A member of the U.S. Army Band plays “Taps” at the 151st Memorial Day observance at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia in 2019. Arlington National Cemetery

On May 31, 1864, Union and Confederate armies exchanged the first shots in the bloody two-week Battle of Cold Harbor that saw over 17,000 combatants killed, wounded, or captured. “I saw no live man lying on this ground. The wounded must have suffered horribly before death relieved them, lying there exposed to the blazing southern sun o’ days, and being eaten alive by beetles o’ nights,” wrote one Union Soldier after the battle concluded on June 12. Cold Harbor was one of a score of bloody battles that tore the United States apart during the Civil War.

Over 150 years later, Americans bow their heads in silence to remember fallen Soldiers in a national day of mourning. Originally known as Decoration Day, this day of remembrance became Memorial Day in 1971 and is observed annually on the last Monday of May. While many Americans celebrate the day with barbeques and picnics, the original intent of the holiday, to honor fallen Soldiers, has a long history. Memorial Day’s origins are shrouded in uncertainty, and historians are still trying to uncover its full story.

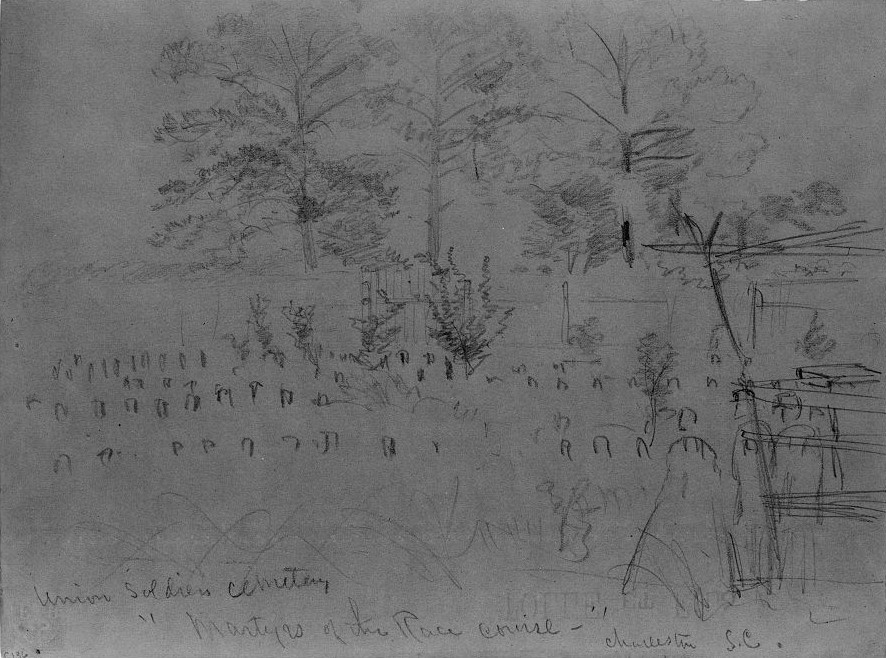

Local communities placed flowers and decorated Soldiers’ graves as early as 1864, even before the Civil War concluded in 1865. The women of Boalburg, Pennsylvania, led contingents of civilians to the cemeteries at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1864, although these ceremonies were small, one-time events. The first evidence of public grave decoration ceremonies in the United States comes from Charleston, South Carolina in 1865. During the Civil War, the Confederate army used one of the city’s racecourses as a prison for captured Soldiers. Many of those who died in captivity were buried in unmarked graves outside the racetrack pavilion. Charleston’s African American population decided to rebury the dead Soldiers with honors, spending ten days digging new graves and building a fence, complete with an archway reading “Martyrs of the Race Course.” On May 1, 1865, 10,000 residents, mostly African American, led a procession to the new cemetery, singing patriotic songs, decorating the graves with flowers, and holding prayers. Three white and Black Army regiments ended the day with a practice drill and a march around the graves. Charleston’s celebration was eventually eclipsed by other ceremonies and was mostly forgotten, largely because its main participants were Black.

Pencil drawing of the Union Soldiers cemetery, “Martyrs of the Race Course,” in Charleston, South Carolina by Alfred Waud. Library of Congress

The Civil War ended in 1865; several hundred thousand troops died in the conflict. With so many deaths, nearly every family in America felt the grief of losing a loved one. The need for a space to grieve and collectively remember the devastation of the war gained national significance. The creation of the National Cemetery System in 1865 and the reburial of Soldiers’ remains kept the fallen at the forefront of the post-war mind.

The following year in 1866, several other towns across the country held their own ceremonies and now claim to be the birthplace of Memorial Day. The New York Tribune recorded one event in Columbus, Mississippi, where women placed flowers on both Union and Confederate Soldiers’ gravestones from the Battle of Shiloh. Inspired by the news of honoring the fallen Soldiers from both sides, American poet Francis Miles Finch wrote one of his best-known poems, “The Blue and the Gray,” the following year. At nearly the same time in Carbondale, Illinois, over 200 Union veterans and civilians cleaned headstones at Woodlawn Cemetery. They organized a community-wide ceremony with Maj. Gen. John A. Logan of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union veteran’s organization, delivering the leading speech. In May 1866, the town of Waterloo, New York, held its own celebrations attended by nearly the whole community and included businesses closing in observance of the ceremony.

The first official declaration for a day of remembrance came from General Logan in 1868. He had received a letter from an unnamed Soldier earlier in the year suggesting an annual holiday to honor fallen Civil War Soldiers. On May 5, 1868, Logan spoke before a crowd at a commemoration honoring local veterans and issued General Orders, No. 11. He declared May 30 as a day dedicated to “cherishing tenderly the memory of our heroic dead” and “gather[ing] around their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with choicest flowers of springtime.” The call reached every part of the country and the day became known as “Decoration Day.” President Andrew Johnson supported the movement by granting federal workers leave to attend the ceremonies.

Girls and boys pose with flowers they collected for Decoration Day on May 28, 1899. Library of Congress

Following Logan’s orders, Decoration Day was observed as close to the original May 30 date as possible, though each community celebrated with their own variations. States proclaimed Decoration Day a holiday at different times. New York was the first in 1873, and most northern states followed suit by 1890. Many southern states refused to declare it an official holiday until after World War I. Instead, states such as Mississippi and Alabama honored the Confederate dead in separate ceremonies and each state observed the occasion on different dates. The Army and Navy also adopted resolutions and regulations for Decoration Day so that American bases across the globe could celebrate the day with proper formality.

Most cities continued to honor the original spirit of the day by decorating graves, which grew to include not just Civil War Soldiers, but also those who died in World War I and II. People even honored those who gave their lives in service of others, such as the Red Cross. In 1919, the Red Cross sent volunteers to Serbia to treat the worst typhus epidemic in history. Many of the humanitarian aid workers lost their lives fighting the disease. In honor of their selfless service, their graves were included in Decoration Day ceremonies alongside the fallen Soldiers and Sailors. Many cities also organized parades, made speeches at the cemeteries, and waved American flags for the holiday.

Grave of American Red Cross volunteer Capt. Harold V. Aupperle decorated by fellow Red Cross workers, circa 1920. Library of Congress

As Decoration Day grew in scale and importance, it spawned the creation of several symbols now associated with remembrance and Memorial Day. Two of the most famous are the red poppies and the bugle call known as “Taps.” During World War I, Col. John McCrae of Canada served in Flanders, Belgium as a surgeon. He wrote a poem based on his experiences there, in particular the sight of rows upon rows of Soldiers’ graves covered in bright red flowers:

“In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly.

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.”

The poem, “In Flanders Fields,” was published in a British magazine in 1915, where it caught the attention of two women: Anna E. Guerin of France and Moina Michael, a Georgia native. They sold artificial flowers in order to raise money for orphans and those left penniless by World War I. By 1920, the poppy was a well-recognized symbol of remembrance in America, Canada, and Europe. Michael petitioned the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) organization for help with the nationwide sales of poppies. The VFW agreed and even adopted the red poppy as its official flower for remembrance in 1922. Due to a shortage of artificial poppies made in France, Americans had to turn to other sources for the flowers. A factory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was founded to produce the artificial flowers and employed military veterans to make them. Thousands of veterans and service organizations continue to make red poppies for Memorial Day today and the donations are used to support the families of fallen Soldiers.

The second symbol of Memorial Day is the song “Taps,” perhaps more familiar from its usage at memorial services and funerals.

“Taps” sheet music. U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs

The Army first used bugle calls to signal troops and provide a means of communication across the battlefield. In 1862, Maj. Gen. Daniel Adams Butterfield worked with his brigade’s bugler, Oliver Willcox Norton, to create a new version of the “Extinguish Lights” call which signaled the roll call at the end of the day. Butterfield and Norton adapted an earlier bugle call that had fallen out of use, creating the iconic 24-note melody. Butterfield used it to honor his casualties during the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, and the call spread swiftly through the Army of the Potomac. By 1891, the U.S. Army Infantry Drill Regulations required “Taps” to be played at military funerals. It is still used at U.S. Army bases to signal lights out every evening and, in 2012, Congress declared “Taps” as the “National Song of Remembrance.”

Decoration Day parade on Fifth Avenue at the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Riverside Park, New York City, May 30, 1917. Library of Congress

In 1968, Congress passed the National Holiday Act declaring Decoration Day a national holiday. The act changed both the date and the name of the holiday, turning it into the Memorial Day celebrated today. In order to give federal workers a three-day weekend, Congress shifted the day to the last Monday in May. In 2000, Congress passed another act adding a “National Moment of Remembrance” to Memorial Day ceremonies. The act asked each American “to voluntarily and informally observe in their own way a Moment of remembrance and respect, pausing from whatever they are doing for a moment of silence or listening to ‘Taps’.” Observed at 3 p.m. local time, the National Moment is a minute of silence in honor of America’s fallen Soldiers.

Nowhere is Memorial Day celebrated with more solemnity than at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. In honor of Memorial Day, Soldiers of the 3d Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard) place flags exactly one boot-length away from each tombstone at Arlington and the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. It takes the Soldiers almost five hours to decorate the 228,000 headstones. The tradition, known as “Flags-In,” has been observed since the Old Guard was designated as the Army’s ceremonial unit in 1948.

A Soldier from the 3d Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard) places a flag in front of a gravestone in Arlington National Cemetery as part of Flags-In, May 23, 2019. Elizabeth Fraser | Arlington National Cemetery

From the graves of the Civil War to the bugle calls at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Memorial Day has its origins in the American desire to remember its heroes. More than 150 years have passed since the first flowers lay on the graves of Soldiers at Cold Harbor, Shiloh, and Charleston, sparking a long tradition of honoring those who gave their lives for their country. This Memorial Day, take time to reflect and remember those Servicemembers who sacrificed their lives for their country.

Megan Willmes

Education Specialist

Sources

Arlington National Cemetery. “Ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery.” Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Visit/Events-and-Ceremonies/Ceremonies.

American Battlefield Trust. “10 Facts: Cold Harbor.” Accessed March 18, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/10-facts-cold-harbor.

Clinton, William J. “White House Program for the National Moment of Remembrance.” May 3, 2000. https://www.usmemorialday.org//national-moment-of-remembrance.

Howard, Brian Clark and Sydney Combs. “The Facts behind Memorial Day’s Controversial History.” National Geographic, May 22, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/memorial-day-1.

Library of Congress. “Today in History – May 30.” Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/may-30/.

Lively, Mathew W. “John A. Logan and the Origins of Memorial Day.” Civil War Profiles (blog), May 27, 2013. https://www.civilwarprofiles.com/john-a-logan-and-the-origins-of-memorial-day/.

National Cemetery Administration. “Memorial Day Order.” Last modified July 20, 2015. https://www.cem.va.gov/history/memdayorder.asp.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. “Memorial Day.” Accessed March 7, 2021. https://history.army.mil/html/reference/holidays/memday/index.html.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “The Flower of Remembrance.” Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/flower.pdf.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “Memorial Day History.” Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, March 18, 2006. Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/speceven/memday/history.asp.

USMemorialDay.org. “History of Memorial Day.” Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.usmemorialday.org/history-of-memorial-day.

Villanueva, Jari. “24 Notes That Tap Deep Emotions: The Story of Taps.” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed March 7, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/taps.pdf.

“War Letters of Charles Chase, 1862-1864.” Special Collections Department. University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Virginia. http://www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/fellows/chdoc15.html.

Waxman, Olivia B. “The Overlooked Black History of Memorial Day.” Time, May 22, 2020. https://time.com/5836444/black-memorial-day/.