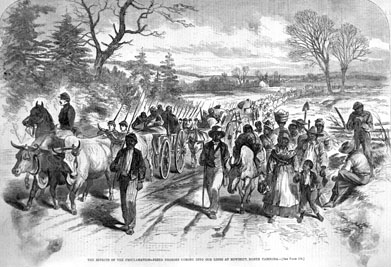

“The Effects of The Proclamation — Freed Negroes coming into Our Lines at Newbern, North Carolina.” Harper’s Weekly | North Carolina State Archives

On the night of Dec. 31, 1862, or “Freedom’s Eve” both free and enslaved African Americans waited for news from Washington, D.C. At midnight, as the new year came in, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, freeing all enslaved persons in the Confederate States. Army Soldiers traveled to plantations across the South to liberate the enslaved population. Celebrations erupted across the country as the news spread, but the message did not reach everyone. It took over two years for word of emancipation to reach Texas. On June 19, 1865, Union troops arrived at Galveston, Texas and celebrations erupted in Black communities as the news of their freedom spread. The widespread jubilation of the end of slavery in the South created a new holiday to commemorate the liberation and new independence of Black Americans.

Though the United States won its freedom from Britain during the Revolutionary War, not every American experienced that liberty. Slavery remained entrenched throughout the new country. As the nation grew, so did sentiments to end the practice across the union. Abolitionist movements, active even before the Revolution, continued into the early 19th century. Activists such as Fredrick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth pushed to end slavery and extend rights to free Black Americans. Yet, their efforts fell short, and the controversy over slavery continued to grow ultimately leading to the Civil War.

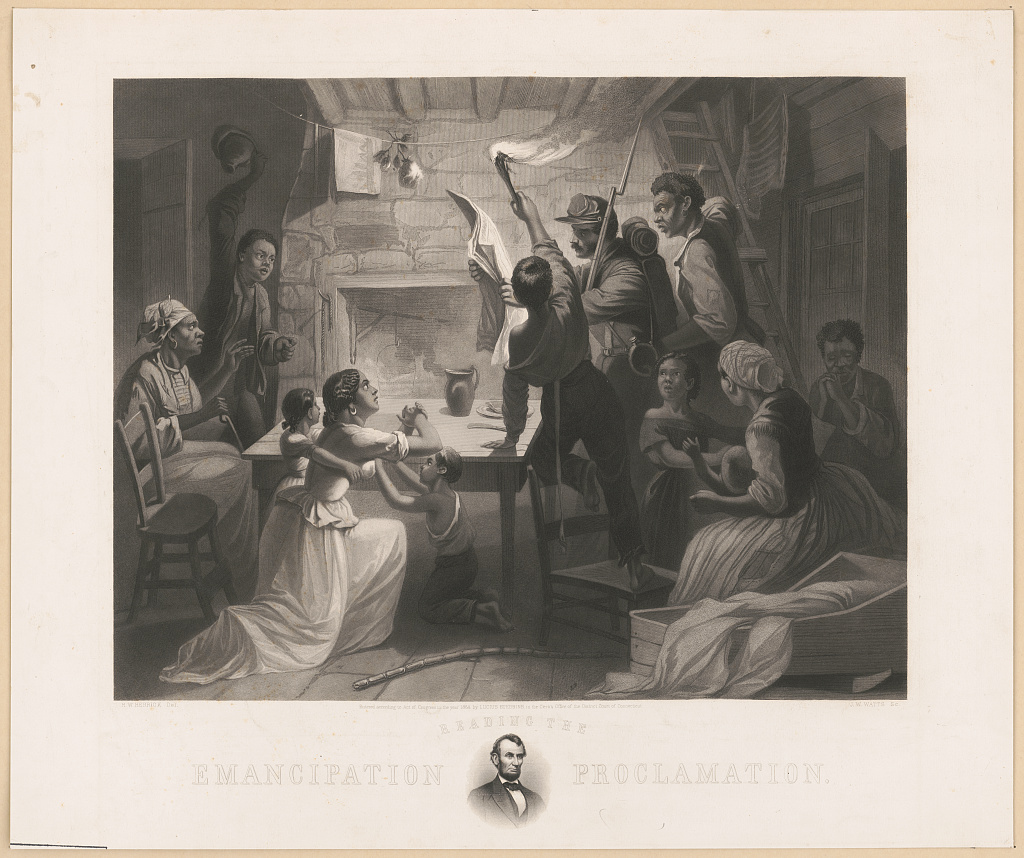

Initially, leaders in Congress and President Abraham Lincoln did not want to address ending enslavement during the war. However, Black Americans believed that Union victory meant the end of slavery. Politicians in Washington thought that the issue of slavery could be solved through legislation but wanted to win the war before addressing it. As the war dragged on, this became impossible. Though they were denied official entry into the Army, Black men still found their way to the battlefield to fight for freedom. Lincoln eventually decided to free enslaved individuals in the South and allow Black men to serve in uniform. After the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862. The proclamation went into effect on Jan. 1, 1863, and ended slavery throughout Confederate territory. Soon after, the Army began forming segregated units of Black Soldiers who served honorably throughout the war. The new units were organized as the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and states throughout the Union began forming regiments. By the end of the war, Black Soldiers made up 10% of the Army.

An Army Soldier reads the Emancipation Proclamation to a group of formerly enslaved persons. This print accompanied a pamphlet published by Lucius Stebbins detailing the Emancipation Proclamation in 1864. Library of Congress

Jan. 1, 1863, marked a day of celebration around the country as Soldiers began liberating enslaved persons in occupied enemy territory. However, most of the South was still under Confederate control and, without Union Soldiers in the area to enforce emancipation, slavery continued in those areas. Though some news reached plantations in Texas, local officials ignored them and continued the oppressive system. In most of the South, slavery continued until the U.S. Army captured an area and enforced the Emancipation Proclamation. Despite the legal blow Lincoln dealt to slavery, it took another two years to eliminate the practice throughout the country.

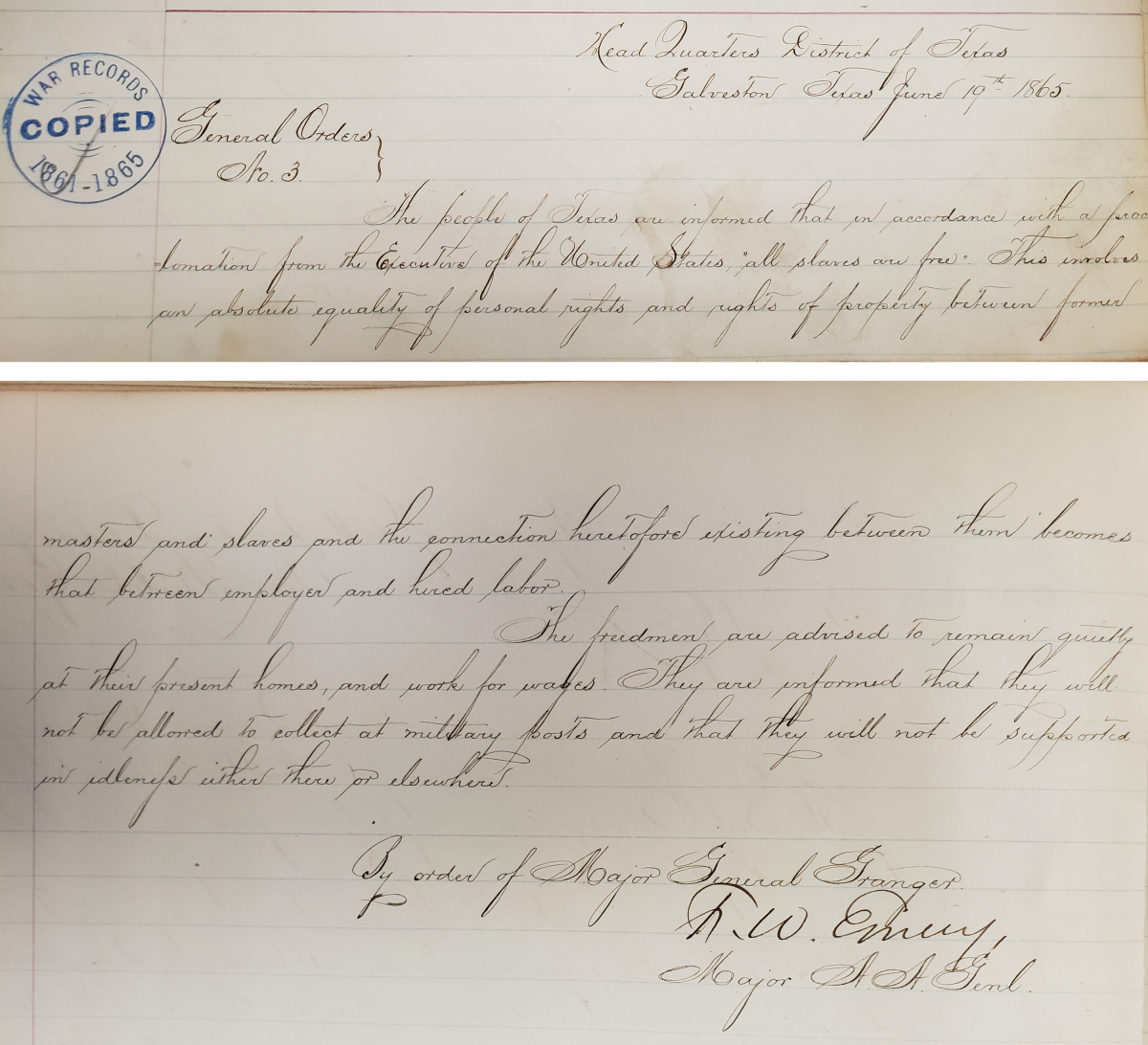

By May 1865, hostilities had mostly ceased. The Union forces’ primary mission was to occupy the South to enforce compliance and bring the states back into the Union. On Jun. 19, 1865, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger arrived with roughly 2,000 troops in Galveston, Texas, many of whom were Black Soldiers in the USCT. Though his main goal was to finally bring an end to the Civil War and welcome Texas back to the Union, he also brought freedom to roughly 250,000 enslaved persons across the state. That day, Granger issued General Order No. 3 that read,

“The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.”

Shock and euphoria spread through the crowd as the enslaved community realized their freedom was a reality. That night, celebrations erupted across Texas as the news spread across the state.

The original order given by Maj. Gen. Granger on June 19, 1865. After giving this order, all enslaved persons were now free in the Confederacy. National Archives

As news of freedom spread among Black communities in the South, so did the idea of leaving plantations and former enslavers behind for a better life. However, it took several years for many who wanted to leave to make the journey. Though many stayed longer than they wanted, the newly freed men and women created a better life for themselves in Texas. They created safe and productive communities and found new jobs to provide for their families. In addition, they created a new holiday to celebrate the freedom they finally gained on June 19. Though many Americans saw the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation as the ending of slavery in the United States, Black communities in Texas viewed it as the day Granger came to Galveston and read General Order No. 3.

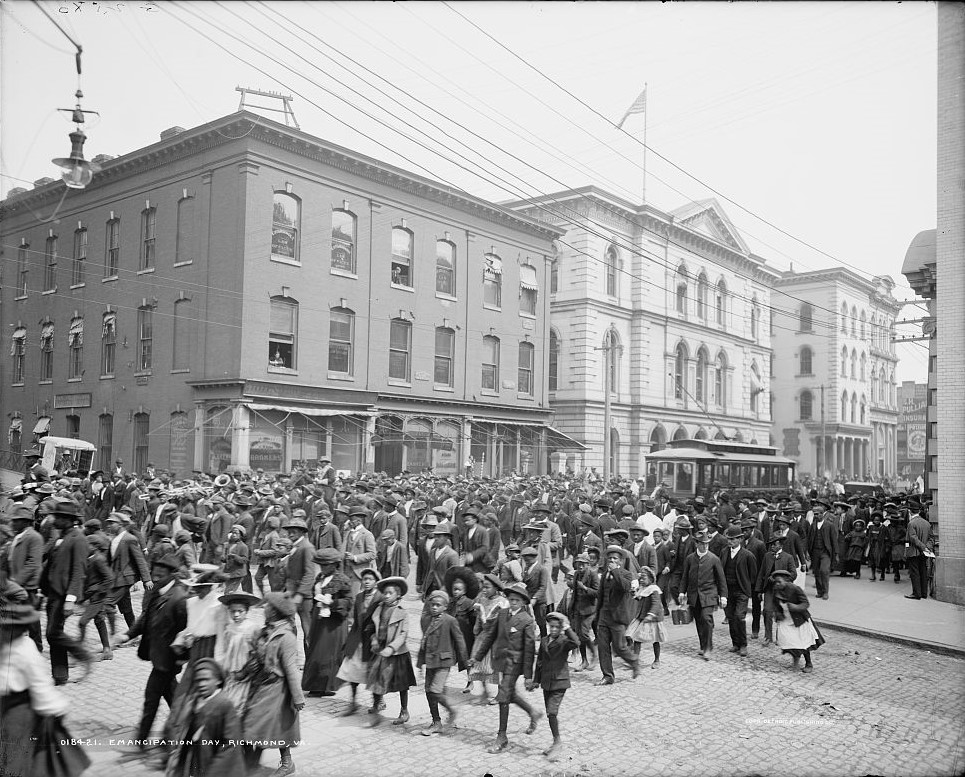

One year later, on June 19, 1866, Black Texans commemorated the end of slavery. The first Juneteenth celebrations were scattered and mostly community organized. Families of freedmen and women celebrated with food, activities, and readings of the Emancipation Proclamation or General Order No. 3. By 1867, the state capital hosted official celebrations, with other smaller celebrations taking place in communities throughout the state. Over time, news of the holiday spread as Black Americans migrated to other parts of the county. Upon moving to new areas, they celebrated Juneteenth and introduced other Black families to the holiday. Juneteenth commemorated the end of slavery but also became an important way for families to reunite and celebrate their own history as Black Americans.

Emanciaption Day celebration in Austin, Texas on June 19, 1900. Austin History Center, Austin Public Library

As Juneteenth grew and spread across the U.S., so did the celebration that accompanied it. Focus shifted from the end of slavery to the celebration of Black rights. Celebrations hosted guest speakers and read literature to further promote racial equality in the country. By the 1920s, Juneteenth was celebrated in Black communities across America and was an important social event. Department stores even ran advertisements for new clothing to buy to wear on Juneteenth. Celebrations include everything from rodeos and baseball to fishing and barbeques.

Emancipation Day parade in Richmond, Virginia, circa 1905. Library of Congress

Though Juneteenth grew and spread after the Civil War, the rise of segregation laws during the early 20th century caused celebrations to decline. Starting in the 1890s, rules began appearing across the South segregating spaces based on race called “Jim Crow Laws.” These rules were put in place to suppress the improvements made by Black Americans and physically separate them from everyone else. Conditions only worsened during the Great Depression as fewer opportunities for work were available and race became a key factor in the hiring process. This competition only served to increase the tensions between Black and white communities. The outbreak of World War II, however, provided an opportunity to face evil on two fronts. Black Americans launched the “Double V” campaign to promote not only ending tyranny in Europe and Japan but also the segregation at home. Though Black Soldiers still served in segregated units, their service and sacrifice on the battlefield began to erode race barriers leading to the official integration of military units in 1948.

Though Black Soldiers defeated tyranny overseas and in the armed forces, winning at home was an even harder struggle. Juneteenth rose in popularity across the nation in the 1950s and 60s with the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Black communities adopted the traditions of past celebrations and continued to expand on them. During this resurgence, many Black Americans began viewing Juneteenth as a second day of independence and pushed to make it a national holiday. Many Black communities didn’t view July 4th as a celebration of their freedom, and Juneteenth provided an opportunity to celebrate the end of slavery and newly gained civil rights protections during the 1960s. Texas was the first state to officially recognize Juneteenth as a holiday starting in 1972. With this breakthrough, more states began adopting Juneteenth as an official holiday. Juneteenth has continued to grow with the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in the 21st century. Finally, on June 17, 2021, Juneteenth became a federal holiday with the signing of the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act. As Maya Green of the U.S. Army put it, “For the Army, Juneteenth honors Black Soldiers that fought and sacrificed to ensure the Constitution’s promise to all Americans no matter their color, race or ethnicity … The Army’s role in liberating enslaved persons throughout the Confederacy as one of its core legacies will never be forgotten.”

Anthony Eley

Education Specialist

Sources

Anderson, Susan. “The History of Juneteenth.” California Historical Society. June 18, 2020. https://californiahistoricalsociety.org/blog/the-history-of-juneteenth/

Galveston Historical Society. “Juneteenth and General Order No. 3.” Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.galvestonhistory.org/news/juneteenth-and-general-order-no-3

Green, Maya. “Celebrating America’s ‘Second’ Independence Day: Juneteenth.” U.S. Army, June 16, 2023. https://www.army.mil/article/267641/celebrating_americas_second_independence_day_juneteenth.

Juneteenth.com. “History of Juneteenth.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.juneteenth.com/history.htm

Khan Academy. “Life after slavery for African Americans.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/civil-war-era/reconstruction/a/life-after-slavery

National Museum of African American History and Culture. “The Historical Legacy of Juneteenth.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/historical-legacy-juneteenth.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. “The Jim Crow South.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://americanexperience.si.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/The-Jim-Crow-South.pdf

Additional Resources

The Long Road to Freedom: The U.S. Army and Juneteenth

Chang, Alisa and Green, CeLillianne. “The History Of Juneteenth, And Why It Is Relevant Today.” NPR. June 19, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/06/19/880964181/the-history-of-juneteenth-and-why-it-is-relevant-today

Davis, Michael. “National Archives Safeguards Original ‘Juneteenth’ General Order.” National Archives. June 19, 2020. https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/juneteenth-original-document

Gates Jr., Henry L. “What is Juneteenth?” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/what-is-juneteenth/

Huddleston, Tom Jr. “Juneteenth: The 155-year-old Holiday’s History Explained.” CNBC. June 15, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/15/what-is-juneteenth-holidays-history-explained.html

National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Celebrating Juneteenth.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/celebrating-juneteenth

PBS. “Jim Crow South.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/freedom-riders-jim-crow-laws/

Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture. “Juneteenth: A Celebration of Freedom, Part 1.” February 23, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fkI5ricZGLQ&list=PL183D6EFEE0FCD7B0&index=3&ab_channel=PVAMU

Texas State Historical Association. “Juneteenth.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/juneteenth

Texas State Library and Archive Collection. “First Push for African American Rights.” n.d. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.tsl.texas.gov/lobbyexhibits/struggles-african