Lt. Daniel J. Kern and Karl Sieber examining the Ghent Altarpiece in the Altaussee mine. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

As the Nazis made their way across Europe during World War II, one of their secret missions was to collect European artwork. The U.S. Army, in collaboration with the Allied forces, created the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) program to reclaim these stolen art pieces and preserve them for future generations. The program, nicknamed the Monuments Men, was made up of men and women in the cultural resource field, including art historians, museum curators, archeologists, and other historic preservation professionals. Thanks to the work of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program on both the European and Pacific fronts, thousands of important pieces of art and other cultural resources were saved for future generations.

The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) was the primary organization that seized, cataloged, and stored cultural property in occupied German territories. Many of the artworks looted by the ERR were for Hitler’s proposed Fuhrermuseum. The Fuhrermuseum, to be built in Linz, Austria, was intended to showcase European art and craftsmanship. Hitler hoped to make the town the cultural hub of Europe. The ERR confiscated artwork, books, furniture, archives, silverware, or anything else of artistic value. Most of the pieces “collected” by the ERR were stolen or confiscated from Jewish owners. The ERR noted all of the items they acquired and compiled them into over 100 albums now referred to as Linz Albums. Overall, the ERR collected approximately 400,000 pieces that they stored in salt mines across Europe. Salt mines were ideal for storing art because of their consistent temperature and humidity levels. The salt mines offered the additional benefit of keeping the pieces safe from Allied bombings.

The Creation of the MFAA

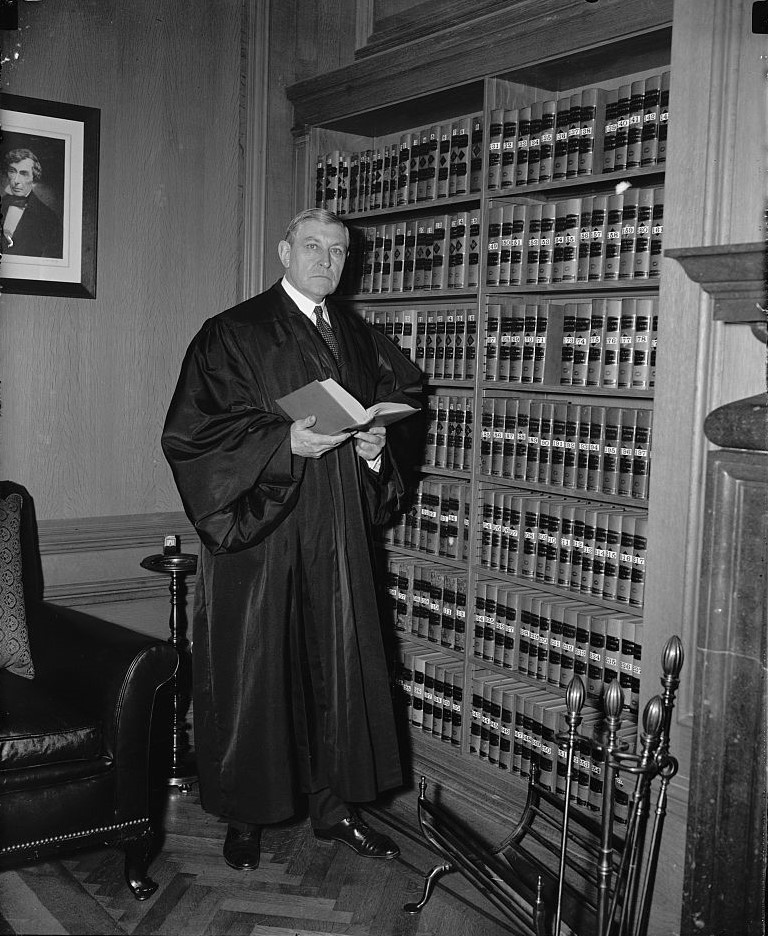

In 1942, American museum professionals grew increasingly alarmed by rumors of Nazis plundering artwork in Europe. Representatives from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York approached Supreme Court Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone with a proposal. Stone, a National Gallery of Art board member, had a long-standing interest in art. They proposed a commission to protect European cultural heritage from damage and looting. The American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Historic and Artistic Monuments in War Areas was established by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on Aug. 20, 1943. It was also known as the Roberts Commission, after its chair Supreme Court Justice Owen Josephus Roberts. The Commission’s goal was to protect European cultural and historic resources from war damage and return stolen items. The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) section was created by the Commission and assigned to the U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Military Government Division.

Justice Owen J. Roberts, May 2, 1938. Library of Congress

Careful consideration went into the selection of the MFAA members. Members were to

“record and assess war damage suffered by historic monuments prior to our occupation; take or advise the steps necessary to prevent further deterioration; supervise and pass estimates for repairs. Prevent damage by troops; affix notices, close buildings or procure guards; check billeting; interest the troops by lectures or otherwise; and investigate charges of wanton damage brought against the Allied troops and report proved cases. Prevent the looting, sale, or removal of objects of art. Establish the fact of looting by enemy troops.”

Most had backgrounds in cultural resource management. As civilians, they were archeologists, art historians, museum professionals, educators, or experts in their respective fields. Members like Capt. James J. Rorimer, Sgt. Samuel Rosenbaum, and Lt. Frank P. Albright were established museum professionals when they joined the MFAA.

On the ground, the MFAA initially had no fundamental structure. There was no chain of command or training for Soldiers who became members. U.S. Navy Lt. Cmdr. George Stout, an expert in the conservation field, created a MFAA handbook of essential skills. Stout’s experience was a valuable asset to the team since art conservation was still in its infancy. Stout noted that men arrived out of the blue with their transfer papers. The Monuments Men also lacked any enforcement authority. While they served as advisors on cultural resources, they had no authority to enforce recommendations or policy.

Thanks to intelligence work, the MFAA members located major ERR collection points. On April 6, 1945, the Army discovered the Merkers mine complex system in Thuringia, Germany. The mine contained 100 tons of gold bullion in addition to artwork in a chamber 2,100 feet below the surface. The collection included Greek and Roman art pieces, original woodcuts by Alfred Durer, and a Peter Paul Rubens painting. All were carelessly thrown into crates. Senior leaders gave the MFAA one month to inspect the artwork. Despite challenges, Stout and the other Monuments Men at Merkers evacuated the artwork from the mine before their deadline.

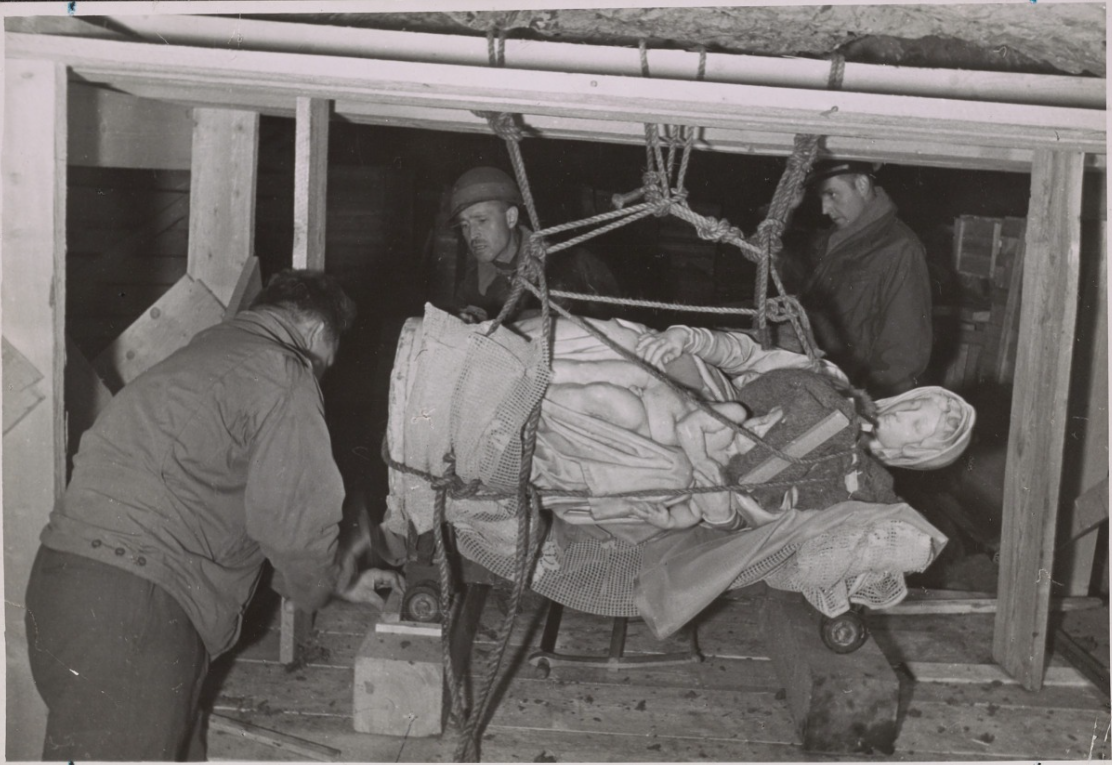

1st Lt. Stephen Kovalyak, Lt. Cmdr. George Stout, and Lt. Cmdr. Thomas Carr Howe transporting Michelangelo’s sculpture Madonna and Child from the Altaussee Salt Mines, July 9, 1945. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Other discoveries included looted artwork in a castle at Neuschwanstein and the Altaussee Salt Mines in the Austrian Alps. At Altaussee, the MFAA found the “Ghent Altarpiece” by Jan Van Eyck and Michelangelo’s “Madonna.” When the MFAA entered the mines, they counted

“6,577 paintings, 2,300 drawings or watercolors, 954 prints, 137 pieces of sculpture, 129 pieces of arms and armor, 79 baskets of objects, 484 cases of objects thought to be archives, 78 pieces of furniture, 122 tapestries, 1,200-1,700 cases apparently books or similar, and 283 cases contents completely unknown.”

The MFAA worked tirelessly on both fronts to ensure that all art and other cultural resources would be protected throughout the war.

The Monuments Women

Capt. Edith Standen and Capt. Rose Valland with art at the Wiesbaden Collection point, May 1946. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Women played an essential role in the MFAA. While the MFAA grew to over 300 members, the number of women in the division was never higher than a few dozen. The most well-known being French Capt. Rose Valland. At the outbreak of the war, Valland worked at the Jue de Paume in Paris. Upon the Nazi occupation of Paris in October 1940, the ERR took the Jue de Paume as their headquarters. Valland was instructed by Jacques Jaujard, director of the French National Museums, to stay at her current post at the museum. There she collected information on ERR plans and took meticulous notes about shipment and art storage locations. Following the liberation of Paris, Valland shared her notes with Capt. Rorimer. Her work led to the MFAA uncovering 20,000 pieces hidden in Neuschwanstein Castle. Valland later enlisted in the French Army and continued to work with the MFAA. She received the United States Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1948.

American women in the MFAA were members of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) or the later Women’s Army Corps (WAC) who applied for a position on the team. Three notable members were Maj. Mary J. Regan Quessenberry, Ardelia Ripley Hall, and Capt. Edith Standen. Quessenberry earned a degree in art history and art from Radcliffe College and traveled the world as a Radcliffe Scholar. She worked as a high school art teacher until enlisting in the WAAC in 1942. In 1943, Quessenberry was assigned to the 8th Air Force under the command of Gen. James “Jimmy” Doolittle. She learned how to assess bomb damage from air raid photographs and helped advise future air raids away from cultural landmarks. After victory in Europe, Quessenberry joined the MFAA. In 1945, she was promoted to Fine Arts Specialist Officer and worked beside Valland and Standen to repatriate pieces back to their original owners. She was promoted to MFAA Arts Intelligence subsection as an art intelligence resource office a year later.

Many women shared similar frustrations about the MFAA’s organization and mission. While their goal was to stop the looting, members were advised to turn a blind eye in cases of American looting. Evelyn Tucker, an MFAA administrator, was terminated due to her refusal to ignore the issue. Tucker’s field reports listed offenses by members. She believed these offenses ignored the organization’s goal and tarnished the United States Army’s reputation.

In 1945, the MFAA program had a major scandal. On Nov. 6, the Wiesbaden Collections Center received a telegraph that read, “immediate preparations be made for prompt shipment to the U.S. of a selection of at least two zero zero (200) German works of art of greatest importance.” The pieces were sent to the National Gallery of Art. The art included German pieces in addition to influential European artworks including Titan, Diego Velasquez, and Johannes Vermeer. The MFAA were unable to stop the possible shipment. Standen, an officer-in-charge at Wiesbaden, described how members felt about the situation saying “the state of utter misery we are all in now.” If they didn’t comply with order, they would be court marshaled. In response, 35 members of the MFAA were invited to protest against this shipment in a document that is now referred to as the Wiesbaden Manifesto. Twenty-four signed the Manifesto with Standen being the only woman. Five other members agreed to support the protest but were unable to sign the document and three other members were unable to be reached in time. The Wiesbaden Manifesto was never sent to the Army to protect the signers. The art was shipped to D.C., hung in the National Gallery of Art, and eventually toured the United States. In 1946, the Manifesto was published in the January issue of College Art Journal and sparked discussion about the ethics of this decision. All 202 pieces were returned to Germany in 1949.

Legacy of the Monuments Men

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, General Omar Bradley, and Lt. Gen. George Patton, Jr., inspect stolen art treasures. National Archives

The work of the MFAA would not be known if it were not for the work of Ardelia Hall. Hall joined the Office of Strategic Service (OSS) with an extensive knowledge of Asian Art. She transferred to the U.S. Department of State’s Office of International Information and Cultural Affairs as a Fine Arts and Monuments Adviser in 1946. The Roberts Commission had been recently disbanded, and the Department of State took over their former responsibilities. Hall, an advocate for returning looted artwork, published the findings of the Roberts Commission to encourage museums and other cultural institutions to be on the lookout for stolen items. Thanks to this, 66 cultural institutions across the country alerted the State Department of 1,600 pieces. Hall actively reviewed the information collected by the Roberts Commission and the MFAA. Her work organizing the collection ensured the Monuments Men and their work would be remembered for generations. The Ardelia Hall Collection is now housed in the National Archives. The collection includes MFAA field reports, Roberts Commission documents, and 50,000 photographs from the Munich Collection Point which would have been lost to history if not for the maintenance work done by Hall.

The legacy of the MFAA is remembered and recognized by many cultural institutions. After the MFAA program was moved to the State Department, the members helped form the Monuments Men Foundation to continue their work and legacy. The Foundation still has an existing relationship with the Army Civil Affairs office and teaches Soldiers about the significance of their work in protecting cultural resources. The story of some of the Monuments Men was memorialized in the book “The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History” by Robert Edsel. The book was then adapted into the 2014 movie, “The Monuments Men,” which generated new interest in the work of the program.

In the same year the Monuments Men were presented with the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is awarded to persons or groups whose achievements have made major or longstanding impacts on American history and culture. In a ceremony at the United States Capitol, then House Speaker John Boehner said of their accomplishments, “This small group of people who, acting purely on their own passion and courage, reclaimed the world’s most valuable treasures … they reattached the tendons to the bone that is a civilization’s identity.” Due to the work of the men and women of the MFAA, many significant cultural resources that could have been lost forever remain to this day. Their work in cultural resource management and preservation allowed a renewed focus on preservation and inspired others to become conservators.

Ellora Larsen

Education Specialist

Jennifer Dubina

Museum Educator

Sources

“Ardelia Ripley Hall (1899-1979).” Monuments Men and Women Foundation. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.monumentsmenfoundation.org/hall-ardelia-r.

Bradsher, Greg. “Edith A. Standen: A ‘Monuments Man’ in Germany 1945-1947.” The Text Message (blog). National Archives. January 2, 2014. https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2014/01/02/edith-a-standen-a-monuments-man-in-germany-1945-1947/.

Bradsher, Greg. “Before She Became The Ardelia Hall of the Department of State, Part I: Miss Hall and the Office of Strategic Services.” The Text Message (blog), National Archives. July 15, 2014. https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2014/07/15/ardelia-hall-part-i/.

Bradsher, Greg. “Before She Became The Ardelia Hall of the Department of State, Part II: Miss Hall as Consultant with the Department of State.” The Text Message (blog), National Archives. July 17, 2014. https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2014/07/17/ardelia-hall-part-ii/.

Bompane, Molly. “The Art of War and the War of Art.” U.S. Army. June 16, 2010. https://www.army.mil/article/40945/the_art_of_war_and_the_war_of_art.

Coles, Harry L. and Albert K. Weinberg. “Chapter XXXI The Protection of Historical Monuments and Art Treasures.” Last modified February 18, 2004. https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/civaff/ch31.htm.

“Edith A. Standen (1905-1998).” Monuments Men and Women Foundation. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.monumentsmenfoundation.org/standen-capt-edith-a-wac.

Edsel, Robert M. The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. New York: Center Street, 2009.

“Linz Album.” Monuments Men and Women Foundation. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.monumentsmenfoundation.org/linz-album.

McWhinnie, Bryce. “Defiant in the Defense of Art.” Prologue. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/files/publications/prologue/2015/summer/defense-art.pdf.

Morrison, Jim. “The True Story of the Monuments Men.” Smithsonian Magazine. February 7, 2014. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-monuments-men-180949569/.

“Records of the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas (The Roberts Comission), 1943-1946.” Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/microfilm/m1944.pdf.

Romero, Amanda. “The MFAA in World War II,” Ibid: A Student History Journal 9, (2015). https://twu.edu/media/documents/history-government/The-MFAA-in-World-War-II-Ibid.-Volume-9-Spring-2015.pdf.

“Rose Valland (1898-1980).” Monuments Men and Women Foundation. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.monumentsmenfoundation.org/valland-capt-rose.

Scheaffer, Erin. “Monuments Men: Preserving Cultural Heritage During a Period of Great Turmoil.” The National WWII Museum. May 28, 2020. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/monuments-men.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg: A Policy of Plunder.” Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/special-focus/offenbach-archival-depot/einsatzstab-reichsleiter-rosenberg-a-policy-of-plunder.