsoever as a full company. Their company commander was an infantry officer who had previously broken under fire and, as a result, been relieved of command. They were sent into action with less than one-fifth of the complement of noncommissioned officers authorized for an armored infantry company. To further complicate their situation, the four platoons were often used together as an infantry company, expected to function as a single unit within a complex combined arms organization. Despite these sizeable handicaps, the black soldiers, in the words of General Shedd, the wartime S–3 of the 25th Tank Battalion, “attacked when ordered to do so, they continued to advance even when they were under heavy enemy fire, they never broke in combat or withdrew from an engagement without orders, and they maintained proper discipline on the battlefield. They were no different than the white soldiers of the division.” The division’s soldiers, at least those who had seen the black infantry riflemen in action, seem to have shared this appraisal. The esteem in which these veterans of the division held the soldiers of CCR Rifle Company was evidenced by the 1966 election of wartime Pfc. Dennis C. White, a veteran of the company, as the second president of the 14th Armored Division Association. Thanks, at least in part, to African American volunteers like those of CCR Rifle Company, the nation as a whole had by then come to accept the view that American soldiers, black and white, could best serve their country in an Army undivided by racial segregation.59

Notes

The author wishes to thank the many veterans of the 14th Armored Division who patiently answered his questions and, in some cases, made available to him documents and photographs that contributed substantially to the preparation of this article. He was, unfortunately, unable to locate any veterans of CCR Rifle Company whose health would allow them to be interviewed.

1. Robert L. Bullard, Personalities and Reminiscences of the War (Garden City, N.Y., 1925), p. 298. Bullard commanded the U.S. Second Army in France during World War I.

2. Msg, Eisenhower to General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, 7 Jan 1945, printed in Alfred D. Chandler Jr. and Louis Galambos, eds., The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, 21 vols. (Baltimore, 1970–2001), 4: 2409.

3. 47th Tank Battalion History from New York on Hudson to Muhldorf on Inn (Mühldorf am Inn, 1945), pp. 31–32; Walter R. Dickson, Combat History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion: October 12th, 1944 to May 9th, 1945 (Munich, 1945), pp. 62–63, 97, map after p. 12; Typescript, “Historical Record, Headquarters, VI Corps,” March 1945, pp. 40–41, at U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, Pa.; Charles B. MacDonald, The Last Offensive, United States Army in World War II (Washington, D.C., 1973), pp. 263–64. Altenstadt is located a mile east of the larger town of Wissembourg.

4. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, pp. 97–100, summarizes the wartime actions of CCR Rifle Company. Ulysses Lee, The Employment of Negro Troops, United States Army in World War II (Washington, D.C., 1966), pp. 688–703, provides an overview of the formation and employment of the black infantry platoons and companies that served in white infantry and armored divisions in Europe in 1945.

5. Roland G. Ruppenthal, Logistical Support of the Armies, United States Army in World War II, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1953–59), 2: 304, 307–08, 317–21, 326–29.

6. Ibid., pp. 321, 324.

7. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, pp. 5–20, 128–35, 688–89; Bullard, Personalities and Reminiscences of the War, p. 298 (quote).

8. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, pp. 75–76, 123–26, 488–590; Morris J. MacGregor Jr., Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965, Defense Studies Series (Washington, D.C., 1965), pp. 30–33; Mary Lee Stubbs and Stanley Russell Connor, Army-Cavalry, Part 1: Regular Army and Army Reserve, Army Lineage Series (Washington, D.C., 1969), pp. 70–71.

9. Jeffrey J. Clarke and Robert Ross Smith, Riviera to the Rhine, United States Army in World War II (Washington, D.C., 1993), pp. 492–532.

10. Msg, Eisenhower to Combined Chiefs of Staff, 7 Jan 1945, in Chandler and Galambos, Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, 4: 2407–08.

11. Msg, Eisenhower to Marshall, 7 Jan 1945, in ibid., pp. 2408–09, quotes, p. 2409. The European Theater was already attaching field artillery, tank, and tank destroyer battalions with black enlisted personnel to its divisions. See Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, pp. 644–46, 654–55, 661, 667, 670, 675, 680.

12. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, pp. 689–94; Marvin E. Fletcher, America’s First Black General: Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., 1880–1970 (Lawrence, Kans., 1989), pp. 138–39.

13. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, p. 693.

14. None of the official histories gives a definitive total of the number of volunteer black riflemen trained in Europe. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, states (p. 695) that 2,253 soldiers had finished training by 1 March and were formed into 37 platoons. These platoons had an average strength of just over 60 men each, which accorded with Eisenhower’s wish that they be formed overstrength so they could absorb combat losses without the need for additional replacements. Lee adds (ibid.) that another 16 platoons completed training later in March but does not state the number of men who formed them. Again assuming an average strength of 60 men per platoon, the author calculates the strength of these platoons at 960 men, bringing the total number of men trained to just over 3,200. CCR Rifle Company, 14th Armored Division, was comprised of 4 of these latter 16 platoons, and it had 60 men in each of its platoons. The figures of 2,250, 2,500, and 2,800 given, respectively, by Ruppethal, Logistical Support of the Armies, 2: 322; MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, p. 52; and Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, p. 693, apparently represent substantial portions but not all of those trained.

15. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, pp. 693–95; Ruppenthal, Logistical Support of the Armies, 2: 328–29; Msg, Eisenhower to Marshall, 9 Feb 1945, printed in Chandler and Galambos, Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, 4: 2474 (quote); MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, p. 46.

16. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, pp. 695, 699.

17. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 97.

18. Typescript, “Unit History: 68th Armored Infantry Battalion from Port of Embarkation to V-E Day,” p. 10, first quote, copy in author’s possession; Interv, author with Lester D. Lamb, wartime captain and commander of the Service Company, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion, 29 Jul and 8 Aug 2004, second quote; Typescript, Jack R. DeWitt, “Soldier Memories,” p. 132, copy in author’s possession. None of the veterans interviewed about CCR Rifle Company for this article remembered seeing Captain Hess with his unit in combat, nor has the author found any reference in printed sources or documents relating to Hess’s actions with CCR Rifle Company between the day he assumed command and V-E Day.

19. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 97; Joseph Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division (Atlanta, 1945), Division Roster.

20. Table of Organization and Equipment No. 7–27, War Department, 15 Sep 1943, pp. 2–3, copy in Force Structure and Unit History Branch, Center of Military History.

21. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, p. 696.

22. Interv, author with Jack R. De-Witt, who as a captain commanded Company C, 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, during the war and CCR Rifle Company after V-E Day, 9 Aug 2004.

23. G–4 Journal, 14th Armored Division, 26–31 Mar 1945, in box 16311, World War II Operational Reports, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Record Group 407, National Archives, College Park, Md. (hereafter RG 407, NA); Interv, author with retired Maj Gen William E. Shedd III, wartime S–3 (Operations Officer) of the 14th Armored Division’s 25th Tank Battalion, 7 and 15 Jan 2001; Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, pp. 97–98. According to the G–4 Journal, CCR Rifle Company was provided with the following vehicles: four half-tracks, two peeps (jeeps), and seven 2½-ton trucks. The half-tracks were drawn from the division’s armored infantry battalions.

24. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 97.

25. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 3 Apr 1945, in file 614-TK-(25)-3.2, box 16345, RG 407, NA.

26. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 97; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 9 Apr 1945.

27. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, pp. 97–98, quotes; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 12 Apr 1945; Edward F. Kelly, Steady-On! Combat History of Co C[,] 25th Tank Bn. (Munich, 1945), p. 23.

28. MacDonald, The Last Offensive, p. 423; Rpt, Maj Leland J. Whipple, “CC ‘R’ History, April 1945,” p. 3, file 614-CCR-0.3, World War II Operation Reports, box 16335, RG 407.

29. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 98; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 15 Apr 1945, quotes.

30. Interv, author with retired Col George W. England Jr., wartime commander of the 94th Cavalry Squadron, 5 May 2005; Interv, author with retired Col Carl P. Keiser Jr., wartime S–3 of the 94th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, 30 Jun 2006; Typescript, “History of Troop A, 94th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, Mechanized, 14th Armored Division,” pp. 7–8, copy in author’s possession; Martin J. Burke, Memoirs of a “Liberator”: Anecdotes of the 14th Armored Division (Huntsville, Ala., 1968), pp. 22–23, copy in author’s possession.

31. Rpt, Whipple, “CC ‘R’ History, April 1945,” p. 3 (first quote); Burke, Memoirs of a “Liberator,” p. 23 (second quote); MacDonald, The Last Offensive, p. 424 (third quote).

32. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 16–20 Apr 1945. Burke retired as an Army colonel in 1974.

33. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 98; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 20 Apr 1945.

34. HQ Twelfth Army Group situation map, 22 Apr 1945, posted at http:// memory.loc.gov/ammem/milmapquery. html, search for April 22.

35. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 20–21 Apr 1945; Kelly, Steady-On, p. 25; Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 98.

36. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 98; Kelly, Steady-On, p. 25.

37. Interv, author with wartime Pfc. Meyer Levin, the “loader” in the medium tank knocked out at the road junction, 5 Jan and 11 Aug 2001.

38. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 21 Apr 1945; Rpt, Whipple, “CC ‘R’ History, April 1945,” p. 4; Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 98; Rpt, 62d Armored Infantry Battalion, Unit Historical Report, Apr 1945, p. 2, in file 614-Inf-(62)-0.2, box 16342, World War II Operational Reports, RG 407, NA.

39. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 21 Apr 1945; Rpt, Whipple, “CC ‘R’ History, April 1945,” p. 4.

40. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 20–21 Apr 1945; Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 99; Typescript, “A History of Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 14th Armored Division Artillery, Oct. 14, 1944–May 8, 1945,” p. 58, copy in author’s possession. The last account states that division fires on Allersberg were reinforced by the following field artillery battalions from the XV Corps Artillery: 250th (105-mm. howitzer), 961st (155-mm. howitzer), and 989th (155-mm. gun).

41. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 99; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 22 Apr 1945; Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division, Division Roster, Casualty Roster.

42. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 22 Apr 1945.

43. Ibid., 22–23 Apr 1945.

44. 62 Armored Infantry Battalion History (n.p., n.d.), p. 106, first quote; Rpt, Whipple, “CC ‘R’ History, April 1945,” p. 3, second quote; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 22 Apr 1945, third quote; Typescript, “Resume of Service Career of William Edgar Shedd III as of 30 November 1977,” in biographical file, William E. Shedd III, Historical Records Branch, CMH.

45. MacDonald, The Last Offensive, pp. 421–22; Seventh U.S. Army Report of Operations in France and Germany, 1944–1945, 3 vols. (Munich, 1945), 3: 1017.

46. Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 99; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 27–28 Apr 1945.

47. Unit History, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion from Port of Embarkation to V-E Day (n.p., n.d.), p. 31; HQ Twelfth Army Group situation map, 30 Apr 1945, posted at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/ milmapquery.html, search for April 30; Military Intelligence Division, War Department, Order of Battle of the German Army, 1 March 1945 (Washington, D.C., 1945), pp. 151–52, 216–17; Marc J. Rikmenspoel, Waffen-SS Encyclopedia (Bedford, Pa., 2004), pp. 56–57.

48. History, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 31; Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division, ch. 14; photos of Landshut rail yards taken by William Z. Breer in Jun 1945, in author’s possession.

49. History, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 31; 62 Armored Infantry Battalion History, p. 105 (quote); Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 99; Carter, History of the 14th Armored Division, ch. 14.

50. Franklin Wallace, ed., History, 125th Armored Engineer Battalion: Camp Shanks, New York to V-E Day Inclusive (Diessen, Germany, 1945), p. 85; S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 1–3 May 1945; Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 100; Interv, author with Charles J. Brix, a veteran of the Service Company, 25th Tank Battalion, 20 Jul 2006. There are three towns named Stephanskirchen in southern Bavaria, each located east of the Inn River and each within twenty miles of the others. The Stephanskirchen five miles east of Wasserburg am Inn appears the most likely stopping point of CCR Rifle Company.

51. S–3 Journal, 25th Tank Battalion, 1–20 May 1945.

52. Typescript, DeWitt, “Soldier Memories,” p. 132.

53. Ibid., p. 131. DeWitt was one of the most highly decorated soldiers in the 14th Armored Division, having received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, and the British Military Cross. After the war he taught at the University of Wisconsin Law School, served as president of the State Bar of Wisconsin, and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Army Reserve. See Wisconsin Law Foundation, The Letter of the Law 4 (Winter 2005): 4.

54. Typescript, DeWitt, “Soldier Memories,” pp. 131–32, quote, p. 132; Interv, author with John P. Meyer, wartime forward observer in Battery B, 501st Armored Field Artillery Battalion, 14 Aug 2001.

55. DeWitt, “Soldier Memories,” pp. 132–33.

56. MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, p. 53; Dickson, History of 19th Armored Infantry Battalion, p. 100.

57. Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, p. 700, citing a Ltr, Hq, 14th Arm Div, to CG, XX Corps, 20 Jun 45. The author has not been able to locate this letter.

58. Ibid., pp. 700–01, quotations, p. 701. Patton was in the United States when XX Corps forwarded the 14th Armored Division’s letter of dissatisfaction to him. See Martin Blumenson, The Patton Papers, 2 vols. (Boston, 1972–74), 2: 720–22, 727. The 1st and 99th Infantry Divisions were among those that received infantry platoons with African American personnel. The 99th Infantry Division was assigned to the Third Army on 19 Apr 1945; the 1st Infantry Division was assigned to the Third Army on 6 May 1945.

59. Interv, author with Shedd, 7 and 15 Jan 2001, quote; Interv, author with Meyer, 14 Aug 2001.