Learning the Art of Joint Operations: Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy

[Source: “Learning the Art of Joint Operations: Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy”. Joint Force Quarterly 97, Web, March 31, 2020]

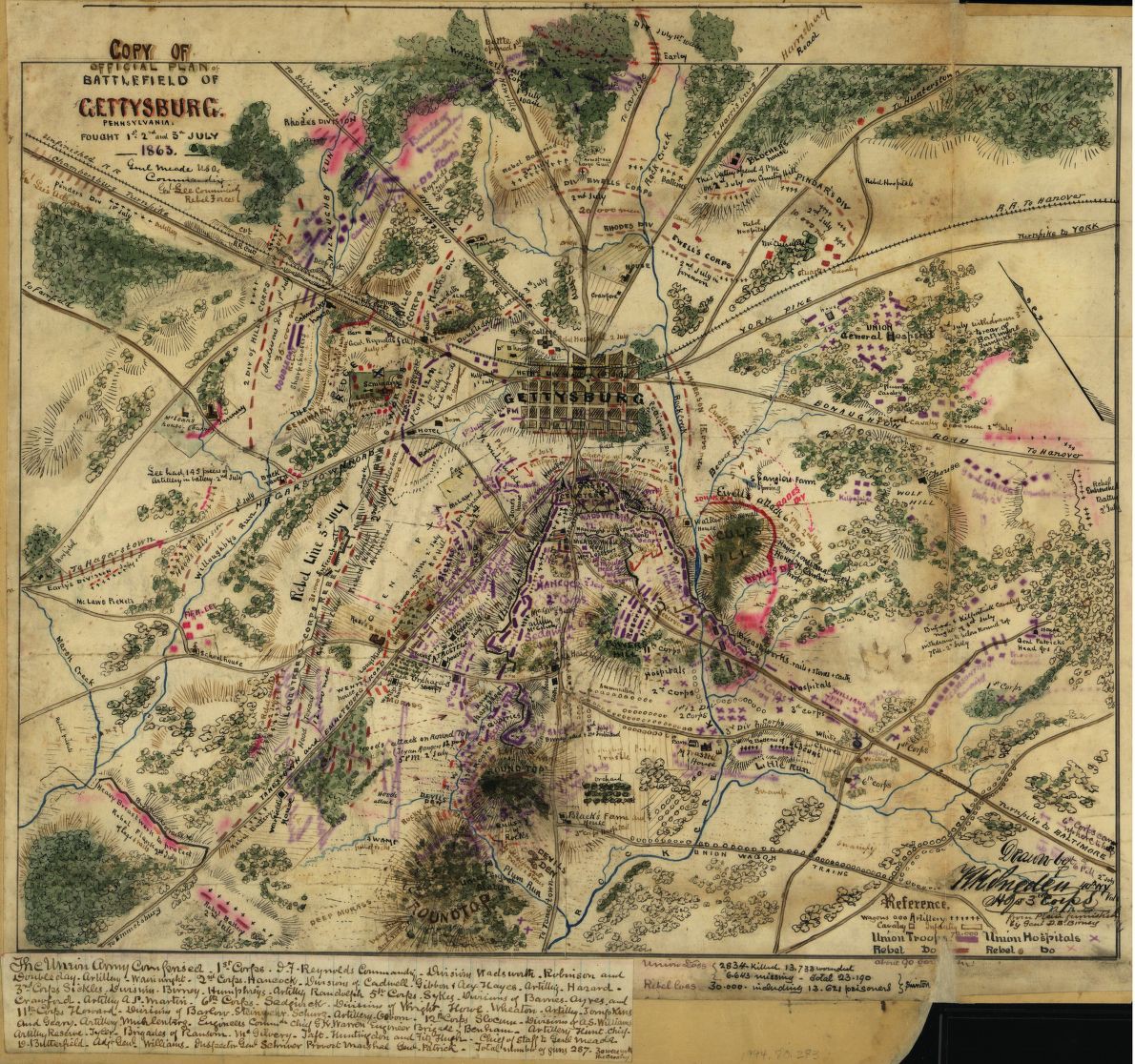

In February 1862, Major General George B. McClellan sent his appreciation to Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant and Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote of the U.S. Navy for the recent capture of Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River in Tennessee.1 Ten days earlier, the two officers and their commands had captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River, just 10 miles to the west. Confederate generals had counted on the two forts to stop Federal forces from moving south along the two rivers, both natural avenues of advance—the Tennessee reaching into the piney woods of northeast Mississippi, the Cumberland bending southeast toward Tennessee’s Confederate state capital of Nashville. With those fortifications now in Union hands, the heart of the western Confederacy was laid open to further operations by U.S. forces.

McClellan’s commendation acknowledged that the operations’ success resulted from cooperation between Grant’s land and Foote’s naval forces. While the term joint operations had not yet become part of the profession’s language, the concept was anything but new, as centuries of warriors had recognized the advantages of soldiers and sailors working together. In a practical way, the two Services have always been complementary, with armies fighting on land, seizing and occupying terrain, while navies provided transportation, sustainment, and, when possible, fire support. Effectively conducting such operations, however, presents challenges not encountered by a single Service operating alone. Among the inter-Service gaps to be bridged are differences in doctrine, technology, weapons, planning, and more abstract factors such as culture. As Milan Vego points out, joint operations are inherently complex “because of the need to sequence and synchronize the movements and actions of disparate force elements. Sound command and control can be especially challenging.”2

Vego’s observation is just as applicable to the Civil War period as it is today, if not even more so. In the mid-19th century, the principle of unity of command had not been defined, at least not formally. Today, that concept is meant to mitigate the confusion and complexity of joint operations—as Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations, points out—by assigning “a single commander with the requisite authority to direct all forces employed in pursuit of a common purpose.”3 In the 1860s, however, without such a formal directive, officers had to rely on cooperation developed through personal relationships to make joint operations work. Over the course of the war, Grant learned the art of joint operations by working with his naval counterparts to form relationships built on trust, honesty, mutual respect, and a commitment to the ultimate objective of winning the war. Such relationships do not occur by chance, as Grant learned working with Foote. Grant’s experiences in learning to cooperate with the Navy are a reminder that interpersonal relationships, inter-Service respect, and learning from one’s missteps are essential ingredients of effective joint operations.

First Battles, First Missteps

In the summer of 1861, Grant was barely back in uniform when he began working with elements of the Navy’s Western riverine fleet. During a futile search for Confederate officer Thomas Harris in July 1861, naval transports ferried Grant’s force across the Mississippi River from Illinois to Missouri. Two months later in early September, Grant and his troops occupied Paducah, Kentucky, the first Federal presence in the Bluegrass State; their transit from Cairo, Illinois, across the Ohio River was facilitated by two gunboats and three steam transports of Foote’s command.4

As summer turned to fall, Grant and naval commanders continued to communicate about simple matters such as positioning gunboats and reconnaissance operations around the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Their exchanges were professional, typically couched as requests rather than as orders. The exception was a minor dispute over control of the Graham, a “wharf boat” used for storing supplies. Grant, citing a lack of sufficient storehouses on land, first appropriated it, thereby initiating an exchange with Foote over who most needed the boat. Neither man was prepared to concede, so Foote appealed to the senior officer in the area, General John C. Frémont, for arbitration.

Resolution came when Foote and Grant together, or so it seemed, worked out a compromise to divide the ship’s space in half. Writing to Grant, Foote confirmed that the Army “will retain one half of the Boat, offices included, and we will endeavor to get on with the other half,” all “to promote conjointly the highest interest of the government.” The spirit of cooperation, however, had not in fact prevailed, as Foote revealed in a subsequent letter to Washington, DC, when he noted that Grant “would not give a place assigned . . . to our store, had it not been a positive order from Genl. Frémont.” Still new to command, and especially inexperienced in working with the Navy, Grant had yet to learn that his effectiveness as an Army commander was dependent on a working relationship with his naval peers, who controlled essential capabilities the Army itself could not provide. Nevertheless, in the midst of this tug of war, Foote wrote to naval secretary Gideon Welles that “I am on good terms with the army officers.” Less than a month later, Grant would make another misstep with Foote, from which the Soldier would come to appreciate the necessity of open communication with the Sailor.5

During the movement to and from the Battle of Belmont, Missouri, on November 7, 1861, six steamers transported Grant’s infantry across the Mississippi, while the gunboats Tyler and Lexington provided fire support. In the weeks leading up to the battle, Grant and Commander Henry Walke worked closely on the deployment of watercraft on the Mississippi River, especially the gunboats, mostly around Cairo, Illinois. When Grant decided to move against Belmont, however, communication with Walke broke down. The naval commander first learned of the operation verbally late in the evening of November 6, less than 12 hours before movement began. Grant’s written orders then arrived around 3:00 a.m., instructing Walke that the transit of troops would begin a mere 3 hours later. Walke set the Navy in motion with all possible speed, but one can imagine his frustration at the lack of prior notice. Grant, perhaps overly concerned about operational security, had withheld details until the last minute even from some of his own officers.6

Despite the short notice, Walke and his Sailors all performed proficiently and professionally before, during, and after the battle, landing the Army just north of Belmont, providing supporting artillery fire, and facilitating the Soldiers’ escape when the Confederates counterattacked. Walke was proud of his command, noting, “with what zeal and efficiency they all performed,” in spite of being “apparently new material.” Grant agreed with Walke’s self-assessment, complimenting the Navy’s “most efficient service. . . . They engaged the enemy’s batteries . . . and protected our transports throughout.” Importantly, Grant shared that praise with Walke and his Sailors, acknowledging the Navy’s participation and their essential contribution to the Army’s success.7

Captain Foote, Walke’s commanding officer, however, was less than pleased with how Grant conducted the operation—specifically, the lack of communication between Grant and himself as the senior naval officer in the area. In his report to Secretary Welles, Foote complimented the performance of the Army, stating that the horses of both Grant and General John McClernand had been hit during the fight, evidence of the officers’ courage. Nevertheless, Grant had failed to honor their agreement:

to inform me . . . whenever an attack upon the enemy was made requiring the cooperation of the gunboats. . . . No telegram was sent me, nor any information given by General Grant when the movement upon Belmont was made. . . . I deeply regret the withholding of this information from me, as I ought not only to have been informed, in order that I might have commanded the gunboats, but it was a want of consideration toward the Navy, a cooperating force with the army on such expeditions.8

Foote concluded by asking Welles either to send a more senior naval officer who would have “immunity from the orders of brigadier-general down to lieutenant-colonel, who are inexperienced in naval matters” or to promote him to the rank of flag officer, equivalent to Grant’s rank of brigadier. Welles recognized that Foote’s request was well-founded and necessary; the promotion came on November 13.9

Foote was correct in his criticism of Grant, not only for failing to follow through on their agreement, but also for a lack of consideration for a fellow officer and sister Service. Either through belated self-awareness or the prompting of another—Grant left no record of the incident—the general sought out Foote shortly after the battle and “expressed his regret that he had not telegraphed as he had promised, assigned as the cause that he had forgotten it, in the haste in which the expedition was prepared, until it was too late for me to arrive in time to take command.” The explanation was plausible, and one that Foote accepted. Grant took responsibility for the error and, more important, learned a valuable lesson about the necessity for cooperation with the Navy.10

Perhaps it was Foote’s promotion to flag officer, Grant’s new appreciation for the Navy and its capabilities, or a combination of both, that prompted Grant to modify his interactions with his naval colleagues following the battle at Belmont. From late 1861 into the first weeks of the new year, Grant’s relationship with Foote and Walke was professional, respectful, open, and honest. Consultation was the watchword for inter-Service interaction.11

Fortunately for the Union, Grant and Foote shared a commitment to the cause of which both were a part, recognizing that cooperation would advance the day of final victory. Foote believed that the Army and Navy “were like blades of shears—united, invincible; separated, almost useless,” a philosophy Grant was coming to share. And perhaps because Grant was still learning the lessons of joint operations, Foote was willing to forgive errors of initiative and aggression. The coming campaign against Fort Henry and Fort Donelson would demonstrate that Grant had indeed learned something over the previous months and that his approach for dealing with the Navy had matured.12

Lessons Learned, Lessons Applied

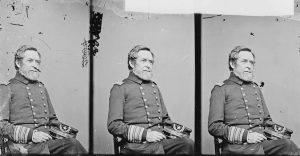

Captain Henry Walke, ca. 1861–1865 (Library of Congress/Mathew Brady)

The improved relationship between the Services paid off in mid-January when one of Grant’s subordinates, Brigadier General Charles F. Smith, reported that Fort Henry, the Confederates’ safeguard of the Tennessee River, was vulnerable. Reacting to Smith’s assessment, on January 23 Grant headed to St. Louis where he proposed to Major General Henry Halleck, the senior officer in the region, an expedition in conjunction with the Navy to seize Fort Henry. Halleck, Grant recalled, received him with “little cordiality,” and within a few minutes “cut short” the interview, “as if my plan was preposterous.” Grant returned to Cairo “crestfallen” but not cowed. The following day he telegraphed Halleck, “With permission I will take Fort McHenry [sic] on the Tennessee and hold and establish a large camp there.” Given the rebuff he had just received at the hands of Halleck, why would Grant have any expectation of a different response? Because this time, he had Foote on his side. Grant wrote later that he and Foote had “consulted freely upon military matters and he agreed with me perfectly as to the feasibility of the campaign up the Tennessee.” Arriving the same day as Grant’s telegram, a note came from Foote, informing Halleck that “General Grant and myself are of the opinion that Fort Henry . . . can be carried . . . and permanently occupied. Have we your authority to move?” With Foote now backing the idea, Halleck looked past his reservations about Grant to see the soundness of the proposal, and shortly after not only gave his blessing but also claimed to have originated the idea: “I made the proposition to move on Fort Henry first to General Grant.”13

With approval secured, on February 3 the joint force headed south on the Tennessee River. Three days later, Foote informed Secretary Welles that after a “severe and closely contested action” between his gunboats and the Confederate batteries, “the rebel flag was hauled down” as the fort’s garrison surrendered to the U.S. Navy. Grant’s infantry arrived shortly after to occupy the fort and take charge of the prisoners. For his part, Grant commended Foote’s success. Walke recalled that once the fort was secure, Grant joined him on the USS Carondelet and “complimented the officers of the flotilla in the highest terms for the gallant manner in which they had captured Fort Henry.” Grant then notified Halleck’s headquarters that “in little over one hour all the batteries were silenced and the fort surrendered.” The Army commander showed no sign of jealousy or resentment, but instead saw the Navy’s victory for what it was—a Union victory—and that was something he would celebrate, no matter who received the credit.14

The working relationship that Grant and Foote had cultivated over the preceding months had now borne fruit. Their like-minded approach to fighting the war and spirit of “consultation” had won a significant victory, and that shared perseverance would now carry them forward, specifically 10 miles to the east, where the Confederate garrison at Fort Donelson offered the next prize.

As Union infantry were settling into Fort Henry on February 6, Grant and Walke continued to cooperate by sending a joint force south on the Tennessee River to destroy a bridge on the critical Memphis, Clarksville & Louisville Railroad. The primary objective, however, was Fort Donelson, tantalizingly close on the Cumberland River where it blocked Federal access to Nashville. “I was very impatient to get to Fort Donelson,” Grant later wrote, wanting to strike before the arrival of Confederate reinforcements. He made his intentions clear when he told Halleck that he intended to move immediately on Donelson, a determination with which Foote could sympathize and willingly support, if not for the practical concerns of needing to refit his small fleet because of the damage suffered in the duel for Fort Henry.15

To undertake those repairs, Foote and most of his force returned to Cairo, where on February 10 he received a request from Grant to hurry along whatever boats he could to Fort Donelson as soon as possible. Revealing his frustrations with the campaign’s waning momentum, Grant wrote that he had “been waiting patiently for the return of the gunboats.” “I feel that there should be no delay” in moving on Donelson, he continued, but conceded the advantages, if not the necessity, of a joint operation: “I do not feel justifiable in going without some of your boats to co-operate.” If it would help “expedite matters,” Grant offered some of his artillerymen “to serve on the gunboats temporarily.” Concluding, he wrote, “please let me know your determination in this matter and start as soon as you like. I will be ready to co-operate at any moment.” Brigadier General Lewis Wallace, one of Grant’s division commanders, confirmed Grant’s hesitancy to move without Foote when he wrote that Grant “relied upon Flag-Officer Foote and his gun-boats, whose astonishing success at Fort Henry justified the extreme of confidence.”16

Despite Grant’s impatience, his emphasis on cooperation demonstrates how his manner of dealing with Foote had evolved since the previous November. Evidenced by his offer of men to serve on gunboats, he now understood that to achieve the greatest possible effects, the Army and Navy had to support each other and that he shared in the responsibility for that cooperation. He therefore sought the assistance of a co-equal, recognizing that another Service provided critical capabilities and that the sum of their combined efforts was greater than the individual components. To accomplish the mission, Grant wisely and correctly sought Foote’s commitment rather than his compliance.

Foote, who was receiving additional pressure from Halleck to get the gunboats moving up the Cumberland to Donelson, took action almost immediately on receiving Grant’s request of February 10. Orders went out to Lieutenant Seth Ledyard Phelps “that all the available gunboats should immediately proceed up the Cumberland River and in cooperation with the army make an attack on Fort Donelson.” Foote made the order despite his own reservations; he confessed to Secretary Welles, “I go reluctantly, as we are short of men. . . . [Nevertheless] I shall do all in my power to render the gunboats effective in the fight, although they are not properly manned.”17

Battle of Fort Donelson (Library of Congress/Sarony, Major & Knapp)

By February 12, Grant’s army had arrived at Donelson and took up positions that pinned the Confederate garrison against the Cumberland River. The Navy arrived the same day in the form of the Carondelet and Commander Walke, who ordered “a few shell[s] [thrown] into Fort Donelson to announce my arrival to General Grant.” Walke’s means of signaling his approach was effective, and the next morning Grant asked him to “advance with your gun boats” to divert Southern attention, while the infantry extended and strengthened its positions around the fort. Walke responded in the affirmative, and at the agreed time his gunners sent into the fort nearly 150 shells, followed by another 45 rounds later in the day. That evening Foote himself finally arrived with five gunboats to supplement the firepower of Walke’s Carondelet.18

The next day, February 14, the reunited Army and Navy commanders set their plan in motion. The joint attack, as Grant understood it, “was for the troops to hold the enemy within his lines, while the gunboats should attack the water batteries at close quarters and silence his guns.” In short, they sought a repetition of the Fort Henry operation that had proved so successful just a week earlier, but Fort Donelson presented a different challenge altogether with its higher elevation, clear sight lines toward the approaching gunboats, and determined gunners.19

At 3:00 that afternoon, Foote led forward his four ironclads abreast, with the two wooden gunboats following. In the artillery duel that followed, all the ironclads suffered significant damage, with two being disabled—including Foote’s St. Louis, which suffered a direct hit on its wheelhouse that killed the pilot and wounded Foote. The one bit of luck the Sailors had that day was the Cumberland’s current carried the damaged vessels away from the Southern batteries rather than deeper into the killing zone. Grant, who observed the fight from the riverbank, wrote of his dismay as he watched Confederate rounds repeatedly find their mark, followed by the withdrawal of Foote’s flotilla. Having witnessed the Navy’s rebuff if not defeat, he and his Soldiers were “anything but comforted.” Facing the likelihood of a lengthy siege as temperatures sank to well below freezing, Grant anticipated having “to intrench my position, and bring up tents for the men or build huts.”20

The sun had yet to crest the horizon the next morning when Grant received a note from Foote asking for a meeting aboard his flagship to discuss their course of action given the preceding day’s setback. Foote apologized for not traveling himself but explained that his wound prevented ease of movement. Grant immediately set off for the river, and if he had any doubts about the beating the Confederates inflicted on the Navy, seeing the damage to St. Louis surely must have convinced him of the intensity of the fight. Once in conversation, Foote explained that the damaged vessels had to return north for repairs before they could join in another attack, an assessment with which Grant immediately concurred. “I saw the absolute necessity of his gunboats going into hospital,” Grant recalled, but even with Foote’s expectation of returning within 10 days, Grant’s fears remained of having to undertake a lengthy siege. Foote sent word to Secretary Welles that after “consultation with General Grant . . . I shall proceed to [Cairo] with the two disabled boats, leaving the two others here . . . to make an effectual attack upon Fort Donelson.” Despite the recent failures, both men were determined to take the Confederate stronghold. The only question was whether that would happen sooner or later.21

The answer came quicker than either man would have predicted, for as they concluded their meeting, word came that the Confederates had attacked in an attempt to escape Fort Donelson. Grant’s concerns about a long siege thus proved unfounded because, as he later wrote, “the enemy relieved me of this necessity.” Upon his return to the front, Grant quickly and correctly assessed the situation, ordering his three divisions to counterattack, and while his decisiveness indicated a degree of courage and confidence, his request to the Navy for assistance suggests the depth of his concern. At about 2:00, he sent a message to the “Commanding Officer Gun Boat Flotilla,” being uncertain who was in command since Foote’s departure earlier in the day, asking that the gunboats “immediately make their appearance to the enemy. . . . Otherwise all may be defeated. . . . If the Gun Boats do not show themselves it will reassure the enemy and still further demoralize our troops.” Understanding the terrific damage the vessels suffered the previous day, Grant made clear the modest assistance he sought: “I do not expect the Gun Boats to go into action, but to make their appearance, and throw shell at long range.” Support, any support, was sorely needed.22

Grant must have wondered how responsive the Navy would be given Foote’s absence. Would Foote’s subordinates maintain the inter-Service cooperation that the two senior commanders had established over the preceding weeks, or would they leave Grant and the Army to fend for themselves, a pardonable position given the previous day’s losses? Upon receiving Grant’s request for assistance, Commander Benjamin M. Dove, now in charge of the naval element at Donelson, did not hesitate, and after quickly surveying his gunboats determined that only the St. Louis and Louisville were fit to respond. They immediately moved forward, lobbing shells into the midst of the Confederate position, marking the first time in the campaign that the two Services were simultaneously and cooperatively engaged in a fight. The effects of the naval salvos were more psychological than physical but were useful nonetheless. After the battle, Lew Wallace, Grant’s Third Division commander, recalled “the positive pleasure the sounds gave me” when the naval guns opened fire. He continued, “That opportune attack by the fleet was, I thought, and yet think, of very great assistance. . . . It distracted the enemy’s attention.” Grant’s counterattack, aided by Dove’s timely arrival and the diversion his gunners created, drove the Confederates back into Fort Donelson, where, recognizing the futility of continued resistance, they surrendered the following day. While “Unconditional Surrender Grant” received most of the credit, this was indeed a victory of effective joint operations.23

In just 10 days, the Army and Navy, thanks primarily to the close collaboration of their respective commanders, had captured two forts and shattered the Confederates’ defensive line on which they had entrusted their Western strategy. The Tennessee and Cumberland rivers now lay open to further exploitation by Union forces, an opportunity both Grant and Foote pursued, culminating in the capture of Nashville on February 25, 1862, the first Confederate state capital to fall to Federal forces.

Mutual Respect and Professionalism

The occupation of Nashville marked the successful conclusion of the campaign, and also the last time Grant and Foote worked directly with one another. They had been together for a relatively brief time, from the fall of 1861 to March 1862, and from the start, Foote was committed to developing a collaborative relationship with Grant and the Army. The naval commander was 16 years older than Grant, a difference in age and perspective that brought greater maturity and appreciation for the effectiveness and necessity of joint operations. Recognizing that personal relations mattered, Foote demonstrated professionalism and respect from the war’s beginning, always being liberal with his praise for the Army. In the days after the victory at Fort Donelson, Foote wrote that the “army has behaved gloriously,” that they “fought like tigers,” and of his relationship with Grant and Union division commander Charles F. Smith, he believed “we are all friendly as brothers.” Responding to news of Grant’s promotion at the campaign’s conclusion, Foote congratulated the new major general with the affirmation that “you have placed your name so high on the pages of your country’s history.” Grant conveyed a reciprocal sentiment, telling Foote “you are appreciated, deservedly, by the people . . . of this broad country.”24

Grant had come to admire Foote, a likeminded warrior who, despite some significant differences in personality and command style, shared a desire to maintain momentum and the initiative, a belief in unity of effort and the efficacy of joint operations, and a commitment to the Union cause. Their personal relationship, along with Foote’s experience and professional wisdom, likely helped Grant grow and mature as a commander. Foote’s firm but fair criticism of Grant’s failure to communicate at Belmont taught the young general the value and necessity of open communication, along with consideration and respect for peers, including those in the Navy. From that experience Grant left behind a dismissiveness toward the Navy—or, perhaps more accurately, he found an appreciation for the resources and capabilities the sea Service could contribute to a campaign’s success. The experiences of Grant and Foote remind us that in an era when there was no joint doctrine, effective inter-Service cooperation and effectiveness depended on mutual respect and professional interpersonal relationships. Today, despite libraries of joint manuals, publications, and doctrine, the same still holds true. JFQ

Notes

1 Timothy B. Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee: The 1862 Battles for Forts Henry and Donelson (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016), 392.

2 Milan N. Vego, “Major Joint/Combined Operations,” Joint Force Quarterly 48 (1st Quarter 2008), 113.

3 Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, January 2017), A-2.

4 Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000), 86–87; Report of Brigadier-General Grant, September 6, 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion [ORN] (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), ser. 1, 22:317. Editor’s note: All titles for ORN entries have been shortened for this article.

5 For examples of general communications, see Grant to Andrew Foote, September 22, 1861, ORN, ser. 1, 22:345; Foote to Grant, September 23, 1861, ORN, ser. 1, 22:346; Grant to Foote, October 1, 1861, in The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant [PUSG], ed. John Y. Simon, vol. 3, October 1, 1861–January 7, 1862 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967–2005), 5; Grant to Henry Walke, October 6 and 7, 1861, PUSG 3:22, 27; Walke to Grant, October 18, 1861, PUSG 3:55–56n; Grant to Walke, October 31, 1861, PUSG 3:99–100. For the exchange relating to the wharf boat, see the exchange of letters, October 17 through November 2, 1861, PUSG 3:46–48n2, 62n; Foote to Gideon Welles, October 23, 1861, ORN ser. 1, 22:376.

6 For examples of Grant and Walke’s communications, see Grant to Walke, October 6, 7, 9, 22, 1861, ORN 22:362–363, 365, 376; Grant to Walke, November 7, 1861, ORN 22:402; Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes, Jr., The Battle of Belmont: Grant Strikes South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 48–49.

7 Report of Walke, November 9, 1861, ORN 22:400–401; Report of Brigadier General Grant, November 17, 1861, ORN 22:405; Henry Walke, “The Gun-Boats at Belmont and Fort Henry,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, ed. Robert U. Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, vol. 1, The Opening Battles (New York: Century Company, 1887–1888), 361.

8 Report of Foote, November 9, 1861, ORN 2:399–400.

9 Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee, 35.

10 Report of Foote, November 9, 1861, ORN 2:400.

11 For examples, see Grant to Walke, November 15, 1861; Grant to Foote, December 13, 1861; Grant to Foote, January 2, 1862; Foote to Welles, January 9, 1862, ORN 22:431, 461–462, 482, 489; Grant to Foote, January 9, 1862, in War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), ser. 1, 7:541. Grant also supported naval operations, for example, by ordering out the cavalry to screen a reconnaissance by three gunboats down the Mississippi River toward Columbus, Missouri; see Grant to Brigadier General Eleazer A. Paine, January 6, 1862, PUSG 3:377.

12 Foote, “Notes on the Life of Admiral Foote,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 1:347.

13 Charles F. Smith to John A. Rawlins, January 22, 1862, PUSG, vol. 4, January 8–March 31, 1862, 91n; Grant to Mary Grant, January 23, 1862, PUSG 4:96; Ulysses S. Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, ed. Mary D. McFeely and William S. McFeely (New York: Library of America, 1990), 190; Grant to Henry Halleck, January 28, 1862, PUSG 4:99; Foote to Henry Halleck, January 28, 1862, ORN 22:524; Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee, 137–140.

14 Report of Foote, February 7, 1862, ORN 22:538; Grant to Captain J.C. Kelton, February 6, 1862, PUSG 4:157; Walke, “The Gun-Boats,” 367.

15. Grant to Walke, February 7, 1862, PUSG 4:168–169; Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, 197; Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee, 137–138.

16 Grant to Foote, February 10, 1862, PUSG 4:182; Lewis Wallace, “The Capture of Fort Donelson,” in Battles and Leaders, 1:412; Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee, 137–138.

17 Halleck to Brigadier General G.W. Cullum, February 9 and 10, 1862, ORN 22:577–578; Halleck to Foote, February 11, 1862, ORN 22:582; Foote to Lieutenant S.L. Phelps, February 10, 1862, ORN 22:583; Foote to Welles, February 11, 1862, ORN 22:550.

18 Grant to Walke, February 13, 1862, PUSG 4:202; Walke to Foote, February 15, 1862, PUSG 4:202–203n; Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee, 177–178.

19 Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, 202; Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee, 244–254.

20 Report of Foote, February 15, 1862, ORN 22:585–586; Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, 202–203.

21 Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, 203; Report of Foote, ORN 22:586.

22 Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, 204; Grant to Commanding Officer, February 15, 1862, PUSG 4:214.

23 Benjamin M. Dove to Foote, February 16, 1862, ORN 22:588–589; Testimony of Major-General L. Wallace, ORN 22:589–590; Smith, Grant Invades Tennessee, 330–331; Bruce Catton, Grant Moves South, 1861–1863 (New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1960), 168.

24 Foote to Welles, February 17, 1862, ORN 22:584; Foote to Caroline A. Foote, February 18, 1862, in James M. Hoppin, Life of Andrew Hull Foote, Rear Admiral United States Navy (New York: Harper and Bros., 1874), 230–231; Foote to Grant, March 8, 1862, ORN 22:660; Grant to Foote, March 3, 1862, PUSG 4:314. Writing in the 1870s, William T. Sherman remembered the old Navy commander “as full of enthusiasm and adventure as a young man,” who was “the subject of universal praise, especially by the army that saw and appreciated the gallantry of his conduct, and its important bearing on the campaign.” See Hoppin, Life of Andrew Hull Foote, 390.

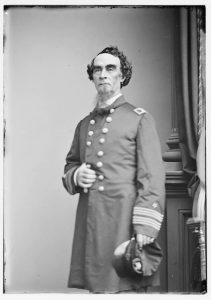

General U.S. Grant, ca. 1855–1865 (Library of Congress/Brady-Handy)