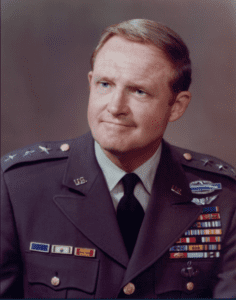

Harold G. Moore, Jr.

Lieutenant General

Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel

February 13, 1922 – February 10, 2017

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore, 1975. U.S. Army

Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore stood for the highest ideals of command, character, and compassion. During the first major battle of the Vietnam War at Ia Drang, Moore led a badly outnumbered 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment. He and his troops prevailed through the skillful use of helicopter mobility, strategic bombing, and Moore’s refusal to give up. Before the battle, Moore made a vow to his troops: “I’ll always be the first person on the battlefield, my boots will be the first boots on it, and I’ll be the last person off. I’ll never leave a body.” Moore used this same devotion to develop and champion officer training that provided Soldiers additional education and opportunities for rank advancement. These programs led to the implementation of the all-volunteer military after Vietnam.

Born in 1922 in rural Kentucky, Harold Gregory “Hal” Moore, Jr. was the oldest of four brothers. Neither of Moore’s parents completed high school. Though they were not wealthy, they were determined to provide educational opportunities for their children. Moore attended Catholic parochial schools and had an excellent academic record. Moore’s father suggested he seek an appointment to the Military Academy at West Point, but Moore needed a recommendation from a U.S. Congressman to gain admittance. Moore’s father helped him obtain a job at the Senate book warehouse in Washington, D.C. so that he could have proximity to the representatives who nominate West Point applicants. After two years of meetings and interviews, Rep. Eugene Cox of Georgia agreed to grant Moore a nomination to West Point.

Moore reported to West Point in July 1942. The United States’ entry into World War II only six months prior had created a need for officers to guide draftees and volunteers, so the Academy shortened its required curriculum to three years of training. Moore found military training both challenging and enjoyable. However, he considered the classes an “academic trip from Hell” as he struggled with math and science. Moore later joked, “I graduated at the top … of the bottom fifteen percent of my class.”

By the time Moore graduated from West Point, World War II was coming to a close. He began his career in the Philippines but soon departed for Japan, where he volunteered for duty in the 11th Airborne Division. Moore was sent back to the United States where he tested experimental parachutes and became convinced of the value of rapid troop mobility in battlefield success.

Moore’s service in the Korean War shaped his battlefield strategies. By June 1952, the war in Korea had become a WWI-style conflict with trench warfare and little success for either side. Moore was assigned to the 17th Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division, where he commanded rifle and heavy-mortar companies. Moore experienced the human wave tactics of the Chinese Red Army, infamous for sending the infantry forward through an artillery screen, resulting in an enormous loss of life. The atmosphere of constant danger tested Moore’s leadership ability, but the Army selected him for early promotion to major due to his actions on the Peninsula.

Moore’s following assignments returned him first to West Point as an instructor and then, in 1956, to the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he developed airborne and air assault equipment. Eventually, he received the call to command the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry as a lieutenant colonel. Moore’s air cavalry command was experimental. His troops were testing different approaches to control travel time, fuel consumption, weight capacity, and accurately timed artillery strikes to reduce the likelihood of going through their own artillery screen — a factor that had distressed Moore in Korea.

In 1965, Washington policymakers were concerned about the deteriorating political and military situation in South Vietnam. They determined that only American boots on the ground could reverse this precarious situation. Army planners were not ready for the immediate troop needs. Due to the non-commitment by the White House, the 1st Cavalry Division, a unique unit with a highly skilled cadre of specialists, lost men who couldn’t be replaced easily. As a result, Moore did not have a full-strength battalion while serving as a brigade commander in Vietnam. This was only the beginning of the increasing difficulties that Moore encountered during his Vietnam service.

A crucial test began when Moore received orders from Gen. William Westmoreland to “seek and destroy” enemy units responsible for attacking the Plei Mei special forces camp. Intelligence placed the enemy units in the Ia Drang Valley. There, the enemy could select the battleground while subjecting American troops to an unfamiliar and hostile terrain. On Nov. 14, the battle commenced. Moore’s 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment began an air assault and within hours of landing, the battalion became engulfed in “fighting as fierce as any ever experienced by American troops.” Because of his troops’ peril, Moore was surprised by an astonishing message: “General William Westmoreland’s headquarters wanted me to leave X-Ray early the next morning for Saigon to brief him and his staff on the battle. I could not believe I was being ordered out before the battle ended!” Moore sent his regrets to Westmoreland and stayed with his men. Moore’s unit held off waves of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) assaults for three days. For the Cavalry, the deadliest phase of the battle came on the fourth day. Only an avalanche of shells, bombs, and bullets caused the NVA to break off action against their American enemies.

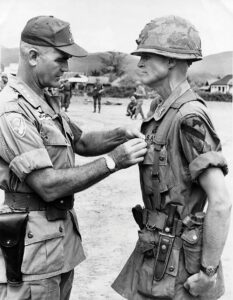

Moore’s expertise in using the helicopter to move Soldiers and supplies quickly over unfamiliar terrain surprised the NVA. For his bold leadership and courage under fire during the Battle of Ia Drang, Moore received the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second-highest award for valor. In his book, “We Are Soldiers Still: A Journey Back to the Battlefields of Vietnam,” Moore reflected on the lost lives of the young men under his command and the futility of America’s combat role in Vietnam: “We were soldiers, and we followed their orders. In times and places like this, where the reasons for war are lacking, soldiers fight and die for each other.”

Gen. William Westmoreland, left, awards Moore the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Ia Drang. U. S. Army.

After Vietnam, Moore was promoted to brigadier general and assigned to the Eighth Army in South Korea. Moore focused on finding and rewarding talent. He established a Non-Commissioned Officer Leadership School to rebuild the NCO corps depleted by the Vietnam War. He began an Equal Opportunity Policy to prohibit discrimination based on race, ethnicity, or creed. In the early 1970s, Moore served as commanding general of the Army Training Center at Fort Ord, California. He experimented with improvements to basic and advanced training procedures as the Army transitioned to the Modern Volunteer Army. His final assignments continued these innovations with personnel, recruiting, and the reduction of forces after the end of the Vietnam War. He retired in August 1977, after 32 years of service.

Throughout his military career, Moore’s family, especially his wife, was a constant comfort and support. Moore met and married Julie Compton in 1948. Julie grew up in a military household and was familiar with the challenges of moving from post to post. Together, Moore and Julie forged an unstoppable team united in military service.

Julie Moore volunteers for Red Cross in Korea. U. S. Army

Julie was born in 1929 and followed her father, Army Col. Louis J. Compton, from post to post during his military career. She was used to the small tract houses on an Army post, the lack of air conditioning in hot weather, and the scramble for suitable housing as families moved unexpectedly. Once married, she helped change the methods used to report battle deaths to Army families and increased support for the wives and children who moved with each new deployment. In 2005, the Ben Franklin Global Forum established the Julia Compton Moore Award for service to the United States Army by a civilian spouse: “Mrs. Moore’s actions to change Pentagon death notification policy in the aftermath of the historic battle of the Ia Drang Valley represents a significant contribution to our nation … It serves today as a shining example of one of Mrs. Moore’s many contributions to the morale and welfare of the Army family.”

Julie Moore died on April 21, 2004. Hal described his wife as his greatest friend and partner: “A soldier needs his mate. My wife was every inch a soldier as I was.” Hal Moore died in 2017, at 94 years of age. Hal and Julie Moore were buried in the Old Post Cemetery at Fort Benning, Georgia. In May 2023, the Army renamed Fort Benning to honor the Moores. It is the first time the Army has named a base in honor of a married couple. According to Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, “The renaming of this installation as Fort Moore is a fitting tribute to their lifelong dedication to the Army and its soldiers and their families.”

Fort Moore leaders along with members of the Moore family unveil the official Fort Moore sign during a redesignation ceremony May 11, 2023 held at the post’s historic Doughboy Stadium. U.S. Army; Patrick Albright

Caitlin Healy

Education Specialist

Eugene Ramsey Hardin IV

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

“Ben Franklin Global Forum to Announce Establishment of Julia Compton Moore Award (Press Release).” Business Wire. Gale Cengage Learning, June 9, 2005. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0EIN/is_2005_June_9/ai_n13805658.

Daddis, Gregory A. Westmoreland’s War: Reassessing American Strategy in Vietnam. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Dickstein, Cory. “When Fort Benning Becomes Fort Moore, It Will ‘Honor the Army Family.’” Stars and Stripes, February 22, 2023. https://www.stripes.com/branches/army/2023-02-22/fort-benning-confederates-fort-moore-9219684.html.

Galloway, Joseph L. “Hal Moore Biography.” Landing Zone X-Ray: The Battle that Changed the War in Vietnam,” October 1, 2023. https://www.lzxray.com/hal-moore-biography/.

Guardia, Mike. Hal Moore: A Life in Pictures. Maple Grove, MN: Magnum Books, 2018.

Halberstam, David. The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. New York, NY: Hyperion, 2007.

Hastings, Max. Vietnam, An Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2018.

Hennigan, W. J. “At Last, The U.S. Military Won’t Have Bases Named After Confederates.” Time. Time, INC, May 24, 2022. https://time.com/6180832/military-bases-remove-confederate-names-history/.

“Julia Compton Moore Obituary.” Columbus (Georgia) Ledger-Enquirer. April 21, 2004. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/ledger-enquirer/name/julia-moore-obituary?id=29850286.

Kingseed, Cole C. “Team of Two: Moores Recognized for Exceptional Service.” AUSA, February 22, 2023. https://www.ausa.org/articles/team-two-moores-recognized-exceptional-service

Moore, Harold G., and Joseph L. Galloway. We Are Soldiers Still: A Journey Back to the Battlefields of Vietnam. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 2009.

Moore, Harold G., and Joseph L. Galloway. We Were Soldiers Once … and Young: Ia Drang, the Battle that Changed the War in Vietnam. Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 2008.

Roberts, Sam. “Lt. Gen. Harold Moore, Whose Vietnam Heroism Was Depicted in Film, Dies at 94.” New York Times. February 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/13/us/harold-moore-dead-general-author-we-were-soldiers-once.html.

Sorley, Lewis. Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.

“Vietnam War Hero Hal Moore Dies at Age 94.” U. S. Army, February 16, 2017. https://www.army.mil/article/182389/vietnam_war_hero_hal_moore_dies_at_age_94.

Wright, James Edward. Enduring Vietnam: An American Generation and Its War. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2020.

Additional Resources

The Official Home Page of the United States Army. https://www.army.mil/article/182389/vietnam_war_hero_hal_moore_dies_at_age_94

A Tribute to LTG Hal Moore. https://youtu.be/w00HolLYnGI?si=8W4ZmMbfggdmiPX_

A New Look at Ia Drang. https://www.historynet.com/new-look-ia-drang/?f

Hal Moore Interview at LZ X-Ray. November 16, 1965. https://youtu.be/70zHanLhce0?si=OY-mhMvSK7vEIMOI

The Vietnam War Lesson Guide. https://edsitement.neh.gov/vietnam-war-lesson-guide