George B. McClellan

Major General

United States Army, Army of the Potomac

December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885

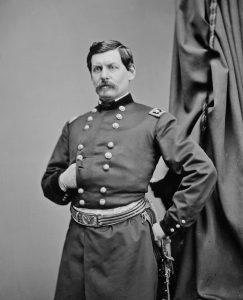

George B. McClellan by Mathew Brady, 1861. Public Domain.

Thousands of generals served in the U.S. Army during the American Civil War, but few provoke controversy like Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. A career Army officer and later a politician, he served during the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. While commanding the Army of the Potomac, McClellan engaged Confederate forces in several major battles. Through triumph and failure, McClellan’s service in the Army during the Civil War contributed to Union victory, though his legacy is still debated by historians.

Born on December 3, 1826, to a prominent Philadelphia family, George Brinton McClellan enjoyed a privileged upbringing. Initially planning to enter medicine or law, the University of Pennsylvania accepted him into preparatory school at 14 years old. Instead, McClellan decided to enter military service two years later. He attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, the academy having waived the minimum age requirement to allow McClellan to attend at the request of his influential father. He graduated second in his class and began his military career as a second lieutenant in 1846.

Serving in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, McClellan deployed as an engineering officer after the outbreak of the Mexican-American War in April 1846. After fighting in the battles of Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec, he was promoted to brevet captain for his skill and bravery under fire. Following the war, McClellan returned to West Point to train cadets in engineering. He also participated in several engineering projects, such as mapping waterways and surveying for railroads. In March 1855, the Army reassigned him to the 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment.

Army leadership recognized McClellan’s talents, despite his tendency to complain about his peers. They selected him as an official American observer of the Crimean War in the fall of 1855 to observe innovations in technology and warfare. After returning to the United States, McClellan published a manual on cavalry tactics, including a saddle design that the Army adopted and used for decades. Despite his success, McClellan resigned from the Army on January 16, 1857, and entered the railroad industry, becoming president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad by 1860. He married Mary Ellen Marcy, on May 22, 1860.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, northern civilian leaders encouraged McClellan to re-enter federal military service. Due to his experience and abilities, the Army appointed him a major general on May 14, 1861. Working with Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, the Army’s general-in-chief, the two formed what became known as the Anaconda Plan. The plan called for the blockade of Confederate waterways to slowly deprive the enemy of supplies. On the battlefield, McClellan defeated Confederate forces at the Battle of Philippi, Virginia, which earned him the nickname, “The Young Napoleon.” After the Union Army’s defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, President Abraham Lincoln gave him command of all federal forces in Northern Virginia.

Lincoln tasked McClellan with creating an Army that could end the rebellion and protect Washington, D.C. The young general created the Army of the Potomac and built over 40 forts to defend the nation’s capital. The Army of the Potomac grew from 50,000 troops to over 168,000 in just five months, making it the largest army to ever take the field in North America. Loved by his men, McClellan inspired his Soldiers and improved morale. On November 1, 1861, he became general-in-chief of all U.S. armies.

McClellan’s many qualities, such as his skills in organization and logistics, were often undone by his arrogance and cautiousness. He frequently clashed with Lincoln, privately calling him “nothing more than a well-meaning baboon.” Lincoln, frustrated by McClellan’s reluctance to attack the rebel forces in Virginia, remarked to another officer, “If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time.” Despite his cautious nature, McClellan engaged the enemy in the Seven Days Battles in the spring of 1862 outside of Richmond, Virginia. His forces defeated Robert E. Lee’s outnumbered Confederate forces at the Battle of Malvern Hill, but McClellan decided to retreat rather than continue the fight.

Disappointed with McClellan, Lincoln turned to Maj. Gen. John Pope to lead a new command, the Army of Virginia. After Pope’s defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run, he was removed. McClellan and his Army of the Potomac once again became the Union’s primary field force in Virginia. He led the Army of the Potomac against Lee’s forces again at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. Despite stiff enemy resistance, he defeated Lee’s rebel army, causing them to retreat from Maryland. This victory allowed Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, granting freedom to enslaved people in Confederate territory. However, Lincoln grew frustrated when McClellan failed to destroy the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia as they retreated. Lincoln relieved him of command on November 5, 1862.

McClellan was reassigned to Rhode Island and given no new tasks. Though popular with his men, some in the North criticized McClellan for his conduct in battle, arguing that he was an ineffective general. In 1864, McClellan ran as a Democrat in a failed presidential campaign against Lincoln. After the war, McClellan worked on engineering and railroad projects around the country. He became governor of New Jersey in 1876, serving a single term. McClellan always defended his conduct during the war, arguing that it was the Lincoln administration’s fault he was not more successful. He died on October 29, 1885 of a heart attack. Many historians, both past and present, heavily criticized McClellan’s conduct. However, some recent historians believe that McClellan was treated unfairly. Regardless of controversy, McClellan served the Army for decades and undoubtedly contributed to Union victory in the Civil War through his creation of the Army of the Potomac and victory at the Battle of Antietam.

A.J. Orlikoff

Lead Education Specialist

Sources

“George B. McClellan.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/george-b-mcclellan.

Grimsley, Mark. “The Lincoln-McClellan Relationship in Myth and Memory.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association (University of Illinois Press) 38, no. 2 (2017): 63-81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26290255.

Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

“George Brinton McClellan: From Peninsula to Maryland, McClellan’s role in the summer of 1862.” National Parks Service. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/people/george-brinton-mcclellan.htm.

Rowland, Thomas. George B. McClellan and Civil War History: In the Shadow of Grant and Sherman. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1998.

Sears, Stephen W. George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon. New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1988.

Additional Resources

“Antietam: Animated Battle Map.” American Battlefield Trust. June 27, 2019. Video, 15:31. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8ybkoGmHww&ab_channel=AmericanBattlefieldTrust.

Library of Congress. “George Brinton McClellan Papers.” https://www.loc.gov/collections/george-brinton-mcclellan-papers/about-this-collection/.

McClellan, George B. The Life, Campaigns, and Public Services of General McClellan (George B. McClellan): Hero of Western Virginia! South Mountain! And Antietam!. Philadelphia: T.B. Peterson and Brothers, 1864. https://books.google.com/books?id=99caPGVgXDYC&pg=PA15#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Perry, Warren. “A New Man in Charge: George B. McClellan (Part 1): Fooled by the Guns at Munson’s Hill.” Facetoface (blog). https://npg.si.edu/blog/new-man-charge-george-b-mcclellan-part-1.