The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion stands in formation in front of WAC quarters in Birmingham, England, Feb. 15, 1945. National Archives

In the waning months of World War II, the 855 women of color who comprised the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion — 824 enlisted Soldiers and 31 officers — completed a time-sensitive mission in the European Theater of Operations. Army leadership believed their success would be key to boosting morale amongst the 7 million war-weary American service members, U.S. Government personnel, and Red Cross workers stationed throughout Europe in 1945. The mission? To label, sort, and clear millions of pieces of mail — including letters, photographs, and gifts — that had been stockpiled and left languishing in warehouses for months, even years. One general predicted it would take six months to process the massive backlog of undelivered mail, yet the battalion, nicknamed “Six Triple Eight,” managed to do it in just three.

The story of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion is a tale of adventure, hard work, and success against the odds. But it is also one of incredible resilience and perseverance in the face of deeply entrenched racial and sex inequality. Though many of the women of the 6888th joined the Army for the opportunities it offered for travel, education, and a regular paycheck, the desire for social change remained a strong undercurrent that unified the individual women into a cohesive and resilient unit. Alyce Dixon, a straight-talking former corporal with the 6888th Battalion said it most plainly as she reflected on her experience as a young woman: “We’re all human — whether black, white, red or brown, and we all have something to offer.”

The Six Triple Eight’s achievements are remarkable considering the fraught social and political climate of the time. Indeed, the women of the 6888th Postal Directory Battalion proved to be pioneers in military service during an era when racial segregation was law, and few opportunities were available to women to work outside the domestic sphere.

Race and Sex

Although Black men have served in the Army since the Revolutionary War, until World War II Black women were virtually excluded from military service. Beginning in 1901, white women were officially accepted into the Army as part of the Army Nurse Corps. Black nurses, were all but excluded from service. Only a handful served in the Army during the 1918 flu epidemic. Several attempts had been made to create space for white women in other military roles shortly after women earned the right to vote in 1920. However, bills introduced in the House of Representatives in 1926 and then again in 1931 supporting women’s right to serve were roundly rejected. It was not until World War II that the tides changed for women in military service.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, suddenly accelerated the War Department’s plans for a women’s corps. The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was signed into law on May 15, 1942. Fourteen months after the creation of the WAAC, it was converted to the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), which granted women full military status, rank, and benefits. Due to segregation policies in the U.S. military at the time, Black WACs could only constitute up to 10% of the overall force. Although the United States’ entry into World War II ultimately provided the needed impetus for the creation of the WAAC/WAC, important groundwork had been laid in the years prior to World War II by tireless advocates of racial equality.

Advocates and Leaders

National organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and influential Black leaders were instrumental in ensuring a place for African American women in the armed services at the outset of World War II. One such leader, Mary McLeod Bethune — educator, community organizer, public policy advisor, and, eventually, advisor to President Franklin Roosevelt — worked tirelessly in this regard. When the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) was excluded from a conference of the Women’s Interest Section on the War Department in 1941, for example, Bethune protested to the Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson in a scathing letter:

“We are anxious for you to know that we want to be and insist upon being considered a part of Our American democracy, not something apart from it. We know from experience that our interests are too often neglected, ignored or scuttled unless we have effective representation in the formative stages of these projects and proposals … We are incensed!”

The War Department reversed its decision and invited the NCNW to participate in the conference. Yet similar situations continued to arise, where the national interests of African American women were often carelessly sidelined or worse, deliberately ignored. Thus, the importance of Bethune’s influence on some of the highest-level policymaking throughout the 1930s and 1940s cannot be overstated. Ultimately, Bethune was responsible for recruiting the woman who would become the highest-ranking African American Army officer during World War II: Charity Adams.

Charity Adams U.S. Army

Adams, a teacher who had been taking summer classes at The Ohio State University in 1942, was invited to apply for entry into the WAAC. In July 1942, Adams reported to Fort Des Moines, Iowa to train in the first WAAC officer training class. Despite living and training in a segregated environment, Adams excelled. She graduated in August 1942 and led the 3rd Company, 3rd Training Regiment, made up of two white and one Black platoons. Stationed in Fort Des Moines until 1944, she worked as a station control and staff training officer. The Army promoted her to major in 1943, making her one of the highest-ranking female officers at the fort and in the nation. In December 1944, Adams was given command of the 6888th Central Postal Battalion. Following, her overseas service Adams was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Capt. Charity Adams drills her company on the drill ground at the first WAAC Training Center, Fort Des Moines, Iowa, May 1943. National Archives

Patriotism and Adventure

Educational and employment opportunities remained limited for women in the 1940s, and especially so for African American women. Racial biases, segregation policies, and dehumanizing indignities, particularly in the South, created daunting barriers to women seeking jobs outside the domestic sphere. Even those who completed their education and were qualified for teaching or other professional jobs found it difficult to find appropriate positions open to them. Thus, joining the Women’s Army Corps was an attractive option for many women seeking education, economic stability, and bit of adventure. The war also offered an opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and contribute to “women’s uplift” as Bethune had called her efforts to improve the lives of Black women.

Elaine Bennett joined the WAC, “because I wanted to prove to myself, and maybe to the world, that we [African Americans] would give what we had back to the United States as a confirmation that we were full-fledged citizens.” Essie Woods joined the Army for similar reasons: “I guess we got patriotic carried away, and we enlisted. And so that’s really how it was, that feeling of wanting to do something.” Ultimately, it is estimated that 150,000 women served in the WAAC/WAC during the war, about 4% of whom were African American. While most women were placed in administrative and clerical positions, many also served as cooks, chauffeurs, and mechanics, among a wide variety of other noncombatant jobs.

Ruth Wade and Lucille Mayo service a truck at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, Dec. 8, 1942. National Archives

Segregation and Racial Bias

Once they entered service, Black WACs faced segregation, racism, and relegation. Often, the women were assigned to menial tasks, despite extensive training or education. One woman, Vera Knapp, was accepted into the WAC as in the Auxiliary Aircraft Warning Service. She underwent seven months of extra training for her new role. However, after completing training she was told that “Negro enrollment in the Aircraft Warning Service of the WAC was not presently being accepted.”

Other women documented open racism from their white superior officers. One white WAC colonel at the hospital at Fort Devens, Massachusetts was quoted as saying “I don’t want any black WACs as medical technicians. They are here to mop walls, scrub floors and do the dirty work.” This “dirty work” resulted in several Black WACs being demoted from medical technician to orderly, despite their training and background. Four women who disobeyed orders and refused to do the work of an orderly, were dishonorably discharged and sentenced to one year of hard labor. Thankfully, the Judge Advocate General Office of Boston voided the case less than a month later.

However diverse their backgrounds, members of the 6888th shared the experience of being stigmatized as women of color in a predominantly white male institution. African American men and (later) white women were regularly deployed overseas, but Black WACs were excluded from such assignments until the War Department acquiesced to political pressure specifically aimed at this omission.

Training and Preparation

Political motives alone, however, do not explain the excitement these women felt about going overseas. Many were still in their teens and twenties and had experienced little outside their hometowns or home states, and so they were eager to see another part of the world.

Members of the 6888th assembled at the Extended Field Service Battalion, Third WAC Training Center, Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, to receive training and to be outfitted for overseas duty. Training was comprehensive and intense. Gladys Carter remembers, “We had to climb ropes … and come down the side of a ship as would if it were sinking. We had to do some crawling under wire … We had to put on gas masks … So that was part of it. A lot of marching and just getting ready, getting outfitted, that kind of thing.” However, none of the women were told what their assignments would be, where they were going, or when they were going to leave.

All of the women thought highly of their battalion commander, Maj. Charity Adams. Even if they had not trained under her, they knew of her because she was one of the two highest-ranking African American women in uniform at that time. After Battalion Commander Charity Adams and her executive officer Capt. Abbie Noel Campbell’s departure to Europe, members of the 6888th followed in two waves.

Mission Accomplished

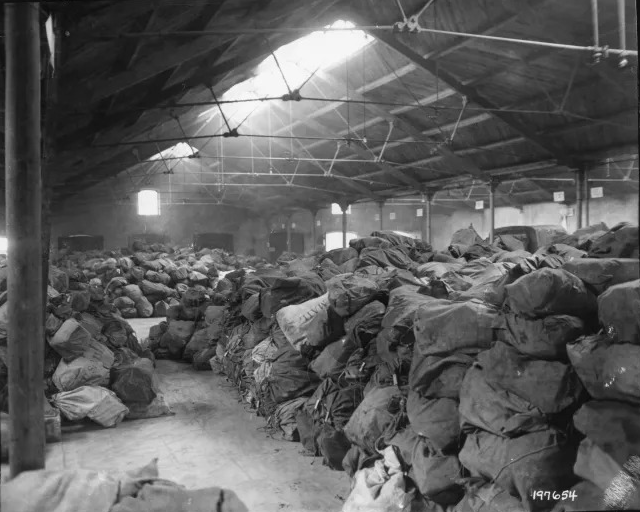

“One of the two similar buildings, in France, which house the vast quantities of mail en route to American soldiers.” The 6888th would sort similar piles. National Archives

The first contingent of nearly 700 Black WACs departed on the ship Ile de France on Feb. 3, 1945, and arrived in Glasgow on Feb. 11. From there, the women traveled to Birmingham, England by train. Nearly two months later, the second contingent of WACs arrived in England. Conditions were harsh in Birmingham, with the women working around the clock in three eight-hour shifts in the cold and dimly lit warehouses where several million pieces of mail were stacked from floor to ceiling. Some of the mail was mildewed or had been picked over by rats looking for the bits of food that had been wrapped and sent by loved ones to their Soldiers overseas. To process the mail, the Soldiers updated and maintained millions of locator cards containing the serial numbers and location of all American personnel stationed in Europe. They became detectives searching envelopes for clues to determine the intended recipient. As Adams recalled, “after a few weeks on the job some of the women had developed great skill in putting the packages back together.”

After clearing the mail in Birmingham, the Six Triple Eight transferred to Rouen, France shortly after V-E (Victory in Europe) Day. There they again dug into the task of sorting letters and preparing the mountain of backlogged mail for delivery. Of their mission, Myrtle Rhoden recalled, “We found the same condition in France that we had found in England; the mail had been held up for months … There was mail that was two or three years old.” In France, the women worked alongside French civilians and German POWS to accomplish their objective. The new recruits found the work challenging as non-native English speakers. Despite the challenge, the woman cleared the backlog in five months.

WACs and French civilians sort packages at the 17th Base Post Office. Paris, France, Nov. 7, 1945. National Archive

The arrival of a significant number of American women on the continent attracted the attention of both white and Black servicemen, who “suddenly found that they had business in Rouen,” according to Adams. Of their time in France, Adams further recalled, “we enjoyed visiting the other towns and villages … there were all sorts of festivals …” The unit was also able to participate in recreational activities including tennis, ping pong, softball, and basketball.

Next the unit was sent to Paris in October 1945 to continue the same work. On Feb. 27, 1946, the remaining Soldiers in the unit boarded the Claymont Victory for return to the United States. The unit was disbanded at Fort Dix, New Jersey without any further ceremony. Members of the unit received the European African Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, the Women’s Army Corps Service Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.

Social Progress and Overdue Recognition

World War II marked a turning point in the status of racial minorities and women in the U.S. armed services. The critical need for personnel during World War II was the major driving force behind overdue changes in race and sex policies in the military and other American institutions.

Their achievements may not have been celebrated with victory parades or a public recognition of their service, but their accomplishments encouraged the General Board, United States Forces European Theater to adopt the following in their study of the Women’s Army Corps:

“The national security program is the joint responsibility of all American irrespective of color or sex … the continued use of colored, along with white, female military personnel is required in such strength as proportionally appropriate …”

In recent years the Six Triple Eight has received renewed attention due to the women themselves their family members who have dedicated themselves to preserving their legacy. In 1989, Charity Adams Early published her memoir “One Woman’s Army” about her service. In addition, members have taken part in unions and public recognitions honoring their achievements. In 2018, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas dedicated a monument to the Six Triple Eight. The following year, the unit was awarded a Meritorious Unit Commendation.

In March 2022, the 855 women assigned to the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal. Signed into public law by President Joe Biden, the Six Triple Eight Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2021 recognizes the outstanding achievements of the Battalion — not only for the successful completion of their mission at the end of World War II, but for their sustained collective pursuit of racial and sex equality in the face of significant social and political barriers. Speaking of the Six Triple Eight, retired Col. Edna W. Cummings declared: “The Congressional Gold Medal is the nation’s gratitude for the 6888th Battalion and the thousands of African American women who served in the Army during World War II. Their service will never be forgotten as soldiers and trailblazers for gender and racial equality.”

On April 27, 2023, Fort Lee, Virginia became Fort Gregg-Adams in a ceremony that renamed the base after two Black officers whose struggles paved the way for a more inclusive military: Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams. Gregg, the first African American to achieve such a high rank, retired in 1981 after serving as the Army’s deputy chief of staff, logistics. At the redesignation ceremony, Maj. Gen. Mark Simerly stated, “They led with dignity, they looked the part, they maintained their composure and they led by example … In short, these two epitomize the professional qualities we seek in every leader who wears the uniform of the United States Army.”

One year later, the U.S. Army Women’s Museum on Fort Gregg-Adams opened a new exhibit on the Six Triple Eight. “Courage to Deliver: The Women of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion” was created in partnership with descendants of the unit. One speaker at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the exhibit summed up the unit’s exemplary work: “They fired no shots, and they fought no battles … And yet, their courage and their dedication achieved a different kind of victory.” Almost 80 years later, the 6888th continues to stand as a testament to the outstanding achievements of Black women Soldiers throughout U.S. Army history.

Melissa Thaxton

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Jennifer Dubina

Museum Educator

Sources

“African American Nurses in World War II.” National Women’s History Museum, July 8, 2019. https://www.womenshistory.org/articles/african-american-nurses-world-war-ii

Carlton, Morgan. “African American Women and the Women’s Army Corps during World War II.” ProQuest. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://proquest.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=66403138.

Clark, Alexis. “The Army’s First Black Nurses were Relegated to Caring for Nazi Prisoners of War.” Smithsonian Magazine, May 15, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/armys-first-black-nurses-had-tend-to-german-prisoners-war-180969069/.

“Creation of the Women’s Army Corps.” U.S. Army. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.army.mil/women/history/wac.html.

Fargey, Kathleen. “6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion.” U.S. Army Center of Military History, February 14, 2014. https://history.army.mil/html/topics/afam/6888thPBn/index.html.

Gaddy, Brittany. “Fort Lee Renamed in Honor of 2 Black US Army Trailblazers.” ABC News, April 27, 2023. https://abcnews.go.com/US/fort-lee-renamed-honor-2-black-us-army/story?id=98904204.

Martin, Eric, Sheila Abar, Washington Va Medical Center, and Alyce Lillian Dixon. Alyce Lillian Dixon Collection. 1943. Personal Narrative. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.05202/.

“The Mary McLeod Bethune Council House: African American Women Unite for Change.” National Park Service. Last updated May 12, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-mary-mcleod-bethune-council-house-african-american-women-unite-for-change-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

Michigan Women’s Historical Center and Hall of Fame, Katie Cavanaugh, Sarah E McLennan, and Essie Dell Woods. Essie Dell Woods Collection. 1943. Personal Narrative. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.04741/.

Moore, Brenda. To Serve My Country, To Serve My Race. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Phelps, Janeen R. “U.S. Army Women’s Museum Launches Exhibit Honoring 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion.” U.S. Army, April 24, 2024. https://www.army.mil/article/275623/u_s_army_womens_museum_launches_exhibit_honoring_6888th_central_postal_directory_battalion.

Sheldon, Kathryn. “A Brief History of Black Women in the Military.” Minerva’s Bulletin Board III, no. 4 (Dec 31, 1995): 6. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/brief-history-black-women-military/docview/231082169/se-2.

Thompson, Cameron. “They ‘Achieved a Different Kind of Victory.’ Army Women’s Museum is Highlighting Their Courage and Dedication.” WTVR, April 26, 2024. https://www.wtvr.com/news/local-news/army-womens-museum-courage-to-deliver-exhibit-fort-gregg-adams-april-26-2024.