Reflecting attitudes of the day, segregation and racial barriers pervaded the U.S. Army during World War II. Even so, in 1944, a group of Black infantry Soldiers gained entrance to the Army’s elite Airborne School. After graduating from the grueling course, they faced continued racial prejudice in the Army and society. Since most of the first graduates came from the 92nd Infantry Division “Buffalo Soldiers,” this new organization became the “Triple Nickles,” after the Buffalo Nickle. This new unit became a pioneer in airborne operations, from firefighting to atomic warfare. As the Army pushed Black Soldiers to menial jobs, the Triple Nickles became the first Black parachute infantry battalion and found a welcoming home in the airborne community. After the war, they made the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 82d Airborne Division the first integrated combat unit.

Pathfinding

The story of the Triple Nickles began both in Washington, D.C.’s halls of power and the red clay of Fort Benning, Georgia. In Washington, pressure to admit Black Soldiers into front-line and elite units grew until it demanded action. Finally, in April 1943, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the formation of an all-Black paratrooper unit. At Fort Benning, the all-Black Parachute School Service Company had a serious morale problem. While paratrooper students trained to join the Army’s elite and fight in World War II, the service company guarded Airborne School after training hours with no hope for front-line action. To build a sense of unit pride, 1st Sgt. Walter Morris began to train his company like Airborne School students. Seeing an opportunity, the commandant of the Airborne School, Gen. Ridgely Gaither, offered Morris a position as a first sergeant in a new, all-Black paratrooper unit. Morris accepted, then helped Gaither hand-pick 19 Soldiers for a test platoon. These college graduates and elite athletes, with their proven character and intellect, set out to prove Black Soldiers could be paratroopers.

1st Sgt. Walter Morris undergoes jumpmaster personnel inspection prior to his first jump. U.S. Army

Training

Airborne School was a grueling course divided into four one-week phases. While in the course every individual, regardless of rank, was treated as a private. The first week, “A Stage” was a physical gauntlet of almost constant running and calisthenics. It was designed to wash out those without the mental toughness to endure while teaching fundamental skills. Even athletes in peak physical condition felt the physical strain of proving they were tough enough to be paratroopers. “B Stage” continued the exercise while drilling landing fundamentals and basic hand-to-hand combat. While “A” and “B” stages tested physical and mental endurance, “C Stage” challenged courage. During “C Stage” paratroopers simulated the exiting and in-descent portions of a parachute jump. Both were, and still are, generally considered more mentally challenging than actually jumping. Finally, during “D Stage,” aspiring paratroopers made their five qualifying jumps to earn their jump wings. Oddly enough, it was this grueling crucible which gave Black Soldiers respite from discrimination. During training they were paratrooper students, nothing more or less, regardless of their instructors’ backgrounds or views on race.

On February 18, 1944, 16 enlisted Soldiers from the test platoon graduated as the first Black paratroopers. A week later Carstell Stewart graduated as part of the first integrated airborne training platoon. Shortly after the test class, six Black officers graduated from Airborne School on March 4, 1944. Once they had earned their jump wings, in the words of then-2nd Lt. Bradley Biggs, “something of a brotherhood [among paratroopers across racial lines] developed whereby we worked together to train incoming members, we came to share experiences in the field, we ate together, and on occasion, we taught together.” Despite continued segregation and racism in the Army, Black paratroopers found a home in the airborne community.

Organization and Expansion

The first two classes of Black paratroopers became cadre for the 555th Parachute Infantry Company at Camp Mackall, North Carolina. This company of 165 then went through extensive training, making them one of the best fighting elements available and ready for war. With Airborne School opened to Black Soldiers, the 555th grew to a battalion ready to reinforce paratroopers on the Western Front. Given the heavy losses among paratroopers in the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 16, 1944, the Army needed replacements. The German counter-offensive proved the mettle of Black Soldiers even though the Army normally kept them away from the front line. Racial prejudice in Washington slowed the process of sending Black combat units to the European Theater until April 1945. By then, German forces were crumbling, and a new threat was emerging in the Pacific Northwest.

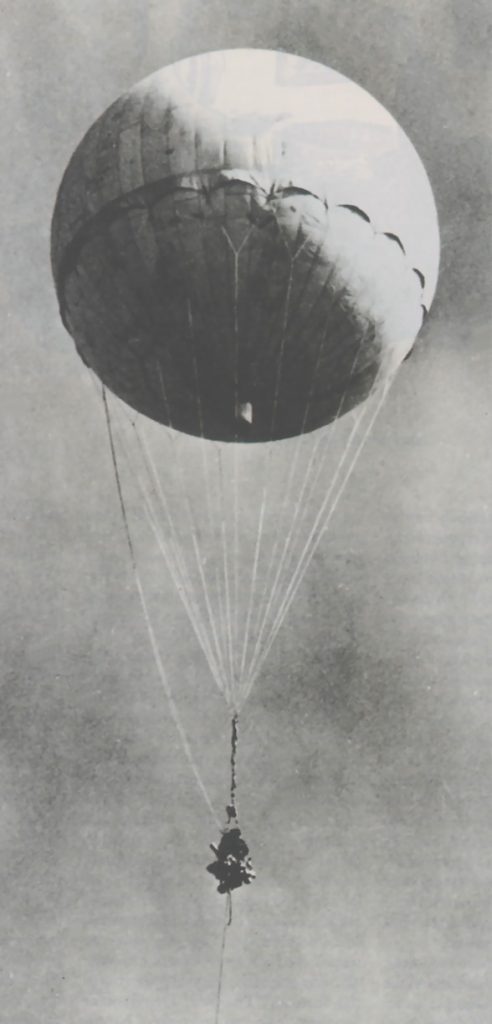

Terror-Bombing by Balloon

After the Doolittle Raid on Japan’s Home Islands, Japan’s military searched for a weapon to reach the mainland United States. By hanging incendiary bombs on balloons and floating them on the jet stream, Japanese bombs could reach America. These bombs had the potential to disrupt infrastructure and incite terror on the West Coast, with one balloon making it as far as Michigan. Another balloon cut power lines and disrupted plutonium production for the Manhattan Project. A third incinerated a reverend’s wife and part of a Sunday School class as they picnicked near Gearhart Mountain, Oregon. The Army suppressed news of the bombs to prevent a panic, but the U.S. Forest Service needed help.

Japanese incendiary balloon bomb. U.S. Army

Smoke Jumpers in Operation Firefly

In May 1945, the 555th Battalion departed for Pendleton, Oregon and Chico, California, to combat forest fires ignited by these Japanese bombs. Combat-ready paratroopers traded their rifles and rucksacks for fire-fighting gear for “Operation Firefly.” During the summer and fall of 1945, the Triple Nickles fought fires and disarmed bombs throughout the Pacific Northwest. They earned the nickname “Smoke Jumpers” due to their ability to insert fire-fighting teams by parachute. In doing so, they helped to innovate and codify the tactics, techniques, and procedures for parachuting into forest fires. Already familiar with using explosives, the Triple Nickles became explosive ordnance disposal experts.

After jumping into a fire the Triple Nickles often remained on the ground for days at a time. In proud paratrooper fashion, their supplies only consisted of what they jumped in with. The smokejumpers contained fires until Forest Service mule trains arrived with more firefighters. Each detachment then packed up their gear, walked back to base, and prepared for the next jump. The Triple Nickles’ excellence in both firefighting and bomb disposal won over the Forestry Service. Despite their discipline and the support of the Forestry Service, the 555th still faced discrimination from the Pendleton Air Base commander. The Triple Nickles’ professionalism and positive attitude won over the residents of the town. They also became ambassadors for the airborne community to sister services. The 555th tested using Navy planes to deploy paratroopers as reinforcements during mock enemy attack. In all, the Triple Nickles made around 1,200 jumps to help control 36 fires and dispose of several bombs.

Spearhead of Integration

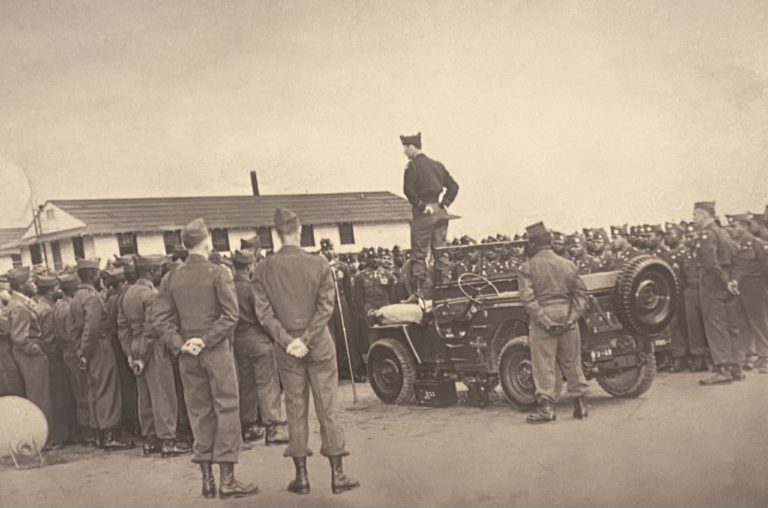

Following the end of World War II, the Triple Nickles returned to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Upon arrival, the battalion received the worst housing on the post at the whim of a prejudiced garrison commander. This abuse and the “two-color army” which kept these elite Soldiers separate frustrated Maj. Gen. James Gavin. As commander of the 82d Airborne Division, he campaigned to integrate the 555th into the 82d Airborne. Facing continued resistance, Gavin guaranteed the Pentagon that paratroopers of the 555th would earn the right to wear the honors won by the Division in World War II “by their high standards as Soldiers.” Gavin got his way, and the 555th marched down Fifth Avenue in New York City as part of the World War II victory parade. While Gavin had the moral compass and influence to force the issue of integration, it was the spotless record and reputation for discipline and expertise the Triple Nickles had created for themselves which made the move possible. Gavin always sought the absolute best Soldiers for his units and the Triple Nickles had shown they were among that elite company.

Gen. Gavin formally welcomes the Triple Nickles to the 82d Airborne. U.S. Army Airborne & Special Operations Museum

The 555th’s demonstrated flexibility and ability to adapt to new techniques proved invaluable to Gavin. As the Army looked at operations in the atomic age its brightest minds tried to find a way to succeed in an atomic ground war. Gavin believed dispersion and paratrooper-like mobility were the keys to surviving and winning. Dispersion, though, required a willingness to change the operations process based on the environment. Not only did the Triple Nickles adapt to the new way of doing business, they became the exemplar of the infantry battalion in the atomic age. Because of the unit’s success, it represented the Army in inter-service training operations. After becoming so valuable to the Army, Gavin decided the 555th had more than earned integration into an infantry regiment.

Gavin selected his old unit to become the first integrated infantry regiment. When the 555th deactivated on December 15, 1947, its personnel became 3d Battalion, 505th Airborne Infantry. High performers from the old 555th moved into leadership roles in companies throughout the regiment. In short order, members of the Triple Nickles won the respect of the entire 82d Airborne and earned key positions throughout the division. As Walter Morris, a member of that first test platoon recalled: “White soldiers and black soldiers moved into the same barracks. . .That was historic. . .And there was not one incident of racism—not one.” When President Harry S. Truman desegregated the Army on July 26, 1948 the 82d saw no change, a tribute to the Triple Nickles’ excellence.

Legacy

The impact of the Triple Nickles extended far beyond their actions in World War II. Several Triple Nickles formed the core of the Second Ranger Company and won glory making the Ranger Regiment’s first combat jump at Musan-Ni during the Korean War. As the 82d Airborne desegregated, the Triple Nickles’ quality broke stereotypes about Black Soldiers. The experience of Soldiers weakened prejudicial barriers in the civilian world. In 2004, sixty years after he had secured his jump wings and made history, Walter Morris pinned those wings onto his grandson. After sixty years of breaking down barriers and driving integration by dint of his exemplary service, Morris was the guest speaker. By then, integrated classes and graduations were normal because Morris and his fellow Soldiers had become the best the Army had to offer. The 555th’s “Triple Nickles” paved the way not only for Black Soldiers in the elite forces of the Army, but for a positive wave of change in race relations throughout the United States after World War II.

Jonathan Curran

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

555th Parachute Infantry Association. “Official Site Of 555th Parachute Infantry ‘Triple Nickle.’” 555th Parachute Infantry. 2008. http://www.triplenickle.com.

Biggs, Bradley. The Triple Nickles: America’s First All-Black Paratroop Unit. Hamden: Archon Books, 1986.

Booth, T. Michael, and Duncan Spencer. Paratrooper: The Life of Gen. James M. Gavin. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Briscoe, Charles H. “The 2nd Ranger Infantry Company: ‘Buffaloes’ in Korea, 29 December 1950—19 May, 1951.” Veritas 6, no. 2 (2010): 22-33.

Posey, Edward L. The US Army’s First, Last, and Only All-Black Rangers: The 2d Ranger Infantry Company (Airborne) in the Korean War, 1950-1951. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009.

Queen, Jennifer. “The Triple Nickles: A 75-Year Legacy.” Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 28, 2020.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/features/triple-nickles-75-year-legacy.

Stone, Tanya Lee. Courage has No Color: The True Story of the Triple Nickles, America’s First Black Paratroopers. Somerville: Candlewick Press, 2013.

Wyden, Ron. Recognizing the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion. S. 3206. 115th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 163, no. 91 (May 25, 2017): S. 3206-3207.