This painting depicts the 442d Regimental Combat Team’s rescue of the “Lost Battalion” in October 1944. Center of Military History.

Rarely has a nation been so well served by a people it had so ill-treated…They did more than defend America; in the face of painful prejudice, they helped to define America at its best.

–President Bill Clinton

In the early afternoon of October 27, 1944, a unit of Soldiers navigated through the rugged terrain of the Vosges Forest near the border of France and Germany. For two days, they had cut a twisting and winding path through the darkness of the foliage as icy rain came down on the men. German mines and obstacles slowed their progress on the small roads and trails that led deeper into the forest. Even in the best conditions, the Vosges was tough to move through, but the Nisei Soldiers of the 442d Regimental Combat Team persevered. Just a few miles from them, the enemy had trapped and surrounded another group of Soldiers, the 141st Infantry Regiment, called the “Lost Battalion.” Isolated and cut off by the enemy, the 442d was sent to rescue them. As they approached the ridge where the Germans surrounded the 141st, enemy forces in defensive positions opened fire. Dozens of Soldiers were killed or wounded by German artillery fire, but the unit held their ground. It would take more than a few shells to stop the Nisei Soldiers of the 442d from doing their duty.

The 442d Regiment’s daring rescue of the “Lost Battalion” in October 1944 stands as just one of many accomplishments in the unit’s storied history. Composed almost entirely of Japanese Americans, the 442d is among the most decorated units of its size in American history. Yet, the United States failed to fully recognize their service, denying them medals and treating their families unjustly. While they fought their way across Europe, men like Pfc. Arthur Iwasaki, left families behind in the United States imprisoned in internment camps. Japanese Americans contributed to victory during World War II despite this unequal treatment. They upheld the Army’s core values of loyalty, duty, selfless service, and personal courage in the face of bigotry, racism, and prejudice.

Pfc. Arthur Iwasaki was drafted in March 1942. While attending basic training, his family was forcibly relocated to the Nyssa Labor Camp in Oregon. He served with the 442d in Europe, earning a Bronze Star medal. His jacket is currently on display in the Nisei Soldier Experience Gallery. Iwasaki Family.

Japanese immigrants first arrived in the United States long before World War II. From 1860 to 1910, over 400,000 Japanese immigrants settled in Hawaii and the west coast of the United States. Called Issei (the Japanese term for immigrant), they worked primarily as farmers and fisherman. They eventually established businesses and created their own communities. Due to widespread racism, Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act in 1924, which banned Asians from immigrating to the United States and denied citizenship to those already living in the country. Though the United States denied the Issei citizenship, this did not apply to their children. The Nisei (children of Japanese immigrants), were born citizens and granted all the rights that came with that title. But they were children of two worlds. On one hand, they learned from their parents about Japanese language, food, and culture. On the other hand, they attended church , spoke English, and ate traditional American food. Yet, the Nisei were also treated unequally, experiencing the same racism and discrimination their parents faced. They were physically attacked, verbally insulted, and considered sub-human by many white Americans.

A California woman points towards an anti-immigrant sign posted outside of her home. National Japanese American Historical Society.

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The surprise attack, as the United States was not at war with Japan at the time, killed over 2,400 Americans. The Japanese air raid angered and shocked Americans, and many feared that Japan might invade Hawaii or even California. This anger and fear led to Executive Order 9066. Signed on February 19, 1942 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the order allowed military commanders to remove and exclude people of Japanese descent from certain areas in the United States. Military leaders declared that Japanese Americans must leave the west coast of the United States and were given a week to leave. They left behind homes, possessions, businesses, and even pets. If they did not leave on their own, they were forcefully relocated to internment camps. Over 120,000 people lived in rough conditions, under armed guard, in the internment camps by the end of 1942.

As World War II raged around the world, many Nisei wanted to avenge Pearl Harbor and serve in the American military. However, the U.S. government classified them as enemy aliens, which disqualified them from service. This changed in June 1942, when the Army selected a group of Nisei Hawaiian National Guardsmen to serve in a special, segregated, Nisei unit. Comprised entirely of Nisei and led mostly by white officers, the approximately 1,400 men were formed into the 100th Infantry Battalion. For these Soldiers, their motivation was simple: they wanted to serve their country and prove their loyalty. Sgt. Gary Uchida, a member of the 100th simply explained, “Uncle Sam called and I answered.” To reflect their patriotism, they chose the unit motto, “Remember Pearl Harbor.”

Most Soldiers of the 100th, and later the 442d, trained at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. Those from Hawaii often brought with them their Hawaiian culture, as seen in this photo, in which a quartet of Nisei Soldier singers play the ukulele. Library of Congress.

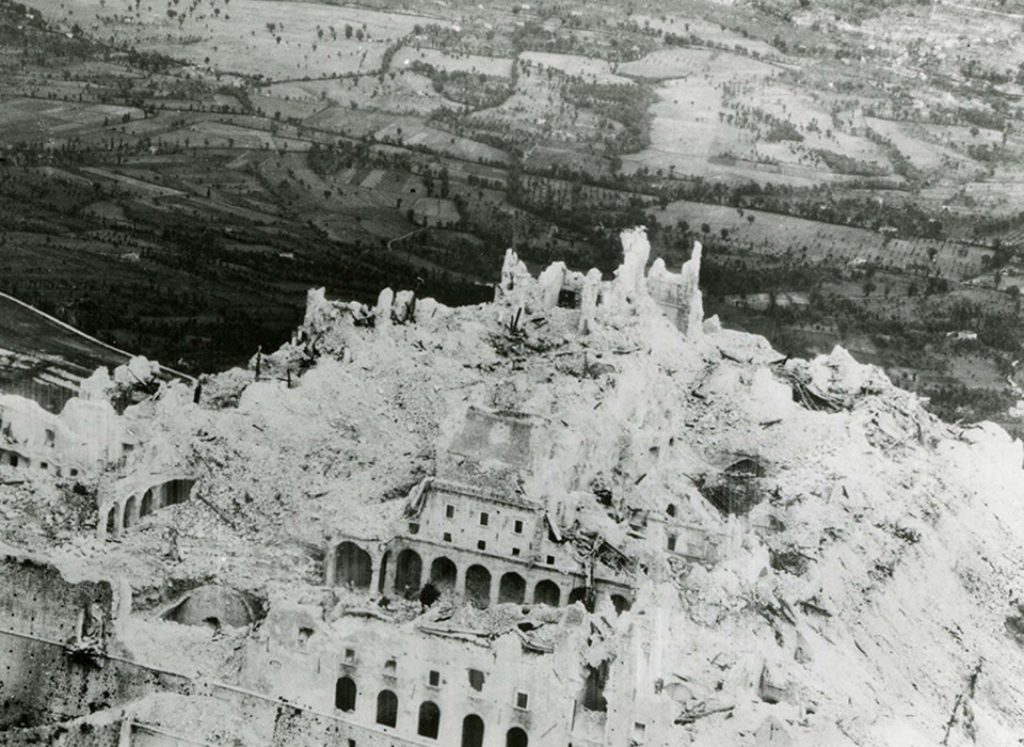

After basic training, the 100th deployed to North Africa, arriving in Oran, Algeria, on September 2, 1943 to support the Allied invasion of Italy. Most Nisei Soldiers were sent to the European Theater, as Army leadership did not trust them to fight against the Japanese. Wanting to prove their loyalty and patriotism, the men of the 100th were eager for combat. They deployed to Italy on September 19, and soon engaged with the enemy near Salerno. In 24 hours, they drove the Germans back 15 miles and captured the town of Benevento. Over the next months, the men of the 100th distinguished themselves in combat. Their bravery and effectiveness surprised many white officers but they suffered heavy casualties. Of the 1,300 men of the 100th to deploy to Italy, only 521 remained by March 1944, earning them the nickname “The Purple Heart Battalion.”

An American plane captures the ruins of a historic abbey following the Battle of Monte Cassino. The 100th participated in the Allied victory, which took months of heavy fighting. National World War II Museum.

The War Department realized that an entire regimental combat team of Nisei Soldiers should be formed due to the discipline, loyalty, and effectiveness of the 100th. President Roosevelt announced the formation of the new unit, the 442d Regimental Combat Team, declaring, “Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry.” The unit was activated on February 1, 1943, consisting of only Nisei recruits who completed a required survey. In this survey, recruits were required to prove their loyalty to the United States, despite the fact that they had been American citizens their entire lives. The draft was used to recruit for the unit, with some Soldiers coming from internment camps where they had lived with their families. They trained for over a year before deploying to Italy to join the 100th, arriving at Anzio, Italy, on May 28, 1944. The 100th merged with the 442d, acting as one of the unit’s three infantry battalions, but retained their unit name.

The 442d’s first major battle as a complete unit occurred on June 26, 1944, at the Italian town of Belvedere. Held by a battalion of highly trained German troops, the 442d attacked in force. While other elements occupied the enemy’s attention, the 100th attacked the right flank and overwhelmed the Germans there. In just a few hours, the outnumbered men of the 100th destroyed a German battalion and captured the town, losing only 11 men. For their incredible feat, the 100th received a Presidential Unit Citation, the first of many.

Over the next months, the 442d participated in combat operations around Rome. The Allies captured Rome on June 4, 1944, and the 442d was redeployed to France. Attached to the 36th Infantry Division, the 442d fought to liberate the French towns of Bruyeres and Biffontaine from the Germans. They fought in a series of brutal engagements from October 18-23, fighting at times from house to house. Casualties were heavy but the 442d succeeded in liberating the towns. After only two days of rest following weeks of constant activity, the 442d received their mission to save the “Lost Battalion.”

The men of the 442d march down a road as they prepare for the offensive to save the “Lost Battalion.” National Archives.

As the weary Soldiers of the 442d endured an artillery barrage from the fortified enemy position, they prepared to attack. Enemy machine gun nests, firing positions, and mines dotted the ridge. The 442d attacked these defenses several times yet were unable to break through. On October 29, with the “Lost Battalion’s” situation growing worse, the 442d decided to assault the enemy positions. While moving against a German position on Hill 617, Pvt. George Sakato charged a German machine gun after enemy fire killed a fellow Soldier. Sakato single-handedly killed 12 enemy soldiers, wounded two, and captured four prisoners. Similar actions of valor and sacrifice were made across the battlefield and finally the 442d broke through to the “Lost Battalion” on October 30. Their victory came at a steep cost as the 442d suffered over 800 casualties in just a few days.

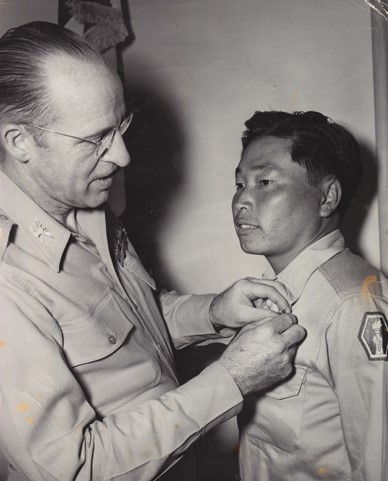

Pvt. George Sakato is awarded the Distinguished Service Cross by Col. John Campbell for his actions at Hill 617. This recognition was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 2000. Sakato’s helmet is currently on display in the Nisei Soldier Experience Gallery. Sakato Family.

The 442d continued to serve with distinction through to the end of the war. They guarded a section of the French-Italian border and participated in the Po Valley Campaign, helping to break the German Gothic Line in April 1945 after weeks of heavy fighting. On May 7, 1945, Germany surrendered and the war in Europe ended. In less than ten months of fighting as a complete regiment, the 442d compiled an impressive record of battlefield achievements. The 14,000 Nisei Soldiers who served in the 442d were awarded 18,143 awards, including seven Presidential Unit Citations. Despite their triumph in battle, Army leadership did not fully recognize their achievements, denying them many awards that white Soldiers would have received for similar accomplishments.

For decades after World War II, Japanese American activists worked to ensure that Nisei Soldiers and Japanese Americans received fair credit for their military service and reparations for their internment. The 442d, along with the Nisei Soldiers who served in the Military Intelligence Service, acted as a powerful example of Japanese American loyalty, convincing many white Americans to treat Japanese Americans better. One of the first to fully acknowledge the service of the 442d was the state of Texas. In 1962, Governor John Connally announced that the veterans of the 442d were “Honorary Texans” for saving the lives of hundreds when they rescued the “Lost Battalion.” In 1976, President Gerald R. Ford officially rescinded Executive Order 9066 and in 1980, President Jimmy Carter established a commission to investigate Japanese American internment. Released in 1982, the report concluded that there was no satisfactory reason to incarcerate over 120,000 people, and recommended that the United States issue an official apology and provide payments to those who were imprisoned.

President Clinton awards Senator Daniel K. Inouye with the Medal of Honor on June 21, 2000. Inouye, a 442d Soldier, led an assault against an enemy position, in which he lost his arm to an enemy grenade. He went on to serve as the first Japanese American congressman, representing Hawaii in Congress for more than 50 years. United States Government.

President Clinton awards Senator Daniel K. Inouye with the Medal of Honor on June 21, 2000. Inouye, a 442d Soldier, led an assault against an enemy position, in which he lost his arm to an enemy grenade. He went on to serve as the first Japanese American congressman, representing Hawaii in Congress for more than 50 years. United States Government.

On June 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded the Medal of Honor to 20 Soldiers of the 442d, with seven of them going to surviving veterans. Sakato attended the ceremony and accepted the award from Clinton, stating afterwards, “As a unit we were used like cannon fodder…I was willing to die for my country.” The sacrifices and courage of Sakato, along with thousands of other Nisei Soldiers, perfectly embodied the spirit of the Army’s values. They were loyal to the United States, courageous in battle, dutiful to their commanders, and selfless in their devotion to each other. They served while many of their family members, friends, and fellow citizens were kept under armed guard by the country they served. They helped change the United States with their powerful example, illustrating that Japanese Americans were just that, Americans.

A. J. Orlikoff

Lead Education Specialist

Sources

Bamford, Tyler. “Medal of Honor Recipient Daniel Inouye Led a Life of Service to His Country.” National World War II Museum. July 19, 2020. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/medal-of-honor-recipient-daniel-inouye.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1982. https://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/justice-denied.

Crost, Lyn. Honor by Fire: Japanese Americans at War in Europe and the Pacific. Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1994.

Odo, Franklin. “100th Infantry Battalion.” Densho Encyclopedia. Last modified October 16, 2020. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/100th_Infantry_Battalion/.

Odo, Franklin. “442nd Regimental Combat Team.” Densho Encyclopedia. Last modified October 16, 2020. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/442nd_Regimental_Combat_Team/.

Gentry, Connie. “Going for Broke: The 100th Infantry Battalion.” The National World War II Museum. August 1, 2020. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japanese-american-100th-infantry-battalion.

“Rhineland Campaign-Vosges (September 15 – November 21, 1944): 100th/442nd RCT and the Rescue of the ‘Lost Battalion,’ October 1944.” Accessed February 26, 2021. https://www.goforbroke.org/learn/history/combat_history/world_war_2/european_theater/rescue_of_the_lost_battalion.php.

Gentry, Connie. “Going For Broke: The 442nd Regimental Combat Team.” The National World War II Museum. September 24, 2020. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/442nd-regimental-combat-team.

Laurie, Clayton D. Rome-Arno, 22 January-9 September 1944. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 2019. https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-20/index.html.

“Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II.” National Museum of American History. Accessed March 2, 2021. https://americanhistory.si.edu/righting-wrong-japanese-americans-and-world-war-ii.

“Japanese American Incarceration.” National World War II Museum. Accessed February 26, 2021. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japanese-american-incarceration.

Popa, Thomas. Po Valley, 5 April-8 May 1945. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1995. https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-33/index.html.

Additional Resources

Classroom and Research Materials:

Discover Nikkei: Japanese Migrants and Their Descendants. Japanese American National Museum. Accessed August 13, 2021. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/.

“Behind the Wire.” Library of Congress. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/japanese/behind-the-wire/.

“Japanese American Internment.” Library of Congress. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/japanese-american-internment/.

Military Intelligence Service Research Center. National Japanese American Historical Society. https://www.njahs.org/misnorcal/resources/resources_teachers.htm.

Wakamatsu, Peter K. The 442.org. Last updated February 19, 2020. http://www.the442.org/.

Articles and Publications:

McFadden, Robert D. “Daniel Inouye, Hawaii’s Quiet Voice of Conscience in Senate, Dies at 88.” New York Times, December 17, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/18/us/daniel-inouye-hawaiis-quiet-voice-of-conscience-in-senate-dies-at-88.html.

McNaughton, James C. Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service during World War II. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 2006.

Torigoe, John. “Brothers went to war, but not all on the same side.” CNN. November 10, 2011. https://www.cnn.com/2011/11/08/us/veterans-in-focus-7-brothers-world-war-ii/index.html

Videos:

“Going for Broke – Japanese Americans in World War II – Full Length Documentary.” Questar Entertainment. June 25, 2013. Video, 58:09. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_WG96MAirI.

Go For Broke! Film by Robert Pirosh. Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer. 1951.